Genocide of the Herero and Nama

Map of Africa with Namibia indicated in green. Map courtesy of The World Factbook is located in the public domain.

Where

Namibia is bordered by South Africa, Botswana, Angola, Zambia, and the Atlantic Ocean.

Namibia, then called South West Africa, was a German colony from 1884 to 1915.[1] Germany’s colonial rule ended with South Africa’s military occupation of Namibia during World War I. South Africa maintained apartheid-style control over the country until independence in 1990. The UN renamed the country Namibia in 1968.[2]

What

German colonial forces committed a genocide against the indigenous Herero and Nama people in South West Africa from 1904 to 1908, in the earliest genocide of the 20th century.

South West Africa became a German colony in 1884 and tensions grew between the Germans and local communities, particularly the Herero and Nama. Germans purchased land that was historically Herero- or Nama-held land, and the Herero and Nama people became subjected to forced labor and oppressive colonial policies.[3]

Herero and Nama people rebelled against German rule in 1904 and 1905.[4] These uprisings killed 123 German settlers and increased tensions between local communities and German settlers. German General Lothar von Trotha issued an extermination order against the Herero people, and the German military responded with brutal force, later extending similar tactics to the Nama.[5]

The Herero were forcibly moved into the Omaheke Desert where many died of thirst and starvation.[6] Survivors were placed in concentration camps where they were subjected to forced labor, abuse, starvation, and medical experimentation.[7] The Nama people experienced similar conditions.

Herero and Nama people were chained and subjected to abuse, starvation, and forced labor. Image is located in the public domain.

It is estimated that 80% (approximately 65,000 people) of the Herero people and 50% (around 10,000 people) of the Nama people perished over the four-year genocide.[8]

How

The Herero and Nama genocide was rooted in European imperialism, racism, and colonialism during the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Germany was given South West Africa during the Berlin Conference in 1884, an attempt by European powers to control trade and force colonization in Africa.

Germany pushed indigenous communities off their lands to make space for German settlers.[9] The colonial administration used forced labor, cattle confiscation, and unequal legal systems to undermine and control indigenous communities.[10]

The German military used methodical planning to commit the genocide. The Vernichtungsbefehl was an October 1904 execution order that stated every Herero in the region was to be executed.[11] This type of order was unprecedented and marked a clear shift from a strategy of military confrontation to systematic annihilation. The order was later rescinded due to international pressure, but the impact was irreversible – genocidal practices were already established, including extermination camps, concentration camps, such as one at Shark Island, which held prisoners in horrific conditions, and brutal medical experiments.[12]

This genocide had far-reaching implications. Survivors were stripped of their identity, rights, property, and cultural history.

Developing a Genocide ‘Playbook’

The tactics developed and implemented during this genocide laid the foundation for future atrocities including the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust. The use of death marches, concentration camps, forced labor, and extermination orders were the first genocidal methods to be used by a modern state, and these tactics were repeated during the Armenian genocide, 1915-1916, and the Holocaust, 1933-1945.[14] Many of the leading perpetrators of the Herero and Nama genocide went on to become instrumental in developing and implementing the policies of the ‘final solution’ for the extermination of Europe’s Jews during World War II.

Response

Very little has been done in response to one of the most complete genocides in history. A significant portion of Namibia’s land is still owned by the white descendants of German colonialists who perpetrated the genocide. Descendants of Herero and Nama genocide survivors and victims remain among the poorest and most disadvantaged people in Namibia.[17]

There has been growing international pressure on Germany to acknowledge and atone for its colonial atrocities. In 2021, Germany officially recognized the events as genocide and offered an apology, along with a financial package of over $1.1 billion for development projects in Namibia.[18] However, Herero and Nama leaders criticized the agreement for lacking direct reparations and for excluding their representatives from all negotiations.

In addition, descendants have tried unsuccessfully to bring charges in U.S. courts against the German government and the German railway lines for their responsibility in the mass atrocities. Issues have been raised at the United Nations as well.

The legacy of the genocide continues to influence Namibian society today, particularly in ongoing debates about land reform, historical memory, and justice for the descendants of those who suffered.[19]

Today

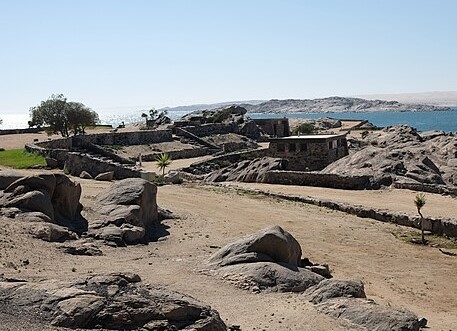

Shark Island is considered a sacred heritage and memorial site for Herero and Nama people. Image courtesy of Johan Jönsson (Julle) is cropped and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

In June 2024, the Namibian and German governments agreed to an undisclosed increase in financial support, reframing the funds as an “atonement of guilt” rather than as reparations. Germany acknowledged the events unequivocally as genocide. Despite this, opposition groups and affected communities continue to express dissatisfaction with the vagueness of financial commitments and perceived inadequacy in addressing lasting impacts of the genocide.[20]

The Namibian government has plans to expand the Lüderitz port in order to facilitate mass production of “green hydrogen,” a proposed alternative to fossil fuels.[21] These plans were halted in 2024 amid traditional leaders’ concerns over disturbing the remains of genocide victims on Shark Island. Shark Island was used as a concentration camp during the genocide and is in close proximity to the Lüderitz port.[22] Planned expansion efforts include parts of Shark Island in port infrastructure.[23] For many genocide victims, the ocean around Shark Island serves as their final resting place. Traditional leaders are concerned that port construction efforts will disturb human remains and desecrate unmarked graves in the area, and they have called for archaeological investigations before further port development.[24] The Nama Traditional Authority (NTA), an association of traditional Nama leaders, was not consulted prior to drafting port expansion plans, and the NTA urges preservation of Shark Island as a sacred heritage site.

Written by Evelyn Middleton, April 2025.

To learn more about the genocide and efforts for reparations and justice, see the resources listed below.

Book: History and Analysis

Olusoga, David and Casper W. Erichson. The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism, Faber and Faber, 2011.

Sarkin, Jeremy. Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims Under International Law by the Herero Against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904-1908, Praeger Security International, 2009.

Sarkin, Jeremy. Germany’s Genocide of the Herero: Kaiser Wilhelm II, His General, His Settlers, His Soldiers, Boydell and Brewer, 2011.

Weiser, Martin. The Herero War- The First Genocide of the 20th Century? GRIN Verlag, 2008.

U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Did Germany’s Actions in the Herero Rebellion Constitute Genocide? CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014.

Books: Fiction

Kaye, E. J. This Is the Dead Land: A Novel of the Herero. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

Kubuitsile, Lauri. The Scattering. Penguin Random House South Africa, 2016.

Legal Cases

Hereros ex rel. Riruako v. Deutsche Afrika-Linien Gmblt & Co., 232 F. App’x 90 (3d Cir., 2007)

The Hereros v. Deutsche Afrika-Linien GMBLT & Co., No. CIV.A.05-1872(KSH), 2006 WL 182078, at *1 (D.N.J. Jan. 24, 2006)

Herero People’s Reparations Corp. v. Deutsche Bank AG, No. CIV. 01-01868 CKK, 2003 WL 26119014, at *1 (D.D.C. July 31, 2003)

Herero People’s Reparations Corp. v. Deutsche Bank AG, No. 03 CIV. 0991 (RLC), 2006 WL 903197, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 5, 2006)

Herero People’s Reparations et al. v. Federal Republic of Germany, 1:01cv0 1987

Herero People’s Reparation Corp. v. Deutsche Bank, A.G., 543 U.S. 987, 125 S. Ct. 508, 160 L. Ed. 2d 371 (2004)

Herero People’s Reparations Corp. v. Deutsche Bank, A.G., 370 F.3d 1192 (D.C. Cir. 2004)

News and Reports

“Republic of Namibia National Assembly Statement on the Genocide Related Issues,” Dr. Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila.

“Critical Appraisal of Saara Kuukongelwa-Amadhila Parliamentary Statement on German-Namibian Negotiations,” Dr. Freddy Omo Kustaa.

Letter to the Editor for “A Colonial-Era Wounds Open in Namibia,” Ngondi A. Kamatuka, January 2017.

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2015: Namibia.

“Documenting Violence Against Women, Even if It’s Hard to Look,” Aileen Jacobsen, March 2016.

“Drought Hits Namibia’s Poor the Hardest,” Al Jazeera, October 2013.

“Entire Tribe Killed: Germans Exterminate Natives of South West Africa,” The Daily East Oregonian, Amazon Digital Services, 2015.

“Forgotten Genocide: Namibia’s quest for Reparations,” Al Jazeera, August 2015.

“Genocide Negotiations Reopen Colonial Wounds In Namibia,” Al Jazeera, July 2016.

“Germany Grapples With Its African Genocide,” Norimitsu Onishi, New York Times, December 2016.

“Germany is sued in U.S. over early-1900s Namibia slaughter,” Jonathan Stempel, January 2017.

“Herero and Nama groups sue Germany over Namibia Genocide,” World Breaking News, January 2017.

“Namibia Spurns German Reparations,” Al Jazeera, November 2005.

“Namibia Genocide and the Second Reich.”

“Open Letter to the City of Hamburg and the People of Hamburg,” Ngondi A. Kamatuka, et al., January 2017.

“Pressure Grows on Germany in Legal Battle Over Colonial-Era Genocide,” DW, January 2018.

“The Leaders of Ovaherero and Nama Indigenous Peoples Announce the Filing of UN Complaints,” Africavenir, September 2016.

“The Troubling Origins of the Skeletons in a New York Museum,” Daniel A. Gross, The New Yorker, January 2018.

Articles

Anderson, Rachel, “Redressing Colonial Genocide Under International Law: The Hereros’ Cause of Action Against Germany,” California Law Review, Volume 93, Issue 4, pp. 1155-1190, 2005.

Carlson, Rachel, “Transitional Justice.”

Erickson, Sarah, “Human Rights in Namibia.”

Grofe, Jan, “Shadows of the Past: Chances and Problems for Herero in Claiming Reparations From Multinationals for Past Human Rights Violations,” The University of Western Cape, 2002.

Harring, Sidney L., “German Reparations to the Herero Nation: An Assertion of Herero Nationhood in the Path of Namibian Development,” West Virginia Law Review 393-417, Volume 104, Winter 2002; also in CUNY Academic Works, 2002, at http://academicworks.cuny.edu/cl_pubs/250

Kennedy, Ellen J., “China in Namibia.”

Kennedy, Ellen J., “Climate Change in Namibia.”

Markusen, Randi, “Botswana and a Legacy of Genocide.”

Nagiel, Svetlana Meyerzon, “An Overlooked Gateway to Victim Compensation: How States Can Provide A Forum for Human Rights Claims,” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 133, 2007.

Recommended Films

Namibia Genocide and the Second Reich, BBC Bristol, produced and directed by David Olusoga

One Hundred Years of Silence, Turbine Films

References

[1] Grotpeter, D. (2011, October 12). Colonialism and Imperialism in Africa. Encyclopedia of African History.

[2] Keegan, T. (2009, July 14). South African Control of Namibia, 1915-1990. Journal of African Studies.

[3] Lutz, D. (2003, March 16). The Herero and Nama Genocide: History and Context. Namibian Historical Studies.

[4] Guyer, R. (2016, February 22). The Uprising of the Herero and Nama, 1904-1908. African Conflict Journal.

[5] McKittrick, M. (2020, June 4). Extermination Orders and Colonial Violence in the Namibian Genocide. Journal of Genocide Research.

[6] Heffernan, A. (2007, July 18). The Omaheke Desert and the Genocide of the Herero. History Today.

[7] Zech, H. (2015, December 10). Medical Experimentation and the Aftermath of Genocide in Namibia. Journal of Historical Medicine.

[8] Kossler, K. (2013, September 5). The Impact of the Herero and Nama Genocide on Populations. The Namibian Heritage Journal.

[9] Norrington, J. (2018, August 3). The Berlin Conference and the Rise of German Colonial Rule. International Review of Historical Geography.

[10] Pott, A. (2012, November 15). German Colonial Policies in Namibia. Colonial Studies Journal.

[11] Stroud, C. (2018, October 29). The Vernichtungsbefehl and the Herero Genocide. Journal of European History.

[12] Ackermann, R. (2014, March 24). Shark Island: A Symbol of German Colonial Atrocities. Genocide Studies Journal.

[13] Fischer, A. (2011, January 10). The Herero-Nama Cultural Struggles under German Colonialism. African Anthropology and Sociology Review.

[14] Nhongo, K. (2024, June 28). Namibia plans to set up company for genocide victims’ descendants. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-06-28/namibia-plans-to-set-up-company-for-genocide-victims-descendants

[15] Connolly, K. (2023, April 28). UN representatives criticize Germany over reparations for colonial crimes in Namibia. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/apr/28/un-representatives-criticise-germany-over-reparations-for-colonial-crimes-in-namibia

[16] Ahmed, K. (2023, February 3). Descendants of Namibia’s genocide victims call on Germany to ‘stop hiding’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/feb/03/namibia-genocide-victims-herero-nama-germany-reparations

[17] Nyaungwa, N. (2024, March 7). Namibia’s communities demand return of land in dispute over German genocide legacy. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/namibian-communities-demand-return-land-dispute-over-german-genocide-legacy-2024-03-07/

[18] Oltermann, P. (2021, May 28). Germany agrees to pay Namibia €1.1bn over historical Herero-Nama genocide. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/28/germany-agrees-to-pay-namibia-11bn-over-historical-herero-nama-genocide

[19] Ahmed, K. (2023, February 3). Descendants of Namibia’s genocide victims call on Germany to ‘stop hiding’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/feb/03/namibia-genocide-victims-herero-nama-germany-reparations

[20] Africa Intelligence. (2025, March 6). Germany’s billion-euro fund to atone for Namibia genocide slow in coming. Africa Intelligence. https://www.africaintelligence.com/southern-africa-and-islands/2025/03/06/germany-s-billion-euro-fund-to-atone-for-namibia-genocide-slow-in-coming,110383379-art

[21] The Conversation. (2025, February 15). Namibia’s Shark Island: Europe’s push for green hydrogen risks compromising sites of colonial genocide. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/namibias-shark-island-europes-push-for-green-hydrogen-risks-compromising-sites-of-colonial-genocide-239549

[22] Prins, B. (2024, October 24). Traditional authority rejects Lüderitz port expansion plan. The Namibian. https://www.namibian.com.na/traditional-authority-rejects-luderitz-port-expansion-plan/

[23] Namundjembo, A. (2025, March 13). Lüderitz port dispute sparks heritage concerns. Windhoek Observer. https://www.observer24.com.na/luderitz-port-dispute-sparks-heritage-concerns/

[24] Prins, B. (2024, October 24). Traditional authority rejects Lüderitz port expansion plan. The Namibian. https://www.namibian.com.na/traditional-authority-rejects-luderitz-port-expansion-plan/