Laos

What

Laos experienced over fifteen years of civil war from 1959 to 1975 followed by a continuing low-level insurgency. The Pathet Lao, a communist military and political organization, achieved control during the conflict and implemented restrictive censorship policies to consolidate its rule. The Hmong, a minority ethnic group, fought the Pathet Lao during the civil war and conflict continues between the groups today. The Pathet Lao began a genocidal reprisal campaign against the Hmong, destroying villages, perpetrating mass rapes, and killing tens of thousands. At least 100,000 Hmong civilians have been killed by the Pathet Lao during the war and after. [1]

Since the civil war ended, many Hmong have isolated themselves in the jungle for fear of further violence and continued attacks from the Pathet Lao. The politically repressive Laotian government and local officials also persecute Christians, other religious minorities, and human rights activists.

Where

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (LPDR), or Laos, is a communist state in Southeast Asia, bordered by Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, China, Myanmar, and the Mekong River. It is rich with gold, tin, gypsum, gemstones, and rubber. [2] The population numbers about 7.9 million; the Lao, at 53%, are the majority ethnic group. [3] Buddhism is the nation’s primary religion, although other faith minorities exist including atheists, Animists, Christians, Muslims, and Baha’i. [4]

The Hmong are the third-largest ethnic group in Laos, composing 9% of the population. [5]

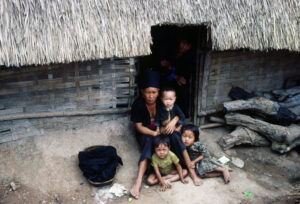

A Laotian Hmong refugee family in Thailand. Image courtesy of UN Photo/John Isaac is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

When

In 1954, Laos gained independence from France and became a constitutional monarchy. Civil war broke out between royalists and the Pathet Lao, a communist political group. [6] The United States wanted to prevent the Pathet Lao from taking over Laos, and the CIA trained and financially backed a resistance force known as the “Secret Army,” largely comprised of ethnic Hmong. [7] At its peak, the Secret Army included 30,000 soldiers. [8] U.S. forces remained active in the Laotian Civil War for more than 15 years.

In 1975, the Pathet Lao seized power and the U.S. military withdrew from Laos, leaving Secret Army soldiers defenseless. Much of Laos’s Hmong population fled to Thailand. [9] The Pathet Lao imprisoned remaining Secret Army members in ’re-education camps’ where they faced political indoctrination, forced labor, and starvation. [10][11]

Communist soldiers invaded Hmong villages and arrested, raped, and slaughtered civilians, only sparing Hmong who supported the Pathet Lao. [12] Tens of thousands of Hmong, referred to as the “Jungle Hmong,” fled into the jungle and engaged in sporadic resistance against the government. [13] They have lived in scattered groups and faced brutal attacks from the Laotian military for over four decades.

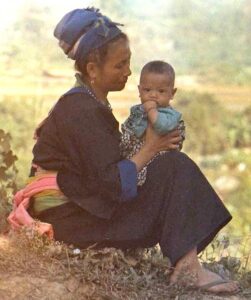

Hmong woman and child, 1973. Image courtesy of grjenkins is unmodified and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

How

Since the end of the civil war, the Laotian government has denied the Jungle Hmong’s existence while also giving military orders to shoot them on sight. [14] To avoid being identified and massacred, the Jungle Hmong often stay in temporary shelters for short periods. [15] They are therefore unable to grow crops or to access sanitation services, basic education, or medical care. [16] The media and the government characterize them as armed rebels, but the surviving Jungle Hmong are mostly starving women and children, without the capacity for organized resistance. [17]

Over the years, many Jungle Hmong have surrendered to Lao authorities [18] and have been arrested and held without charge in dire conditions. [19] Others have attempted to flee to Thailand and elsewhere. Hmong refugees in Thailand are treated as illegal immigrants and are kept in isolated refugee camps. [20] In the early 2000s, Thailand repatriated thousands of Hmong back to Laos, where they were often “disappeared.” [21] An unknown number of these Hmong continue to inhabit Laos’s rural, mountainous provinces, fearing state oppression. [22]

Laos maintains extensive restrictions on political expression. It is a one-party state led by the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP), which tolerates no organized opposition. [23] The LPRP only allows party-approved candidates to run for office, oversees media, and runs security agencies that surveil the country’s population for signs of dissent. [24] Citizens suspected of criticizing the regime face detention at local police stations, re-education training in camps, and imprisonment. [25] Defendants lack due process and the right of appeal. [26]

China is funding construction of a hydroelectric dam in Laos. Image courtesy of Xayaburi Dam Construction is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Today

China and Laos share a border and Communist-style governments. Over the last decade, Chinese investment in Laos increased dramatically as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a global infrastructure development project. China invested in railways, hydroelectric power, schools, roads, military hospitals, mining, and tourism projects in Laos. [27]

The Laotian government is developing natural resources around Phou Bia Mountain in the Xaisomboun Province of central Laos. [28] A group of Hmong called the ChaoFa Hmong, including communities living in hiding there since the Laotian Civil War, inhabit this isolated region and are subjected to military violence. [29] Various human rights organizations accused the Laotian government of uncompensated land appropriation and forced displacement in this region to make space for Chinese-funded development projects. [30] The Phou Bia region’s natural environment faces significant degradation through Chinese-funded construction of a hydroelectric dam, the mining of precious metals, and logging. [31]

In 2021, the government sealed off the area around Phou Bia Mountain and launched a military clearance operation to prepare it for a tourist project. [32] Some Hmong claimed that Laos used chemical weapons to clear the territory. [33] A report by the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) at the United Nations describes hunger, massacres, and the surrender of Hmong who are then held in military-controlled camps. [34] Upon arrival in the camps, men were detained and interrogated for several months [35] and women reported sexual assault and slavery. [36] Families living in the camps lack safe drinking water, food, and stable housing, and they must barter labor for bare necessities. [37]

Outside Laos, information is limited about this situation because the government blocks access for journalists and human rights groups. [38] In 2020, nine UN Special Rapporteurs and the UN Working Group on Enforced Disappearances wrote a letter of concern over the situation to the Laotian government. [39] However, since 2021, few reports on the ChaoFa Hmong’s condition have emerged. There is increasing fear among the Hmong and the international community that the government is heading towards more exterminatory actions. [40]

Outside the Xaisomboun Province, Hmong face lack of economic opportunity, discrimination, and persecution. [41] The government circumscribes Hmong freedom of movement. [42] State schools employ Lao as the “only language of instruction,” limiting Hmong cultural continuance and encouraging assimilation. [43] Several Hmong, like human rights activist Chue Youa Vang, have been killed or disappeared in recent years. [44]

Christian Hmong, and Christians generally, face faith-based repression. Non-Christian villagers and government officials often expel Christians—especially new converts—from their villages and pressure Christian families to sign documents renouncing their faith, lest they also experience displacement. [45] Village chiefs bar Christians from celebrating holidays like Christmas and prevent Christian burials in communal cemeteries. [46] Christians across Laos report discrimination in accessing public services, including education and government assistance. [47] Some regions prohibit Christian youth from attending public school, and non-Buddhists are advised to conceal their faith if they wish to work for the government. [48] Christian groups must overcome burdensome hurdles to register themselves with the Laotian government, travel throughout the country, and acquire property. [49] Prominent faith leaders have also been killed: in 2020, an unknown assailant abducted and murdered Hmong Christian leader Cha Xiong. [50] Other minority religious groups endure similar maltreatment. [51]

Future

The UN will conduct its fourth Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Laos’s human rights situation in April 2025. Several advocacy organizations submitted briefs to the UN documenting the government’s persecution of the Hmong, with the goal of encouraging further reporting on the Hmong’s repression. [52] However, as long as Laotian authorities silence political dissent, cede communal and individual land for economic development without recompense, and employ state forces against vulnerable ethnic and religious groups, generating such change remains a challenge.

This page was updated by Bekir Hodzic, December 2024.

References

[1] University of Central Arkansas. 2024. 37. Laos (1954-present). University of Central Arkansas. https://web.archive.org/web/20240407184424/https://uca.edu/politicalscience/home/research-projects/dadm-project/asiapacific-region/laos-1954-present/

[2] Central Intelligence Agency. (2024, December 12). Laos. The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/laos/

[3] Central Intelligence Agency. (2024, December 12). Laos. The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/laos/

[4] 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Laos. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/laos/

[5] Central Intelligence Agency. (2024, December 12). Laos. The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/laos/

[6] Caicedo, F. V. & Riano, J. F. (2020, November 29). Apocalypse Laos: The devastating legacy of the ‘Secret War.’ Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/apocalypse-laos-devastating-legacy-secret-war; Laos. (n.d.). John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/laos

[7] Amnesty International. (2007, March 23). Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Hiding in the jungle – Hmong under threat. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ASA26/003/2007/en/

[8] The Split Horn: The Journey. (n.d.). PBS. https://www.pbs.org/splithorn/story1.html

[9] Weiner, T. (2008, May 11). Gen. Vang Pao’s Last War. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/11/magazine/11pao-t.html; Fuller, T. (2007, December 17). Old U.S. Allies, Still Hiding in Laos. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/17/world/asia/17laos.html

[10] Currie, L. C. (2008). The Vanishing Hmong: Forced Repatriation to an Uncertain Future. North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation, 34(1), 325-370. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/151516438.pdf

[11] Currie, L. C. (2008). The Vanishing Hmong: Forced Repatriation to an Uncertain Future. North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation, 34(1), 325-370. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/151516438.pdf

[12] Jacobs, B. W. (1996). No-Win Situation: The Plight of the Hmong, America’s Former Ally. Boston College Third World Law Journal, 16(1), 139-166. https://lira.bc.edu/work/sc/8f449e44-277c-4511-b7fd-587c093102c2

[13] Perrin, A. (2003, April 28). Welcome to the Jungle. Time Magazine. https://time.com/archive/6894196/welcome-to-the-jungle-2/

[14] van der Made, J. (2017, May 12). Hmong face military in Laos jungle in fallout from Vietnam war. RFI. https://www.rfi.fr/en/asia-pacific/20171204-anno-2017-vietnam-war-still-rages-secretly-laos-hmong

[15] Amnesty International. (2007, March 23). Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Hiding in the jungle – Hmong under threat. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ASA26/003/2007/en/

[16] Amnesty International. (2007, March 23). Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Hiding in the jungle – Hmong under threat. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ASA26/003/2007/en/

[17] Currie, L. C. (2008). The Vanishing Hmong: Forced Repatriation to an Uncertain Future. North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation, 34(1), 325-370. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/151516438.pdf

[18] The Associated Press. (2006, December 14). 405 Hmong Holdouts From Vietnam War Era Surrender in Laos. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/14/world/asia/14laos.html

[19] Amnesty International. (2007, March 23). Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Hiding in the jungle – Hmong under threat. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ASA26/003/2007/en/

[20] Amnesty International. (2008, November 17). Thailand: Life at a Dead End: Lao Hmong refugees detained in Thailand. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa39/007/2008/en/; Thailand: Protect Hmong Refugees. (2007, August 30). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/08/30/thailand-protect-hmong-refugees.

[21] UN rights experts call for end to Thai expulsion of Lao Hmong. (2009, December 31). United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2009/12/325602; Amnesty International. (2008, November 17). Thailand: Life at a Dead End: Lao Hmong refugees detained in Thailand. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa39/007/2008/en/

[22] Cano, M. M., Solway, A., and Bunche, R. (2021, April 23). Hmong in Isolation: Atrocities against the indigenous Hmong in the Xaisomboun Region of Laos. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. https://unpo.org/hmong-in-isolation-atrocities-against-the-hmong-in-laos/

[23] Laos. (n.d.). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/laos/freedom-world/2024

[24] Laos. (n.d.). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/laos/freedom-world/2024

[25] Laos. (n.d.). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/laos/freedom-world/2024; Laos. (n.d.). Reporters Without Borders. https://rsf.org/en/country/laos

[26] Laos. (n.d.). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/laos/freedom-world/2024

[27] Albert, E. (2019, April 24). China Digs Deep in Landlocked Laos. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2019/04/china-digs-deep-in-landlocked-laos/; Horton, C. (2018, September 25). Capital of Laos Seeks Stronger Ties to China. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/25/business/vientiane-laos-china-investment.html

[28] Cano, M. M., Solway, A., and Bunche, R. (2021, April 23). Hmong in Isolation: Atrocities against the indigenous Hmong in the Xaisomboun Region of Laos. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. https://unpo.org/hmong-in-isolation-atrocities-against-the-hmong-in-laos/

[29] Cano, M. M., Solway, A., and Bunche, R. (2021, April 23). Hmong in Isolation: Atrocities against the indigenous Hmong in the Xaisomboun Region of Laos. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. https://unpo.org/hmong-in-isolation-atrocities-against-the-hmong-in-laos/

[30] Unrepresented Nations and People Organization and Congress of World Hmong People. Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Universal Periodic Review 48th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic: The Hmong Peoples in Laos. (2024, October 24). Unrepresented Nations and People Organization. https://unpo.org/unpo-and-the-cwhp-advocate-for-hmong-rights-in-laos-through-upr-submission-and-report-for-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-cultural-rights/

[31] Unrepresented Nations and People Organization and Congress of World Hmong People. Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Universal Periodic Review 48th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic: The Hmong Peoples in Laos. (2024, October 24). Unrepresented Nations and People Organization. https://unpo.org/unpo-and-the-cwhp-advocate-for-hmong-rights-in-laos-through-upr-submission-and-report-for-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-cultural-rights/

[32] Finney, R. (2021, April 1). Lao Government Troops Launch New Assault Against Hmong at Phou Bia Mountain. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/laos/assault-04012021160502.html

[33] Unrepresented Nations and People Organization and Congress of World Hmong People. Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Universal Periodic Review 48th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic: The Hmong Peoples in Laos. (2024, October 24). Unrepresented Nations and People Organization. https://unpo.org/unpo-and-the-cwhp-advocate-for-hmong-rights-in-laos-through-upr-submission-and-report-for-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-cultural-rights/

[34] Cano, M. M., Solway, A., and Bunche, R. (2021, April 23). Hmong in Isolation: Atrocities against the indigenous Hmong in the Xaisomboun Region of Laos. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. https://unpo.org/hmong-in-isolation-atrocities-against-the-hmong-in-laos/

[35] Cano, M. M., Solway, A., and Bunche, R. (2021, April 23). Hmong in Isolation: Atrocities against the indigenous Hmong in the Xaisomboun Region of Laos. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. https://unpo.org/hmong-in-isolation-atrocities-against-the-hmong-in-laos/

[36] Unrepresented Nations and People Organization and Congress of World Hmong People. Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Universal Periodic Review 48th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic: The Hmong Peoples in Laos. (2024, October 24). Unrepresented Nations and People Organization. https://unpo.org/unpo-and-the-cwhp-advocate-for-hmong-rights-in-laos-through-upr-submission-and-report-for-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-cultural-rights/; Cano, M. M., Solway, A., and Bunche, R. (2021, April 23). Hmong in Isolation: Atrocities against the indigenous Hmong in the Xaisomboun Region of Laos. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. https://unpo.org/hmong-in-isolation-atrocities-against-the-hmong-in-laos/

[37] Unrepresented Nations and People Organization and Congress of World Hmong People. Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Universal Periodic Review 48th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic: The Hmong Peoples in Laos. (2024, October 24). Unrepresented Nations and People Organization. https://unpo.org/unpo-and-the-cwhp-advocate-for-hmong-rights-in-laos-through-upr-submission-and-report-for-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-cultural-rights/

[38] 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Laos. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/laos/

[39] United Nations. (2020, August 28). Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food; the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment; the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context; the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples; the Special Rapporteur on minority issues; the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights and the Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=25491

[40] Unrepresented Nations and People Organization and Congress of World Hmong People. Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Universal Periodic Review 48th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic: The Hmong Peoples in Laos. (2024, October 24). Unrepresented Nations and People Organization. https://unpo.org/unpo-and-the-cwhp-advocate-for-hmong-rights-in-laos-through-upr-submission-and-report-for-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-cultural-rights/

[41] Atrocity Crimes Risk Assessment Series: Lao People’s Democratic Republic’s. (March 2021). Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/6317/Risk_Assessment_laos_vol15_march2021.pdf

[42] Laos. (n.d.). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/laos/freedom-world/2024

[43] Alston, P. (2019, February 4). Report on the Country visit to the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/calls-for-input/report-country-visit-lao-peoples-democratic-republic

[44] 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Laos. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/laos/; Laos: States should ask “Where is Sombath?” at upcoming review of human rights record. (2024, December 15). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/12/15/laos-states-should-ask-where-sombath-upcoming-review-human-rights-record; Laos: United Nations committee urges an end to reprisals against women human rights defenders. (2024, November 4). International Federation for Human Rights. https://www.fidh.org/en/region/asia/laos/laos-un-committee-urges-an-end-to-reprisals-against-women-human

[45] 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Laos. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/laos/

[46] International Federation for Human Rights and Lao Movement for Human Rights. (2024, October 11). Universal Periodic Review (UPR) — 49th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR). International Federation for Human Rights. https://www.fidh.org/en/region/asia/laos/laos-report-on-the-human-rights-situation-for-the-universal-periodic; 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Laos. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/laos/

[47] 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Laos. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/laos/.

[48] 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: Laos. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/laos/

[49] Laos. (n.d.). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/laos/freedom-world/2024

[50] International Federation for Human Rights and Lao Movement for Human Rights. (2024, October 11). Universal Periodic Review (UPR) — 49th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR). International Federation for Human Rights. https://www.fidh.org/en/region/asia/laos/laos-report-on-the-human-rights-situation-for-the-universal-periodic

[51] International Federation for Human Rights and Lao Movement for Human Rights. (2024, October 11). Universal Periodic Review (UPR) — 49th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR). International Federation for Human Rights. https://www.fidh.org/en/region/asia/laos/laos-report-on-the-human-rights-situation-for-the-universal-periodic

[52] Unrepresented Nations and People Organization and Congress of World Hmong People. Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Universal Periodic Review 48th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic: The Hmong Peoples in Laos. (2024, October 24). Unrepresented Nations and People Organization. https://unpo.org/unpo-and-the-cwhp-advocate-for-hmong-rights-in-laos-through-upr-submission-and-report-for-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-cultural-rights/; International Federation for Human Rights and Lao Movement for Human Rights. (2024, October 11). Universal Periodic Review (UPR) — 49th Session: Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR). International Federation for Human Rights. https://www.fidh.org/en/region/asia/laos/laos-report-on-the-human-rights-situation-for-the-universal-periodic