Map of Cambodia. Image courtesy of The World Factbook and is in the public domain.

Cambodian Genocide

What

The Cambodian Genocide refers to the attempt of Khmer Rouge party, led by Pol Pot, to turn Cambodia into a classless agrarian society. This resulted in the deaths of 47% of the country’s population from 1975 to 1979.[1]

Where

Cambodia, located in Southeast Asia, sits on the Gulf of Thailand and is bordered by Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam.[2] The capital city is Phnom Penh.

When

Decolonization

Cambodia gained independence from France in 1953 after 100 years of colonial rule.[2] Power was given to Cambodia’s Prince Sihanouk.[3]

In 1970, Prince Sihanouk was removed in a military coup led by his own Lieutenant-General Lon Nol.[4] Lon Nol became president of the new Khmer Republic while Prince Sihanouk and his followers joined forces with a communist guerrilla organization, the Khmer Rouge.[5]

Rise of the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge guerrilla movement, founded in 1960 and led by Pol Pot, envisioned a new Cambodia with the aim to return Cambodia to “Year Zero,” in which all citizens would participate in rural work projects and all Western innovations and practices would be eliminated.[6] Pol Pot brought in Chinese communist training tactics and Viet Cong support for his troops and produced a formidable military force.[7]

In 1970, the Khmer Rouge launched a civil war against the U.S.-backed Khmer Republic, which was led by Lieutenant-General Lon Nol.[8] Lon Nol’s pro-Western government demanded the withdrawal of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces from Cambodia.[9] The Khmer Rouge guerillas overthrew Lon Nol’s government in 1975, and within days the Khmer Rouge began the mission to reconstruct Cambodia on a non-literate, anti-modern, agrarian model.[10]

To achieve the “ideal” communist model, the Khmer Rouge required all Cambodians to labor on collective farms, and anyone opposing this system would be eliminated.[11] Those targeted for elimination included intellectuals, educated people, professionals, monks, religious enthusiasts, Buddhists, Muslims, Christians, ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, and Cambodians with Chinese, Vietnamese, or Thai ancestry. The Khmer Rouge also executed its own members who were suspected of treachery.[12]

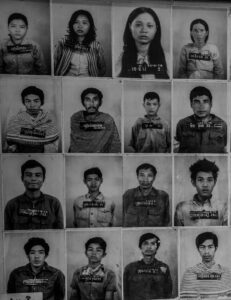

Victims of the Khmer Rouge. Image courtesy of Ted McGrath is cropped and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Under threat of death, Cambodians nationwide were forced from their homes and villages. People from cities were forcibly evacuated to the countryside. Those incapable of making the journey to collectivized farms and labor camps were killed on the spot. People who refused to leave their homes were killed, along with anyone who opposed the new regime. All political and civil rights of citizens were abolished.[13] Children were taken from their parents and placed in forced labor camps.[14] Factories, schools, businesses, universities, hospitals, and all private institutions were shut down and former owners, employees, and their extended families were murdered. Religion was banned, Buddhist monks and Christian missionaries were killed, and temples and churches were burned.[14]

Most of the killing was due to the extremist goal of a militant communist transformation. People were shot for speaking a foreign language or wearing glasses, which was taken to be a sign of an educated and Westernized person, or for smiling or crying, which were signs of emotion characterized as weakness.[14]

Cambodians were slave laborers who worked on starvation-level rations for long hours. They lived in public communes, with constant food shortages and rampant diseases.[15] Forced labor, starvation, injury, and illness meant that many Cambodians became incapable of performing physical work, and they were killed outright by the Khmer Rouge.[15]

These conditions continued until Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1978 and ousted the government in 1979. The pre-genocide population was approximately 7 million; by the end of this period, civilian deaths were estimated at over 3 million people.[40][15]

Cambodians continued to suffer after the fall of the Khmer Rouge. Countless numbers of people fled to Thailand. Many died of starvation or stepped on land mines that soldiers had placed along the western border to prevent their victims from fleeing. Those who made it to Thailand brought malaria, typhoid, cholera, and a host of other illnesses into the refugee camps.[15]

How

Many Cambodians had become disenchanted with Western democracy due to the huge loss of Cambodian lives from the US bombing of Cambodia in the Vietnam War. Pol Pot’s communism brought images of new hope for Cambodia. By 1975, Pol Pot’s force had grown to over 700,000.[16] However, it became clear within days of the Khmer Rouge takeover in 1975 that these hopes were impossible.[17]

While the Khmer Rouge was gaining power, the U.S. government had little interest in the events that were. The American Embassy was concerned with Cambodia solely in relation to the Vietnam War.[18]

Response

When the Vietnamese took control in 1979, Cambodia was in ruins. The economy had failed, and all professionals, engineers, technicians, and planners who could potentially reorganize Cambodia had been killed in the genocide or had fled.[19] The US and UK offered financial and military support to only the Khmer Rouge forces in exile, who had sworn opposition to Vietnam and communism. The Vietnamese began to be viewed as unwelcome occupiers, not only because of their ten-year stay in Cambodia, but also because of the legacy of animosity between the two countries.[20] This hostile Vietnamese occupation and the threat of Khmer Rouge guerilla forces left Cambodia in devastation until Vietnam’s withdrawal in 1989.[21]

Cambodian leadership implemented many isolationist policies under the Pol Pot regime in order to seal the country off from global scrutiny. The regime’s vision included rejecting any foreign influence, resulting in international media being banned and diplomatic relations severed. By doing such, the Khmer Rouge was able to limit any global awareness of the events occurring, which contributed to the longevity of the regime.

In 1991, a peace agreement was finally reached. The nation’s first democratic elections were held in 1993.[21]

In the early 1990s, mass graves were uncovered throughout Cambodia that held hundreds of skeletal remains from Khmer Rouge execution grounds, known as killing fields. Survivors suffered severe levels of post-traumatic stress disorder that often went undiagnosed and untreated in a country with almost no mental health and other resources.[24]

A 2009 report on data taken from 1975-1979 found that 3,314,768 people, an estimated 47% of the population, lost their lives in the “Pol Pot time.”[23] This report was prepared by two Cambodian Judges who were a part of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC).

Retributive Justice Efforts

Many suspected perpetrators were killed in the military struggle with Vietnam or eliminated as internal threats to the Khmer Rouge itself. In 1997, Pol Pot was arrested by Khmer Rouge members; a “mock” trial was staged, Pol Pot was found guilty and was under house arrest, imposed by his own party members, when he apparently died of natural causes in 1998. The last Khmer Rouge members were officially disbanded in 1999.[26]

The Trial Chamber at the initial hearing in Case 002. Image courtesy of Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The UN called for a Khmer Rouge Tribunal in 1994. The ECCC was established in a hybrid of national and international courts and procedures. Trials began in 2007 and concluded in 2022.[25]

The ECCC has been criticized for handing down only three convictions despite operating for 16 years at a cost of $337million.[26] This is in part due to the court prosecuting only senior leaders most responsible for the crimes. Additionally, former Prime Minister of Cambodia and Khmer Rouge member Hun Sen opposed further indictments. Several government officials are former Khmer Rouge members and there have been considerable efforts to protect them, including denying access to witnesses because of the accused’s position.

Kaing Guek Eav, known as “Comrade Duch,” Nuon Chea, and Khieu Samphan are the only accused perpetrators to be convicted.[27] Duch was found guilty of crimes against humanity and war crimes and was sentenced to life imprisonment.[28] Nuon Chea was found guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide and was sentenced to life imprisonment.[28] Khieu Samphan was found guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide and sentenced to life imprisonment.[28]

Future

A child beggar in front of Banteay Srei Temple, 2014. Image courtesy of Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) /Makara Ouch is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Human rights abuses soared in recent years. In 2017, the leader of Cambodia’s opposition party was arrested, and the party was dissolved, leaving no opposition to contest the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) in the 2018 elections.[20] Therefore, in 2018 the CPP, led by former Prime Minister Hun Sen, secured all 125 of Cambodia’s National Assembly seats to create a one-party rule in the state. The Prime Minister has continued to prevent any dissent by targeting political opponents human rights workers, social activists, and intellectuals [29] with arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial killings, and denial of citizens’ rights to protest, along with limiting freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly.[29] When Prime Minister Hun Sen resigned in 2023, he appointed his son Hun Manet as his successor. Hun Sen remains influential as he heads the CPP and serves as the president of parliament.

Other human rights concerns in Cambodia include widespread poverty which is compounded by high levels of illiteracy and unemployment and limitations on education and employment. Powerful elites in the region take land from rural and indigenous communities which displace many and worsen social inequality.[42]

Extensive placement of landmines during the war remains a threat to many Cambodians today. Much land is unusable for agriculture or for civilian use due to undetonated and visually concealed landmines. Landmine explosions have claimed over 19,000 lives from 1979-2024.[41]

Political opposition leaders, such as Sam Rainsy continue to live in exile, highlighting issues of political repression and limitation on freedom of expression.[43] Sun Chanthy, the leader of the National Power Party, was sentenced to two years in prison, effectively banning him from political participation.[32] Similarly an investigative journalist, Mech Dara, was arrested shortly after covering human trafficking and online scams in the region.[33] These instances highlight a growing concern that the government is using legal and illegal means to suppress any dissent and the free flow of information regarding issues within the country.

China invests heavily in Cambodia for access to valuable natural resources. Japan also contributes large investments, including aid, to compete with China for influence and resources.[29] In 2019 the US both suspended aid to the Cambodian government and passed the “Cambodia Democracy Act” to impose sanctions against specific Cambodian officials involved in current human right violations.[30] In 2020, the EU partially suspended trade preferences in Cambodia due to continued deterioration of rights.[31]

Girls in Cambodia are at risk of becoming victims of human trafficking or gender-based violence. Image courtesy of James Handlon is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Cambodia has a history of human trafficking, beginning in 1990 with the post-Khmer Rouge era. In 2006 Cambodia was considered a source, transit, and destination country for trafficking, particularly the trafficking of young Cambodian girls into China for forced marriage and sexual slavery.[34][36] This is worsened by sexual and gender-based violence. The US has imposed sanctions on prominent businesspeople who participate in trafficking activities.[35]

While the United Nations has taken no formal action, many UN experts continue to call on Cambodia to end the harassment and prosecution of human rights defenders and civil society activists.[39]

Key challenges for Cambodia include limited judicial capacity and widespread corruption, human trafficking, land grabs, gender-based violence, landmines, poverty, and restrictions on expression and political participation.

This page was updated by Evelyn Middleton, December 2024.

References

[1] Al Jazeera. (2012, February 3). Key facts on the Khmer Rouge. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2012/2/3/key-facts-on-the-khmer-rouge

[2] Tolerance Building Dialogue. (n.d.) Cambodia. Tolerance Building Dialogue. https://tolerance.tavaana.org/en/cambodia/

[3] Tufts University. (2015, August 7). Cambodia: U.S. bombing, civil war, and the Khmer Rouge. https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/2015/08/07/cambodia-u-s-bombing-civil-war-khmer-rouge/

[4] UPI. (1985, November 18). Lon Nol seized control of Cambodia in 1970. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1985/11/18/Lon-Nol-seized-control-of-Cambodia-in-a-1970/9748501138000/

[5] Tolerance Building Dialogue, op. Cit.

[6] Britannica. (2024, December 19). Khmer Rouge. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Khmer-Rouge

[7] Kiernan, Ben. (2008). The Pol Pot regime: Race, power, and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79, 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

[8] History.com. (n.d.). Lon Nol ousts Prince Sihanouk. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/lon-nol-ousts-prince-sihanouk

[9] Global Security. (n.d.). History of Lon Nol in Cambodia. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/cambodia/history-lon-nol.htm

[10] Tolerance Building Dialogue, op. Cit.

[11] Tolerance Building Dialogue, op. Cit.

[12] Hopen, Bernadette. (2017, January 7). Never again: The Cambodian genocide. Medium https://medium.com/@BWHopen/never-again-the-cambodian-genocide-2d9d17a2b7d4

[13] Tolerance Building Dialogue, op. Cit.

[14] Edweb Project. (n.d.). The Work Camps: Life and Death in the Farmin Cooperatives http://www.edwebproject.org/sideshow/khmeryears/camps.html

[15] Peace Pledge Union. (n.d.). Genocide in Cambodia. Peace Pledge Union. http://www.ppu.org.uk/genocide/g_cambodia1.html

[16] Britannica. (2024, November 13). Lon Nol: Biography. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lon-Nol

[17] Tolerance Building Dialogue, op. Cit.

[18] Omar, Oliver. (2016, May 24). U.S. Policy Towards Cambodia between 1969-1973. E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2016/05/24/an-analysis-of-u-s-policy-towards-cambodia-between-1969-1973/#google_vignette

[19] History.com Editors. (2018, August 21). Pol Pot. History.com. https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/pol-pot

[20] BBC News. (2018, July 27). Hue Sen: Cambodia’s strongman prime minister. BBC News https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-23257699

[21] PPU, op. cit.

[22] Department of Justice. (2015). Cambodia 2015 Human Rights Report. DoJ. https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/252965.pdf

[23] Etcheson, Craig. (2000, April). 3 million KR dead and still counting research. Phnom Penh Post. https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/33-million-kr-dead-and-still-counting-researcher

[24] University of Minnesota. (n.d.) Cambodia. University of Minnesota. https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/cambodia

[25] UN News. (2022, September 22). Cambodia: UN-backed tribunal ends with conviction upheld for last living Khmer Rouge leader. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/09/1127521

[26] Seavmey, M. (2022, September 21). $337 Million: The Cost of Khmer Rouge Justice.

[27] BBC. (n.d). History: Pol Pot. BBC Archives. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/pot_pol.shtml

[28] Lambourne, W. (2014, May 1). Justice After Genocide: Impunity and the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. International Association of Genocide Scholars. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1024&context=gsp

[29] Human Rights Watch. (2019). Cambodia; Events of 2019. HRW. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/cambodia

[30] Congress.gov. (2019, January 11). H.R. 526 – Cambodia Democracy Act of 2019. Congress.com. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/526

[31] Human Rights Watch. (2020, February 13). Cambodia: EU Partially Suspends Trade Preferences. HRW. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/02/13/cambodia-eu-partially-suspends-trade-preferences

[32] Cheang, S. & Peck, G. (2024, December 26). Cambodian court gives an opposition leader 2-year prison term, keeping pressure on critics. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/cambodia-hun-manet-repression-lawfare-sun-chanthy-f75d60b4cb614733fd2e107d63f1152f

[33] McPherson, P. (2021, October 21). Cambodia charges investigative journalist Mech Dara, who exposed trafficking and scam compounds, with incitement. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/cambodia-arrests-investigative-journalist-who-exposed-trafficking-scam-compounds-2024-10-01/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[34] U.S. Department of State. (2024). 2024 Trafficking in Persons Report: Cambodia. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/cambodia/

[35]. U.S. Department of Treasury. (2024, September 12). Treasury Sanctions Cambodian Tycoon and Businesses Linked to Human Trafficking and Forced Labor in Furtherance of Cyber and Virtual Currency Scams. U.S. Department of Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2576

[36] David, S. (2024, October 21). Cambodia: Govt. Committed to step up the fight to combat human trafficking. Khmer Times. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/cambodia-govt-committed-to-step-up-the-fight-to-combat-human-trafficking/

[37] AP News. (2024, November 24). Prominent Cambodia environmentalist is arrested while investigating illegal logging. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/cambodia-environmentalist-arrested-ouch-leng-5acc57ec9fce217f557fa6bc3d1d046f

[38] United Nations. (2024). How the UN is supporting The Sustainable Development Goals in Cambodia. United Nations Cambodia. https://cambodia.un.org/en/sdgs?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[39] United Nations Human Rights. (2024, April). Cambodia must end harassment of human rights defenders: UN experts. UNHR. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/04/cambodia-must-end-harassment-human-rights-defenders-un-experts?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[40] Rummel, R. J. (n.d.). Statistics Of Cambodian Democide Estimates, Calculations, And Sources. University of Hawai’i. https://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.CHAP4.HTM

[41] XINHUA. (2025-1-08). Cambodia sees spike in landmine ERW casualties in 2024. XINHUA. https://english.news.cn/20250108/a14b381e5a9a400c91feb0a04946c056/c.html#:~:text=According%20to%20Kosal%2C%20from%201979,affected%20by%20landmines%20and%20ERWs.

[42] Kingdom of Cambodia. (2019). Series Thematic Report on Literacy and Educational Attainment in Cambodia. Kingdom of Cambodia. https://www.nis.gov.kh/nis/Census2019/Thematic%20Report%20Literacy%20and%20Educational%20Attainment-Eng.pdf

[43] Human Rights Watch. (2015, January 12). 30 years of Hun Sen. Violence, Repression and Corruption in Cambodia. HRW. https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/01/12/30-years-hun-sen/violence-repression-and-corruption-cambodia