The Forgotten Holocaust and

The Continued Persecution of the Romani

by Brianne Rankin

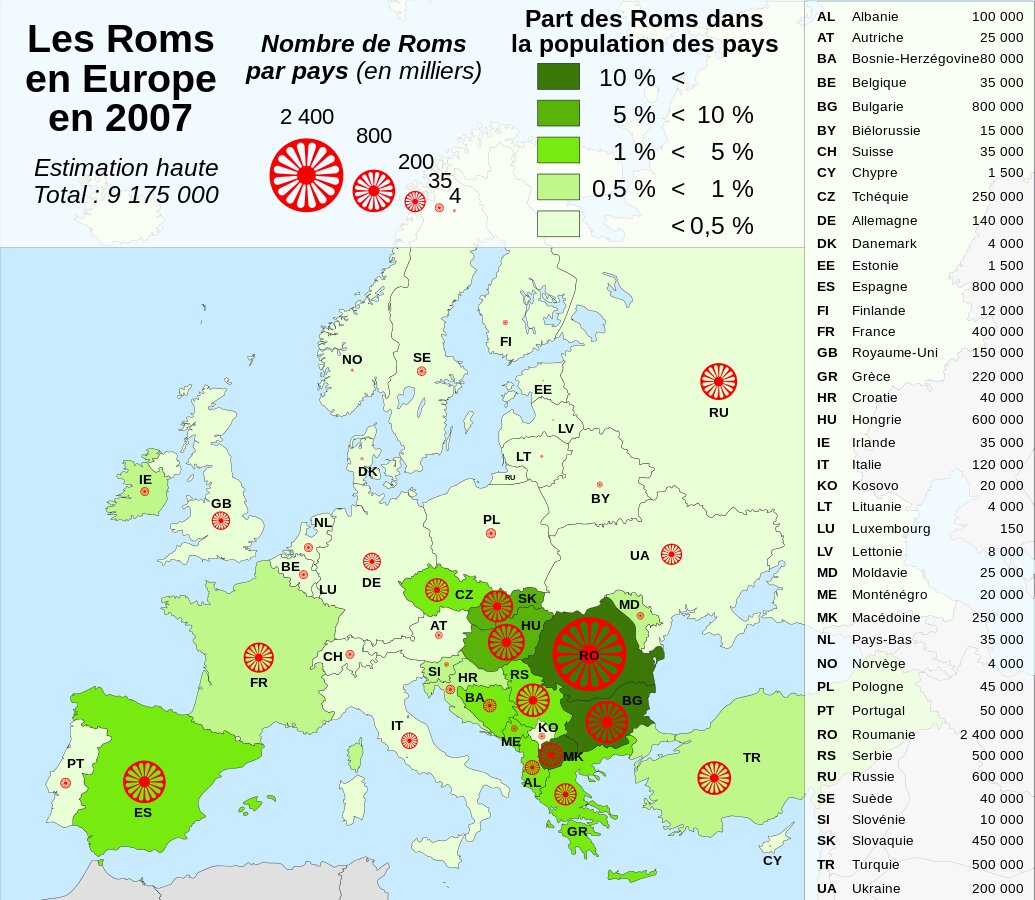

There are between ten and twelve million Roma living in Europe, making them the largest ethnic minority that region.[1] There are also nearly one million Roma in the United States and hundreds of thousands elsewhere, in Australia, Canada, Brazil, and throughout Western Asia.[2] Despite these large numbers, the Romani, often referred to as the Roma or by the derogatory term ‘Gypsies,’ are one the most misunderstood and persecuted populations in Europe. They currently face the effects of historic genocide on top of being the targets of contemporary hate crimes and discrimination.

The Romani People

Much of the misunderstanding stems from confusion and misinformation about who the Romani are, and their distinction from the other traditionally iterant populations of Europe. First there is the misconception that the Romani are Romanian. The Romani are not from the nation of Romania; they are composed of an entirely unrelated Indo-Aryan ethnic group.[3] Romanians from the nation of Romania, on the other hand, tend to be of an Eastern European Romance ethnic group. Interestingly, and more confusingly, according to the 2011 Romanian Census, approximately 3.3% of the population of Romania was Romani.[4] Another misconception is that the Roma are of ancient Roman origin.

The next misconception revolves around the term ‘Gypsy.’ While the term is considered derogatory, it is still in wide use, and it muddies the waters about who the Roma are, since the term is applied generally to any traditionally iterant group in Europe – from the Roma to the distinct ethnic and linguistic group of Scottish Travelers. There is a pervasive myth that the Roma are called ‘gypsies’ because of they came to Europe from Egypt, but recent genetic findings disprove this notion.[5] In fact, we now know that the Roma originated from a very small group that migrated to Europe from the northern Indian subcontinent. Particularly, they are from the Rajasthan, Haryana, and Punjab regions of modern-day India, and historians suggest that the group left India some 1,500 years ago.[6] So not all ‘gypsies’ are Roma – but the Romani diaspora also includes many subgroups (sometimes erroneously referred to as “tribes”) that have developed from that initial migratory group, all of whom have been labelled as gypsies at one time or another.

This in turn further confuses, because several of the subgroups do not use the term ‘Roma’ to describe themselves regardless of common origin. A perfect example of this are the Sinti, the name of the primary group of Roma in German-speaking countries. The Sinti fall under the Romani diaspora because they are from the same ethnic group as other subgroups, such as the Ashkali. The Sintis’ name for their original language is even Romanes, yet the Sinti and the Roma are often distinguished from each other as unrelated groups and the Sinti do not refer to themselves as Roma.[7] This is true for many of the Romani subgroups – they do not refer to themselves as Roma, and they identify as distinct ethnicities based in part on territorial, cultural, and dialectal differences, and self-designation; as separate from each other as any subgroup would be from the Scottish Travelers. However, for the purposes of this paper, the Roma will refer collectively to the multitude of ethnic subgroups of common origin from the Indian subcontinent.

Roma and Genocide: Two Fronts

The Roma are simultaneously suffering from the consequences of two separate issues. The first is the suffering the Roma still face due to past persecution – they are in the eighth stage of genocide, denial, after their suffering in the Holocaust. The second is the current persecution they face, which puts them in perhaps the first stage, classification, of a new genocide, in which they are the targets of hate crimes, employment discrimination, and forced migration or deportation. Their persecution will be discussed on both fronts.

Causes of Antiziganism

Before discussing the means of persecution, it is essential to examine the causes. Antiziganism, or Romaphobia, is “hostility, prejudice, discrimination, or racism that is specifically directed toward the Romani people,” and the practice, like that of antisemitism, has a history almost as old as the Roma themselves.[8] Antiziganism is slightly different from anti-gypsy sentiments, since anti-gypsy attitudes are directed toward not only the Roma but also toward other historically iterant groups, such as the Yenish in Switzerland and the Irish and Scottish Travellers. However, both antiziganism and anti-gypsyism stem from the same kinds of prejudices, and both have had, and continue to have, severe repercussions for the Roma.

Interestingly, and unlike the experience of many other persecuted groups, antiziganism is not primarily based on religious discrimination, since there are both Christian and Muslim practicing members of the Roma. The roots of the discrimination are, instead, mainly ethnic and economic.

The proximate causes, and those most obvious to the casual observer, are that the Roma are ethnically different from other Europeans, as well as the perception that the Roma don’t belong to any one nation due to their nomadic traditions. These two proximate causes are the sources of many stereotypes of the Roma: that they are uneducated, criminal, subversive, and generally they are the outcasts of society. Another factor in this is that there is little resistance to these stereotypes of general criminality, and the persecution of the Roma is often justified by calls for “law and order” and to “reduce crime.”

However, there are also the ultimate causes of the persecution, primarily the economic causes. While there has been distrust of the Roma since their arrival in Europe, the Industrial Revolution did much to devalue the work of tradesmen and craftsmen, which the Roma historically are. This compounded the difficulties for the Roma. This remains true today: the Roma tend to be employed in either seasonal or trade work, both because of many employers’ resistance to hiring them, and because of their itinerant customs. Because they often find it difficult to find steady work, they are perceived to be lazy or as drains on the economic system. When they do find work, it is in occupational areas that are perceived to have very little value, and so they continue to be perceived negatively.[9]

The Roma have also been hit relatively hard by environmental changes, and they are victims of what is called environmental racism. This is the case particularly in eastern Europe, where Cold-War-era industrial development was particularly harsh on the environment.[10] Environmental racism is “the practice of environmental injustice within a racialized context,” where social inequality and discrimination against minorities subjects vulnerable populations to disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards. Vulnerable groups also are denied access to clean air, water, and other natural resources, or there are infringements on their environmentally-related human rights.[11]

The Roma have been targets of environmental racism primarily, again, due to their migratory nature, which causes them to settle (or to be forced to settle) at the edges of cities or communities, “thus exacerbating the already marginal economic and political position of Roma in Europe, whose communities continue to subsist as internal colonies within Europe.” 11 Essentially the Roma are relegated to the undesirable locales such as dump sites or sites close to toxic waste, and the government subsequently maintains no responsibility to provide services such as sanitation, housing, or education. This perpetuates a vicious cycle: the Roma are perceived as uneducated, and therefore will not be accepted in non-Roma schools, yet the government will not establish Roma schools to the same standards (or sometimes at any standards), and so the Roma are actually often without education and unable to get work or to improve the community’s overall situation. Antiziganism is therefore both the cause and the consequence of these policies, and the discriminatory cycle continues.

Historical Violence

While the Cold War may have made the persecution of the Roma worse due to environmental concerns, the origins of this persecution date as far back as the 13th century and continued in the Middle Ages. Hatred of the Roma was prevalent across all of Europe by the 16th and 17th centuries. The Roma were often enslaved, and when they were not enslaved, they were relegated to the lowest rungs of the social ladder due to their previously-mentioned lack of a “visible permanent professional affiliation.”[12] For example, the ‘Egyptians Act of 1530’ banished all ‘Gypsies’ from England; a 1545 declaration by the Diet of Augsburg declared that killing of Roma would not be considered murder; and in 1660 King Louis XIV of France banished all Roma from the country

In the 18th century, the Holy Roman Empire stepped up the persecution to include mass hangings, floggings, and banishment, perhaps the first recorded genocide that the Roma faced.[13]

Although the scale of the violence perpetrated against the Roma is quite shocking, the most significant violence in scope was the Porajmos, translated literally as “the devouring,” the term the Roma use to describe the Holocaust, in which at least 130,565 Roma were killed. Estimates by various sources tend to be much higher, some as high as 1.5 million, but a more realistic figure generally cited is 500,000.[14]

The start for the genocide, which took place in the Third Reich from 1935 to 1945, had origins as early as 1899. In that year, Munich established its Nachrichtendienst in Bezug auf die Zigeuner, the Intelligence Service Regarding the Gypsies, which issued identification cards, prevented the Roma from using public services, and implemented general surveillance of the Roma. The Nazi party actually used a 1905 report on the ‘Gypsies’ as part of the justification for the Porajmos.[15]

The Nazi Party specifically targeted the Roma, and reports and letters written by leaders like Himmler call for the execution and extermination of the ‘Gypsies.’[16] They lost their citizenship after the passage of the infamous Nuremburg Laws, and, like the Jews and other ‘undesirables,’ were forced to wear symbols to denote their identity. Their symbolization took the form of a brown inverted triangle. The Roma faced deportation, extermination in concentration camps such as Auschwitz, and subjection to horrific medical and other experimentation.

However, the persecution of the Roma was not as geographically consistent as other persecution during the same time period. The General Governor of occupied Poland at one point refused to accept some 30,000 Roma being deported from Austria and Germany, and the deportations in France were relatively small. On the other hand, the Reich’s Einsatzgruppen mobile killing units and the Treblinka camp were much less preferential to the Roma, and atrocities were committed en masse against the Roma.[17]

Contemporary Violence

One of the serious issues concerning contemporary violence against the Roma is that, by all accounts, it is occurring constantly, yet it rarely makes the news. It is difficult to find recent news articles by reputable journalists that mention violence against the Roma, especially articles written in English. There are articles written in France that document problems, but France is identified by international watch groups as one of the less problematic countries.[18] The violence seems to be the worst in Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia, according to human rights watch groups, but there is little recognition by international news outlets of this fact through news stories or intervention. Therefore when discussing the contemporary persecution of the Roma it is important to note that one of the biggest problems is a lack of reporting or recognition, and that only the most serious or attention-grabbing instances make the news.

Another issue is that, because the Roma are dispersed throughout Europe, and often still highly mobile, they face inconsistent treatment between countries as well as between Roma subgroups such as the Sinti. This, in addition to the inconsistent reporting in various countries and the lack of reporting by victims themselves, makes for a scattered and incomplete view of the violence perpetrated against the Roma as a whole. For example, the 2018 OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) report on Bias Against Roma and Sinti lists that only 10 states report incidents of hate and violence to ODHIR, and reports were only collected as having occurred in 14 states.[19]

While the number of actual incidents reported was low, the report does give some insight into the nature of attacks that are occurring, and these attacks are primarily violence committed against people as opposed to threats or attacks against property. The report also demonstrates that reporting is on the rise, as more countries are added every year – which also gives the impression that attacks are on the rise, although this is not verified.

The 2010 Amnesty International Report on violent attacks against the Roma, although almost ten years out of date, demonstrates that violence against Roma is on the rise – or at least it was in 2010. It also reinforces the fact that the Roma are not a primary concern for many human rights organizations or reporting agencies.[20], [21] An independent UN expert has called for recognition and consequences for the rise in violence against the Roma as recently as April 8, 2019, although the source of his data for this rise is unknown.[22] However, other experts have suggested that social media and the rise in nationalism and continued calls for “law and order” have contributed to a rise in anti-Roma sentiments, including recent calls for sterilization and Roma-only censuses.[23]

However, even if reporting leaves much to be desired, there are a few trends that span most of Europe. The first is that there is still widespread educational discrimination against the Roma, and Roma children are often sent to separate schools.[24] The Romani children are often sent to ‘delinquent’ schools, or they are placed in classes for students with learning disabilities. European officials censured both the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 2007 for forcibly segregating Romani children from regular schools.[25] The historic practice of removing Roma children from their homes and communities (an early indicator of genocide) appears to have dwindled for most of the European Union, although the discrimination against the children in schools continues in full force.

Reported crimes against women are also very high for the Roma, another indicator of possible genocide, according to the 2011 report by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA).[26] While both Roma men and women fare much worse on all “core social indicators” than other Europeans, Roma women in particular lack education, are married early, suffer employment discrimination, live in extreme poverty, lack healthcare, and suffer from violence and discrimination. In particular, Roma women lack education, and many are married and have children by the time they are 18, which leads to other forms of discrimination. Violence against women solely for being Roma, according to the FRA, was experienced by as many as 13% of women in the five years before the study was conducted, and incidents of harassment were experienced by as many as 53% of those surveyed. Furthermore, while violence against men was found in slightly higher numbers, the women were much less likely to report crimes committed against them due to their ethnicity. As many as 74% of incidents of violence against women is theorized to go unreported, although exact numbers are impossible to ascertain.

Crimes Being Perpetrated

The Roma were certainly victims of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other atrocity crimes throughout history, and as recently as World War II. However, none of these are currently occurring according to the contemporary definitions, and so the sole focus of this analysis will focus on whether the Roma are currently victims of genocide.

Genocide is defined as the intention to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group.[27] Genocide can take many forms, including killing members of the group, imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group, or forcibly removing children of the group to be transferred to another group. The question that is posed, therefore, is whether the Roma are currently subject to this kind of violence. The answer is both yes and no.

The historical violence certainly presents a textbook example of genocide perpetrated against the Roma. However, this past genocide is not necessarily causing current harm, until we consider the concept that denial is the final stage of genocide. In 1996, Gregory Stanton identified the following eight stages in genocide: classification, symbolization, dehumanization, organization, polarization, preparation, extermination, and denial.[28] Under this framework, the current denial of the genocide in the 1940s means that the genocide is still occurring. Certainly, Holocaust denial is becoming more and more prevalent across Europe and the world.[29]

The current violence is not so easy to classify as genocide, because although there is violence, as the many examples above have demonstrated, and many of these violent acts are motivated by a desire to destroy the Roma in whole or in part, they are not connected enough to constitute actual genocide. However, referring back to Stanton’s stages, the Roma are certainly in the classification stage, and many of the Roma are experiencing dehumanization due to their poor living conditions as well as policies of deportation and segregation in various countries. So while the Roma are not undergoing genocide currently (except for the denial stage), they are certainly on the cusp of genocide if violence and discrimination against the Roma is not curbed by those with the power to do so.

Support and Resistance

There is little in the way of support or resistance against those perpetrating violence against the Roma, either locally, nationally, or internationally. Although there are several watch groups that have their eyes on the Roma, such as Amnesty International, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, and the United Nation Human Rights Office, which formed a regional working group concerning the Roma, none of these watch groups do more than watch and make note of policies and actions against the Roma.[30]

There is no system of humanitarian aid or assistance to the Roma on an international level. For example, although the Adventist Development and Relief Agency does include the Roma on their website, there is no description of any aid that the Roma are specifically receiving in excess of general aid after earthquakes or other natural disasters. There are also no military or diplomatic interventions, nor are there likely to be any. Individual countries in Europe cannot point the finger at each other for discrimination or violence for fear of consequences for their own policies and actions, and those outside of Europe have similar problems. Furthermore, the global track record for intervention during full-blown genocide is spotty at best, so intervention in the early stages is unlikely.

There is a slow movement toward recognizing the Roma and their historical persecution, although whether this is enough to combat denialism remains to be seen. Crimes against the Roma during World War II were officially recognized by the German authorities in 1982.[31] Thirty years later, in 2012, Chancellor Angela Merkel unveiled a memorial to the Roma (Sinti) Genocide in Berlin.[32] Today, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, and Croatia observe August 2 as Roma and Sinti Genocide Remembrance Day. On April 15, 2015, the European Parliament passed a similar resolution calling for August 2 to be recognized as European Roma Holocaust Memorial Day to commemorate the victims of the Roma genocide in World War II.[33]

Even more impressive in terms of time passed between crimes committed and apology, the Catholic Church issued an apology in 2000 to the Roma, among other victimized groups, and in 2019 Pope Francis issued a further apology and asked for further forgiveness.[34], [35]

However, even if there have been a few apologies and a handful of memorials, there have been very few attempts at restitution to the Roma since 1945. In fact, the only fund providing restitution specifically to the Roma dried up in 2006 – and the fund was set up to serve primarily the disabled, homosexuals, and Jehovah’s Witnesses and instead only ended up unintentionally paying out to the Roma.[36] After payouts of $32 million, or about $4 a day to individual survivors, the fund was exhausted, and there has not been a revival since lawsuits against Swiss banks and German companies have essentially ended.

However, as recently as 2018, there has been a renewed effort to memorialize and repay survivors through the Sinti Roma Holocaust Memorial Trust, although its primary focus is to generate museum exhibits and remembrance rather than to advocate for restitution.[37] Hopefully, activists like those behind the trust can continue to combat denial and to shine the spotlight on the plight of the Roma, both past and present.

Transitional Justice Recommendations

It is perhaps a little late for retributive justice for the Holocaust, especially as time continues to pass. However, restorative justice is still perhaps possible, and the current violence against the Roma could be addressed through implementing some measures of transitional justice as well.

Restorative justice would include restitution similar to the Claims Conference set up for Jewish Holocaust survivors, and it would be ideal if restitution would be sufficiently funded to be useful. Recognition of the violence that the group endured would also be more widespread, through museums and memorials. This would be helpful in reducing the stereotyping and misinformation and could lead to less discrimination and violence.

Possible Steps for Negative Peace

Negative peace refers to the absence of violence. When a ceasefire is enacted, for example, a negative peace will ensue.[38] It is negative because something undesirable stopped happening (e.g. the violence stopped, the oppression ended). The Roma, for the most part, have still not attained negative peace in most of the world, particularly in Europe. The persecution needs to end immediately for negative peace to be achieved. The Human Rights First report on the Roma recommends the following steps to counter anti-Roma violence and to improve the socio-economic status of the Roma: condemning attacks when they occur, instituting programs of zero tolerance for violence, strengthening criminal laws to cover more forms of bias-motivated violence, instructing and training police and prosecutors to investigate and prosecute more cases, working in partnership with the victims and their communities, and improving the monitoring and public reporting to ensure that these policies are being implemented and maintained.[39]

Steps for Positive Peace

Positive Peace is defined by the Institute for Economics and Peace as “the attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies.”[40] The key is sustainability of peace, more than only the absence of conflict that comes with negative peace. Ideally for positive peace, the Roma would not face any persecution or suffer from the stereotypes that they are associated with. Employers would readily hire them, their children would not be sent to segregated schools, and the governments of Europe would all recognize and punish hate crimes that were perpetrated against them. If these goals seem lofty and unattainable, it is because there is still not even negative peace for most of the Roma, particularly in Europe. Before positive and sustainable peace can be discussed, the steps toward negative peace addressed above must be taken. Only once the Roma have ceased being attacked and targeted can steps like employment programs or education become more concrete. For there to be positive peace for the Roma, there must first be recognition of past harms and even retributive justice where needed.

[1] Although it should be noted that it has historically been very difficult to determine more than an estimate of Roma population numbers due to peripatetic culture and unwillingness to register their Romani ethnicity for fear of discrimination. Roma. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, June 20, 2019. https://fra.europa.eu/en

/theme/roma Accessed December 10, 2019.

[2] Webley, Kayla. “Hounded in Europe, Roma in the U.S. Keep a Low Profile.” Time. Time Inc., October 13, 2010. http://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2025316,00.html. Accessed December 10, 2019.

[3] “Roma.” European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, June 20, 2019. https://fra.europa.eu/en/theme/roma.

[4] National Institute of Statistics (Romania). 5 July 2013. Accsesed December 15, 2019.

[5] “Who Were the ‘Gypsies’?” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://www.ushmm.org/learn/students

/learning-materials-and-resources/sinti-and-roma-victims-of-the-nazi-era/who-were-the-gypsies. Accessed December 13, 2019.

[6] Sindya N. Bhanoo (11 December 2012). “Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India”. New York Times. Accessed December 13, 2019.

[7] Roma – sub Ethnic Groups. http://rombase.uni-graz.at//cgi-bin/artframe.pl?src=data/ethn/topics/names.en.xml Accessed December 10, 2019.

[8] Antiziganism. https://www.definitions.net/definition/Antiziganism Accessed December 10, 2019.

[9] The Roma Way of Life: Gypsy Work and Family Life. https://www.definitions.net/definition/Antiziganism Accessed December 10, 2019.

[10] György, Fehér, Holly Cartner, and Lois Whitman. Struggling for Ethnic Identity the Gypsies of Hungary. New York: Human Rights Watch, 1993.

[11] Harper, Krista; Steger, Tamara; Filčák, Richard (2009). “Environmental Justice and Roma Communities in Central and Eastern Europe”. Environmental Policy and Governance Env. Pol. Gov. 19 (4): 251–268.

[12] Crowe, David, A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. P. 2.

[13] Crowe, p. 4.

[14] Genocide of European Roma (Gypsies), 1939–1945. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article

/genocide-of-european-roma-gypsies-1939-1945 Accessed December 13, 2019.

[15] Rom-Rymer, Symi. “Roma in the Holocaust”. Moment Magazine (July–August 2011), https://momentmag.com

/roma-in-the-holocaust/ Accessed December 14, 2019.

[16] Katz, Brigit, “London Library Spotlights Nazi Persecution of the Roma and Sinti,” www.smithsonianmag.com

/smart-news/exhibition-spotlights-nazi-persecution-roma-and-sinti-holocausts-forgotten-victims-180973505/ Accessed December 14, 2019.

[17] Rom-Rymer, Symi.

[18] Although it is still problematic. Take, for example, the 2009 and 2010 repatriation of almost 20,000 Roma from France to several other countries, including Romania, which was both controversial has since been condemned as racist and discriminatory. France has since reversed this policy and has implemented attempts to integrate the Roma into France. “French ministers fume after Reding rebuke over Roma”. BBC. September 15, 2010. https:/

/www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-11310560 Accessed December 14, 2019.

[19] Bias Against Roma and Sinti, http://hatecrime.osce.org/what-hate-crime/bias-against-roma-and-sinti Accessed December 15, 2019.

[20] HUNGARY: Violent Attacks Against Roma In Hungary: Time To Investigate Racial Motivation https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/EUR27/001/2010/en/ Accessed December 15, 2019.

[21] Roma in Europe: Demanding Justice and Protection in the Face of Violence, https://www.amnesty.org/en

/latest/news/2014/04/roma-europe-demanding-justice-and-protection-face-violence/ Accessed December 15, 2019.

[22] Praising Roma’s Contributions In Europe, UN Expert Urges End To Rising Intolerance And Hate Speech, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/04/1036291 Accessed December 15, 2019.

[23] Carlo, Andrea, “Opinion:We need to talk about the rising wave of anti-Roma attacks in Europe,” The Independent. 28, July 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/roma-antiziganist-romani-discrimination-italy-matteo-salvini-ukraine-a9024196.html Accessed December 13, 2019.

[24] “The Impact of Legislation and Policies on School Segregation of Romani Children”. European Roma Rights Centre. 2007. p. 8.

[25] Hungary’s Anti-Roma Militia Grows https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2008/0213/p07s02-woeu.html Accessed December 14, 2019.

[26] “Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey” European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2019.

[27] UN General Assembly, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 9 December 1948, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 78, p. 277.

[28] Stanton, George, “The Eight Stages of Genocide,” Genocide Watch, 1996.

[29] Lipstadt, Deborah E. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, Plume, 1994.

[30] United Nations Regional Working Group on Roma, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Minorities/Pages

/UnitedNationsRegionalWGonRoma.aspx Accessed December 14, 2019.

[31] Barany, Zoltan D., The East European Gypsies: Regime Change, Marginality, and Ethnopolitics, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 265–6.

[32] Cottrell, Chris, “Memorial to Roma Holocaust Victims Opens in Berlin,” The New York Times, 24, October 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/25/world/europe/memorial-to-romany-victims-of-holocaust-opens-in-berlin.html. Accessed December 15, 2019.

[33] What is the Roma Genocide? https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/what-roma-genocide Accessed December 13, 2019.

[34] Boudreaux, Richard “Pope Apologizes for Catholic Sins Past and Present”. Los Angeles Times, 13, March 2000.

[35] “Pope apologises to Roma for Catholic discrimination”. 2, June 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-48490942 Accessed December 10, 2019.

[36] Thousands of Romani Survivors Destitute After Reparations Fund Dries Up, https://forward.com/news/1259

/thousands-of-romani-survivors-destitute-after-repa/ Accessed December 10, 2019.

[37] The Persecution of the Roma Is Often Left Out of the Holocaust Story. Victims’ Families Are Fighting to Change That, https://time.com/5719540/roma-holocaust-remembrance/ Accessed December 14, 2019.

[38] Institute for Economics & Peace. Positive Peace Report 2018: Analysing the factors that sustain peace”, Sydney, October 2018.

[39] “Violence Against Roma – Human Rights First,” http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/fd-080924-roma-web.pdf Accessed December 10, 2019.

[40] Institute for Economics & Peace.