Ending Impunity in Syria: International Prosecutions and the Challenge of Pursuing Justice

Michael Volk

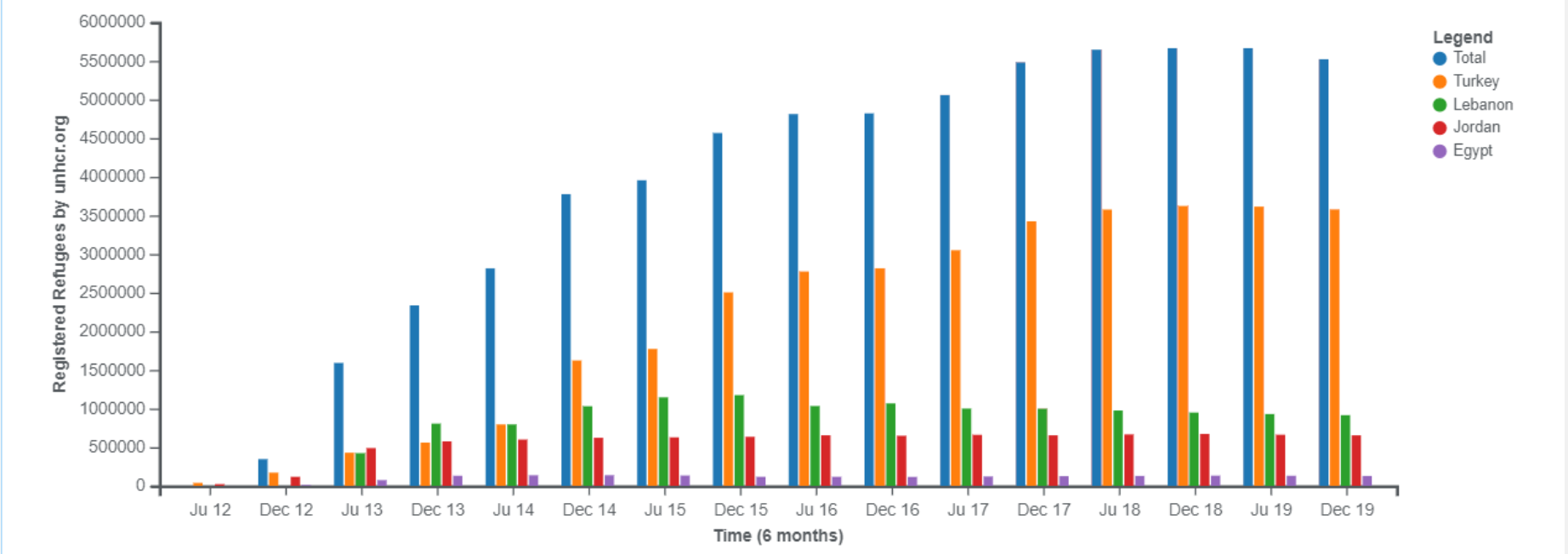

In 2011 peaceful protests began in Syria against the authoritarian regime of Bashar al-Assad. These protests have mutated into brutal war, and years of relentless fighting have battered the Syrian people, the economy, and the entire country. The fallout, as Aljazeera has described it, has resulted in “the worst refugee crisis in 20 years.”[1] The Syrian Observatory on Human Rights reports that, as of March 2018, over half a million people have been killed as a result of the civil war in Syria.[2] According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the fighting has displaced 6.6 million Syrians internally and another 5.6 million more around the world.[3] Atrocities against the civilian population, including chemical weapons attacks beginning in 2013, have largely been perpetrated by the Assad regime.[4]

As of the writing of this paper, the violence continues, and the conflict grows ever more complex. A comprehensive account of how the war has evolved or what might happen going forward is beyond the scope of this paper. Many factors have contributed to the evolution of the current situation, including “long-standing political, religious, and social ideological disputes; economic dislocations from both global and regional factors; and worsening environmental conditions.”[5] This paper will consider major factors which led to, induced, and amplified the violence; identify crimes perpetrated by the Assad regime; and analyze national and international legal responses, geopolitical implications, and structural challenges to pursuing transformative justice for Syrian victims.

Influence of Drought and Climate Change

An alarming trend toward persistent, multi-season droughts has drastically limited Syrians’ access to water. Syria is naturally a water-scarce region, receiving, on average, less than 250 mm of rainfall annually.[6] Starting in 2006 and lasting into 2011, Syria experienced a relentless period of extreme drought that contributed to agricultural failures, economic dislocations, and population displacement.[7] This prolonged drought has continued and is now being described as the “worst long-term drought and most severe set of crop failures since agricultural civilizations began in the Fertile Crescent many millennia ago.” [8]

A 2010 study compiled evidence showing “statistically significant increases in evaporative water demand in the eastern Mediterranean region between 1988 and 2006, driven by apparent increases in sea surface temperatures.”[9] Further, a 2012 study suggested that “climate change is already beginning to influence droughts in the area by reducing winter rainfall and increasing evapotranspiration.” [10]

Scientists are not alone in their warning of the potential impacts of climate change. The U.S. Department of Defense reported that “climate change could have significant geopolitical impacts around the world, contributing to poverty, environmental degradation, and the further weakening of fragile governments. Climate change will contribute to food and water scarcity, will increase the spread of disease, and may spur or exacerbate mass migration.” [11] Additionally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change wrote in 2014 that there was “justifiable common concern” that climate change increased the risk of armed conflict in certain circumstances. [12]

Persistent drought caused major crop failures, killed livestock, drove up food prices, sickened children, and the resulting economic hardship led to pervasive collapse of rural communities, forcing 1.5 million rural residents into Syria’s overcrowded cities.[13] In turn, the already unstable urban environment devolved, furthering food shortages, unemployment and economic hardships, and social turmoil. Observers expressed concerns as early as 2008 that the resulting population displacements “could act as a multiplier on social and economic pressures already at play and undermine stability in Syria.” [14]

The UN estimated that by late 2011 between two million and three million people were affected, with a million people driven into food insecurity.[15] The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) conducted agricultural and food assessments in 2011 and 2012, which showed increasing poverty and food insecurity, identified three million people in “urgent need” of food assistance, and concluded that “agricultural water use is unsustainable.” [16]

Displacement, Refugee Welfare, and Impact on Host Nations

These early warnings proved to be prophetic when political unrest began building around the town of Deraa, which saw a particularly large influx of people displaced by crop failures. [17] The regime failed to implement measures to alleviate the effects of drought, and this was “a critical driver in propelling . . . massive mobilizations of dissent.”[18]

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Antonio Guterres said that this displacement is the largest refugee crisis since the genocide in Rwanda, reporting a “level of human suffering . . . without parallel” in anything he had previously witnessed. [19] He warned that “if it goes on, and on, and on like it has been in past few months, it risks becoming the worst refugee crisis since the Second World War.” [20]

As of December 2013, Syrian refugees comprised twenty-five percent of the population in Lebanon; the equivalent in the United States would be an influx of fifty-six million refugees.[21] Jordan and Iraq made similar efforts to accept Syrians, and Turkey has spent billions of dollars supporting Syrian refugees. [22] This massive increase in population in these neighboring countries has caused enormous problems in Iraq, a country already faced with violence and civil unrest, and in Jordan, a country lacking access to water. [23] “So indeed,” said Guterres, “this is becoming a regional crisis, a crisis that risks an explosion in the Middle East . . ..” [24]

According to UNHCR, more than half of the then-2.2 million registered Syrian refugees were children, and 80% of those children in Lebanon, and 56% in Jordan, do not have access to schools. [25] Displaced parents are largely unable to provide for their families’ basic needs, so child labor and forced prostitution of boys and girls became exceedingly common. [26] Guterres said, “As the war goes on, as those that are in exile for a longer and longer period and have exhausted their resources, the situation will get worse. Their needs will increase, and the capacity to respond will not be able to match those increasing needs. [27]

Many, if not all, of the displaced children were traumatized by the violence they experienced in Syria and various host countries. A report from UNHCR said, “[t]he scars of the children appear as a loss of speech, broken sleep, challenging behavior, and many are becoming angry at their plight, which is dangerous for the region.” [28]

Unrest, Oppression, Brutality, and Uprising

Within the broader context of environmental, economic, social, and political factors, as well as the increasing influence of the Arab Spring, the people of Dara’a were primed to resist the oppressive brutality of the Assad regime, and the rest of the country rapidly followed suit. In Dara’a, four boys were detained after painting anti-government sentiments on a school building. When their fathers inquired as to their well-being, Assad’s security forces bluntly replie,: “Forget those children. Go home and make some more. If you can’t manage, send us your women and we’ll make more for you.”[29] The community, incensed by the officials’ cruel remarks, took to the streets to demand that the boys be released. Although the demonstrations were initially peaceful, the police quickly increased their use of force from setting up barricades, to spraying people with tear gas and water cannons, until ultimately a helicopter opened fire on the civilians, killing two men.[30]

Unrest continued to grow while Assad’s security forces killed more civilians each day, which increasingly drew more people from surrounding villages to Daraa to join the protest.[32] The boys were released after 45 days, and upon seeing their battered faces, it was immediately clear to the protestors that government officials had tortured them.[33] The resulting outrage fueled further and more agitated protests, and after declaring a breach of public order, officials again opened fire on the people.[34] This time, however, video footage of security forces indiscriminately killing civilians spread rapidly via the internet, and protests soon erupted in major cities throughout Syria.[35]

What started as civil unrest had very rapidly become an uprising. Violence has completely devastated Daraa, but there is still a community attempting to maintain some semblance of normality. Women were oppressed under the regime, so many gladly stepped into important new roles such as civil defense trainers teaching children vital survival techniques; internet activists and community organizers; and teachers using whatever material they could recover from bombed-out state schools. [36] Meanwhile, street protests continue amid all the fighting, but across the city on both sides of the divide, everyone wants peace. [37]

Crimes Perpetrated by Assad’s Regime

Assad’s army consistently used extreme force against civilians living in territory that it did not control, regardless of participation or affiliation with rebel forces. As a show of force, the army regularly killed anyone seen on the street, shot into individual homes, and dropped bombs on residential communities.[38] The army says it uses “smart weapons” and “surgical strikes,” but in reality the army routinely and indiscriminately bombs residential areas. [39]

Organized regime effort to arrest, torture, and kill civilians:

Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) has uncovered and analyzed documents proving that Assad’s regime systematically tortured and killed civilians in state detention centers. [40] Those detained were relief and aid workers, journalists, activists, and peaceful demonstrators, but the government officially charged all of them as terrorists in an attempt to document the killing of these civilians with bureaucratic justifications to cover their crimes against future allegations. [41]

Thousands of photographs documenting detainees being tortured and killed were leaked to the international media.[42] Mohammad al-Abdallah, director of SJAC, said, “[t]he photos clearly indicate that torture was not an isolated incident perpetrated on an individual scale, but was rather a state policy based on organized efforts to arrest, torture, and kill people.”[43] In August 2016, Amnesty International issues a report documenting the death of 17,723 people between March 2011 and December 2015. The report cited “horrific stories of torture varying from boiling with water?? to beating to death,” and documented how the regime secretly hanged 50 to 100 people each week. [44]

Chemical weapons attacks against civilian population:

A report detailing epidemiological findings of major chemical attacks in the Syrian war presents compelling evidence of civilian targeting. The report states that civilians comprised 97.6% of direct deaths from chemical weapons attacks in Syria, while combatants comprised only 2.4% of direct deaths.[46] Tragically, children made up a significant percentage of those civilian deaths; comprising 13%–14% of direct deaths in the three major chemical attacks occurring in 2013, 21% in 2016, and 34.8% in 2017.[47]

These findings show that the Assad regime’s major chemical weapons attacks were indiscriminate, and the disparity between civilian and combatant deaths suggests that they targeted civilians directly. Both are violations of International Humanitarian Law.[48]

Attacks on journalists and aid workers:

The presence of foreign journalists in opposition areas makes a regime nervous. In 2012, Marie Colvin, Paul Conroy, and Remi Ochlik were reporting on the Syrian regime. Colvin and Ochlik were killed and Conroy was wounded, targeted by regime forces. [49] Legal action in the US District Court for the District of Columbia charged the Assad Regime with arranging Colvin’s death, and the Court found the Syrian government liable and awarded $302 million in damages.[50] Judge Jackson said that Assad “intended to intimidate journalists” and cited the regime’s “long-standing policy of violence” and the regime’s labeling of journalists as terrorists and “enemies of the state.” [51] Colvin’s family saw the verdict as an opportunity to raise awareness about the regime’s crimes and to build the case for future international action.[52]

International Legal Responses and Efforts Toward Justice

Structural and geopolitical aspects of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) pose a significant obstacle to the international community’s ability to respond to the Assad regime’s crimes. Syria has not ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, so, according to Human Rights Watch, the ICC could only obtain jurisdiction by UN Security Council referral.[53] But, given Russian permanent veto power and its long-standing support of the Assad regime, the UNSC is unlikely to make such a referral or to establish an international tribunal to adjudicate crimes committed in Syria.[54]

However, there is an investigatory body: the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (IICI), created in 2011, an international mechanism examining alleged violations of international human rights law.[55] In 2013, UN Human Rights Chief Navi Pillay said that the IICI has “produced massive evidence [of] very serious crimes, war crimes, crimes against humanity” and that “the evidence indicates responsibility at the highest level of government, including the head of state.”[56] The IICI has repeatedly accused the Syrian government, with support from Russia and Iran, of crimes against humanity and war crimes, and has also accused rebel groups of committing war crimes. [57]

The International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) was created by the United Nations in February 2017 to circumvent the Security Council’s inability to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC, and according to Catherine Marchi-Uhel, head of the IIIM, it “also represents an opportunity to address some weaknesses in the existing international criminal law framework.”[58] The IIIH has collected over a million records documenting abuses committed since 2011, and their collection grows rapidly. [59] The documents described atrocities committed by all parties to the Syrian conflict, including forced disappearances, sexual harassment and assault, torture and execution, and targeting vital centers such as schools and hospitals.[60]

IIIM has received 23 requests for support from war crimes units and national judiciaries, “and the rate of such requests is expected to increase going forward.”[61] Trial International, an NGO dedicated to fighting impunity for international crimes, provides a timeline of legal efforts to hold perpetrators accountable. Beginning in September 2011, the German Federal Prosecutor opened investigations into war crimes and crimes against humanity in Syria, which has so far conducted investigations against at least 10 individuals involved in crimes perpetrated by the Regime. [62] On March 1. 2017, a group of international organizations and Syrian victims filed a complaint alleging torture and further filed complaints in November of 2017 denouncing crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in regime detention facilities. [63] On June 8, 2017, the German Court issued an arrest warrant against Jamil Hassan for crimes against humanity and war crimes, accusing Hassan of having killed, tortured, and caused severe physical or mental harm to numerous detainees between 2011 and 2013. [64] Additionally, in October 2018, French authorities issued an international arrest warrant against Hasan as well as Ali Mamluk and Abdel Salam Mahmoud, accusing all three of complicity in acts of torture, forced disappearances, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.[65]

Recently, the US Congress considered legislation, originally introduced in March of 2017, that would allow “sanctions against the Assad regime, Russia, and Iran for past and ongoing war crimes in Syria.”[66] If approved by Congress, this bill, H.R. 1677, “would extend sanctions to several major sectors of Syria’s state-driven economy and to any government or private entity that aids Syria’s military or contributes to the reconstruction of Syria.”[67] The bill would not create a legal mechanism to open lawsuits or establish courts, but it would contribute to achieving some justice for victims and to sending a message that the US will no longer ignore the perpetration of such crimes. It passed in the House in January 2019 but S 52, the companion bill in the Senate, has not come to a vote.

Conclusion

The international community’s hands are partially bound by existing structural and geopolitical factors, which means that ending impunity in Syria will require countries that have not previously exercised international involvement to step up to the challenge. National judicial actions, such as the German and French efforts described above, must continue until a more direct venue is available, but alone they will not be able to accomplish the level of criminal adjudication that this tragedy warrants. And, considering the analysis indicating that climate change will continue exacerbating displacement, food insecurity, unemployment, and political instability; the need for effective international institutions and cooperation will only increase in the coming years.[68]

Pursuing justice for the victims of atrocities committed throughout the Syrian war will require significant changes in the current balance of international relations. The ICC cannot serve as the venue for legal action on Syria without structural changes to the UNSC or a change in the alliance between Russia and Assad. Universal jurisdiction allows proceedings to occur in many countries, and this can continue. In addition, a country could bring charges against Syria at the International Court of Justice.

[1] Aljazeera, “UN: Evidence Links Assad to Syria War Crimes.” 2 Dec. 2013, www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2013/12/un-evidence-links-assad-syria-war-crimes-2013122181457135

[2] “World Report 2019: Rights Trends in Syria.” Human Rights Watch, 23 Jan. 2019, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/syria

[3] Id.

[4] “Remarks by the President in Address to the Nation on Syria.” Whitehouse.Gov, Whitehouse, 11 Sept. 2013, obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/09/10/remarks-president-address-nation-syria

[5] Gleick, Peter. “Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria: Weather, Climate, and Society: Vol 6, No 3.” Ametsoc.Org, 2014, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1

[6] Ametsoc.Org, 2014, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] “Pubs.GISS: Romanou et Al. 2010: Evaporation-Precipitation Variability over the Mediterranean and the Black…” Nasa.Gov, 2010, pubs.giss.nasa.gov/abs/ro08010f.html. Accessed 16 Dec. 2019.

[10] Hoerling, M., J. Eischeid, J. Perlwitz, X. Quan, T. Zhang, and P. Pegion, 2012: On the increased frequency of Mediterranean drought. J. Climate,25, 2146–2161, doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00296.1. Google Scholar

[11] U.S. Department of Defense, 2010: Quadrennial defense review report. U.S. DOD Rep., 105 pp. 85 [Available online at http://www.defense.gov/qdr/qdr%20as%20of%2026jan10%200700.pdf.] Google Scholar

[12] Kelley, Colin P., et al. “Climate Change in the Fertile Crescent and Implications of the Recent Syrian Drought.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 112, no. 11, 2 Mar. 2015, pp. 3241–3246, www.pnas.org/content/112/11/3241, 10.1073/pnas.1421533112. Accessed 20 May 2019.

[13] Id.

[14] [14] Gleick, (2014)

[15] FAO, 2012: Syrian Arab Republic Joint Rapid Food Security Needs Assessment (JRFSNA). FAO Rep., 26 pp. 6 [Available online at http://www.fao.org/giews/english/otherpub/JRFSNA_Syrian2012.pdf.] Google Scholar

[16] Id.

[17] Gleick, (2014)

[18] Saleeby, S., cited 2012: Sowing the seeds of dissent: Economic grievances and the Syrian social contract’s unraveling. [Available online at http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/4383/sowing-the-seeds-of-dissent_economic-grievances-an.] Google Scholar

[19] Aljazeera, “UN: Evidence Links Assad to Syria War Crimes.” 2 Dec. 2013, www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2013/12/un-evidence-links-assad-syria-war-crimes-2013122181457135

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Aljazeera, “UN: Evidence Links Assad to Syria War Crimes.” 2 Dec. 2013, www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2013/12/un-evidence-links-assad-syria-war-crimes-2013122181457135

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Id.

[29] Aljazeera English. “The Boy Who Started the Syrian War | Featured Documentary.” YouTube, 10 Feb. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=njKuK3tw8PQ.

[30] Aljazeera English. “The Boy Who Started the Syrian War | Featured Documentary.”

[31] https://longform.org/posts/the-graffiti-kids-who-sparked-the-syrian-war

[32] Id.

[33] Id.

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] Aljazeera English. “The Boy Who Started the Syrian War | Featured Documentary

[39] Id.

[40] Enab Baladi. “Al-Assad’s Crimes in Millions of Documents: When Will Accountability Start? – Enab Baladi.” Enab Baladi, 3 Oct. 2018, english.enabbaladi.net/archives/2018/10/al-assads-crimes-in-millions-of-documents-when-will-accountability-start/#ixzz687ccCVqF.

[41] : Id.

[42] : Enab Baladi. “Al-Assad’s Crimes in Millions of Documents: When Will Accountability Start? (2018)

[43] : Id.

[44] : Amnesty International; Amnesty.Org, 2016, www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2017/02/amnesty-international-annual-report-201617/

[45] http://cdn.thedailybeast.com/content/dailybeast/articles/2014/07/31/syrian-defector-assad-poised-to-torture-and-murder-150-000-more/jcr:content/image.img.2000.jpg/1406821474989.cached.jpg

[46] Rodriguez-Llanes, Jose M., et al. “Epidemiological Findings of Major Chemical Attacks in the Syrian War Are Consistent with Civilian Targeting: A Short Report.” Conflict and Health, vol. 12, no. 1, 16 Apr. 2018, 10.1186/s13031-018-0150-4. https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-018-0150-4

[47] Id.

[48] Authority for International Humanitarian Law

[49] https://thearabweekly.com/syrian-regime-still-has-no-qualms-about-attacking-journalists

[50] Bowcott, Owen. “US Court Finds Assad Regime Liable for Marie Colvin’s Death in Syria.” The Guardian, The Guardian, 31 Jan. 2019, www.theguardian.com/media/2019/jan/31/us-court-finds-assad-regime-liable-marie-colvin-death-homs-syria.

[51] Id.

[52] Id.

[53] “Q&A: Syria and the International Criminal Court.” Human Rights Watch, 17 Sept. 2013, www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/17/qa-syria-and-international-criminal-court#1

[54] Enab Baladi. “Al-Assad’s Crimes in Millions of Documents: When Will Accountability Start? (2018)

[55] Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic. Ohchr.Org, 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/hrc/iicisyria/pages/independentinternationalcommission.aspx

[56] Black, Ian. “Bashar Al-Assad Implicated in Syria War Crimes, Says UN.” The Guardian, The Guardian, 2 Dec. 2013, www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/02/syrian-officials-involved-war-crimes-bashar-al-assad-un-investigators.

[57] Id.

[58] “Head of International Mechanism on Syria Describes Progress Documenting Crimes Committed by Both Sides, as General Assembly Takes Up Report | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases.” Un.Org, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/ga12139.doc.htm

[59] Id.

[60] : Enab Baladi. “Al-Assad’s Crimes in Millions of Documents: When Will Accountability Start? (2018)

[61] “Head of International Mechanism on Syria Describes Progress Documenting Crimes Committed by Both Sides, as General Assembly Takes Up Report | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases.” Un.Org, 2019

[62] Jamil Hassan – TRIAL International.” TRIAL International, 2019, trialinternational.org/latest-post/__trashed-5/.

[63] Jamil Hassan – TRIAL International; (2019)

[64] Jamil Hassan – TRIAL International; (2019)

[65] Jamil Hassan – TRIAL International; (2019)

[66] “The United States Is about to Sanction Assad, Russia and Iran for Syrian War Crimes.” The Washington Post, 11 Dec. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/12/11/united-states-is-about-sanction-assad-russia-iran-syrian-war-crimes/?utm_source=reddit.com ; H.R.1677 – 115th Congress (2017-2018): Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2018. Congress.Gov, 2017, www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1677.

[67] The United States Is about to Sanction Assad, Russia and Iran for Syrian War Crimes.” The Washington Post, 11 Dec. 2019

[68] Gleick, (2014)