Cote d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast)

Where

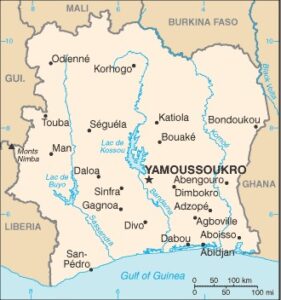

Côte D’Ivoire, or Ivory Coast, is in Western Africa and is bordered by Liberia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ghana. [3]

When

Côte d’Ivoire’s natural resources include cacao beans and diamonds.

A civil war occurred from 2004 to 2007 a that pitted northerners against southerners, Muslims against Christians, over issues of political control and access to Côte D’Ivoire’s diamond resources and territory.

A persistent challenge is widespread trafficking of women and children. Women and girls are trafficked internally and transnationally for domestic servitude, restaurant labor, forced street vending, and sexual exploitation. Boys are often trafficked as well, for agriculture, service labor, mining, construction, and in the fishing industry. [5] The children are forced to work in conditions with inadequate food, proximity to dangerous substances, and with no access to education or skill training.

Almost half of the world’s cocoa used in chocolate comes from Côte d’Ivoire,[13] which is the biggest producer of cocoa worldwide. Most of the laborers on cocoa plantations are between 12 and 16 years old, although some are as young as nine. Children do not receive any payment for their labor. They are also often beaten when they do not work or if they try to escape. Children are locked up at night, do not get sufficient nutrition, working 80 to 100 hours per week.

Most victims are children, 85% of them girls, who are trafficked into the country from Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, and Togo. [10] National armed forces and rebel groups also focus on recruiting children for armed conflict.

How

Human Trafficking

Human rights groups have charged that the Côte d’Ivoire government has done little to decrease or eliminate trafficking through either law enforcement efforts or the protection of likely sex trafficking victims.[7] Ivoirian law does not prohibit all forms of human trafficking, and Côte d’Ivoire has not ratified the 2000 United Nations Trafficking-In-Persons Protocol. [8] This results in a disconnect that allows for children to be trafficked and makes eliminating human trafficking in the region more difficult.

Sexual activity is perceived as a private matter, making communities reluctant to respond and intervene in cases of sexual exploitation, increasing children’s vulnerability, particularly through the belief that HIV/AIDS can be cured through sex with a virgin,[9] the availability of online child pornography, and sex tourism targeting children.[10]

Youth selling bananas on the roadside in Côte d’Ivoire. Image courtesy of Hanay is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The country’s cities and farms provide ample opportunities for traffickers. The informal labor sectors are not regulated under existing labor laws. Domestic workers, most non-industrial farm laborers, and those who work in the country’s street shops and restaurants remain outside government protection. [11]

Traffickers are often relatives or friends of the child victim’s parents, who sometimes promise parents that the children will learn a trade. However, the children often end up on the streets as vendors or as domestic servants. Many parents are financially desperate and hope that their own situation will improve because of what they expect will give their child a legitimate income.

Election-Based Violence and Civil War

In November 2010, the Ivory Coast held a long-postponed election where incumbent president Laurent Gbagbo faced challenger Alassane Ouattara. The votes were divided across regional and ethnic lines, with Gbagbo getting votes from primarily the south and west regions and Ouattara from the northern region. [1] Ouattara won this election that outside observers labeled free and fair, and this sparked the initial political crisis which escalated into widespread violence. Gbagbo refused to give up his office until he was arrested in May 2011. [2]

Map of Côte d’Ivoire. Image courtesy of The World Factbook is unmodified and is in the public domain.

This standoff resulted in large-scale violence throughout the country. Militias on both sides, launched attacks in several areas. It is estimated that over 3,000 people died, hundreds of women and girls were raped, and several hundred thousand Ivorians fled to neighboring Liberia for refuge, a post-conflict country ill-equipped to handle the situation. [3]

By May 2011, Ouattara successfully ousted Gbagbo, working to consolidate power, investigate and seek justice for atrocities committed during previous months. However, this justice was not impartial and sought to convict only pro-Gbagbo supporters who had committed crimes, even though atrocities had been committed on both sides. International actors condemned Gbagbo and his abuses but failed to condemn Ouattara’s abuses. [5]

Under Ouattara’s rule during the next few years, courthouses, prisons, and parliamentary elections were reestablished due to the conflict. Ouattara’s presidency resulted in many reconstruction efforts, done by implementing a Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) program—an effort to disarm and reintegrate 60,000 youths who had fought on both sides during the 2011 conflict. While this program officially ended in 2015, much of this disarmament was one-sided, benefiting pro-Ouattara forces. [6]

Throughout 2011 and 2012, the Ivorian military, under Ouattara’s governance, committed numerous human rights violations while attempting to quell security threats. These abuses included torture, killings, rapes, and extortion. Many individuals who had fled returned to find their land had been taken over through illegal sales or hostile occupations.

Former president Laurent Nbgagbo and former militia leader Charles Ble Goude were put on trial at the International Criminal Court in 2016 for crimes against humanity during the 2011 conflict. They were acquitted in 2019 due to insufficient evidence. The ICC indicted Simone Gbagbo, the former first lady, but the Ivorian government refused to transfer her to The Hague. Instead, Ivorian courts indicted her on crimes against humanity and war crimes. Human rights groups refused to participate in the trial due to apparent biases and flaws. In 2015 she was sentenced to 20 years in prison. However, in 2018 President Ouattara declared amnesty for crimes related to the post-election crisis. [9]

Today

Côte D’Ivoire continues to recover from this political crisis today. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), established in 2012 by President Ouattara, has been slow to effect change due to the depth of division between those who are being reintegrated and those who survived. [27] The TRC’s final justice and reparations report submitted to the president in December of 2014 was never fully implemented, continuing the failures of reintegration within Côte d’Ivoire. [28]

Côte d’Ivoire has increased security deployments of the military in the northern region in attempts to alleviate poverty and youth unemployment. There are concerns of multiple terrorist groups moving south from Africa’s Sahel region towards Côte d’Ivoire, including Boko Haram, al-Qaeda, and other smaller factions. The country has responded preemptively to these concerns, with a focus on security and socio-economic factors that may limit the group’s influence such as limiting their recruitment tactics by focusing on trade skills to give the youth employable skills.[29]

Regional tensions exist between Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso. In 2024, Burkina Faso accused Côte d’Ivoire of running operations to destabilize the country. Tensions on this issue continue. [23]

During his presidential terms, Ouattara has been criticized for human rights violations involving housing rights, freedom of expression, and treatment of marginalized communities. However, there continues to be little done regarding these violations.

Mass evictions, often using excessive force by law enforcement, occur in informal settlements in Abidjan, the economic capital of Côte d’Ivoire. [24]. Amnesty International documents that the evictions violated human rights standards because many residents were not given proper prior notice, alternative options for housing, or compensation.[25]

The LGBTQ+ community has experienced an increase in hate crimes in recent years. Human rights defenders call for an end to the violence against the community. The National Human Rights Council urged the public to reject violence against LGBTQ+ citizens; however, no effort has been made by the government to support this

Other human rights concerns come from limitations on freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly for opposition party supporters. In February 2023, the authorities arrested 31 activists from the African People’s Party-Côte d-Ivoire, resulting in 26 of the 31 being sentenced to two years in prison. While their sentences were suspended on appeal less than a month later, the use of authorities to jail opposition party support violates political rights. [30]

These human rights issues remain prevalent in Côte d’Ivoire with an upcoming presidential election in 2025.

Updated by Evelyn Middleton, October 2024.

References

[1] Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). World Report 2011: Côte d’Ivoire. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2011/country-chapters/cote-divoire

[2] BBC. (2021, April 13). Q&A: Ivory Coast crisis. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-11916590

[3] Akam, S. (2011, March 31). Liberia Uneasily Linked to Ivory Coast Conflict. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/01/world/africa/01liberia.html

[4] Brownsell, J. (2013, March 3). Kenya: What went wrong in 2007? Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/03/201333123153703492.html

[5] Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). World Report 2011: Côte d’Ivoire. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2011/country-chapters/cote-divoire

[6] Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). World Report 2016: Côte d’Ivoire. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2016/country-chapters/cote-divoire

[7] Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). World Report 2016: Côte d’Ivoire. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2016/country-chapters/cote-divoire

[8] Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). World Report 2017: Côte d’Ivoire. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/cote-divoire

[9] Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). World Report 2020: Côte d’Ivoire. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/cote-divoire

[10] Duhem, V. (2020, March 6). Alassane Ouattara pulls out of the 2020 presidential election. The Africa Report. https://www.theafricareport.com/24262/alassane-ouattara-pulls-out-of-the-2020-presidential-election/

[11] Britannica. (2024, October 25). Côte d’Ivoire. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Cote-dIvoire

[12] U.S. Department of State. (n.d.) Cote d’Ivoire. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2015/243421.htm

[13] Human Trafficking & Modern-day Slavery. (n.d.) gvnet. http://gvnet.com/humantrafficking/CoteD’Ivoire.htm

[14] U.S. Department of State. (n.d.) Trafficking in Persons 2015 Report: Country Narratives. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2015/243421.htm

[15] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (n.d.) Human Trafficking. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html

[16] Leclerc-Madlala, S. (2002). On the virgin cleansing myth: gendered bodies, AIDS and ethnomedicine. African Journal of AIDS Research, 1(2), 87-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25871812

[17] Human Trafficking & Modern-day Slavery. (n.d.) gvnet. http://gvnet.com/humantrafficking/CoteD’Ivoire.htm

[18] U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). 2005 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61565.htm

[19] Africa: Migrants, Slavery. (2021, May). Migration News, 8(5). https://migration.ucdavis.edu/mn/more.php?id=2377

[20] Human Trafficking ‘Unacceptable’, Says UK Confectionary Association. (2007, March 15). Christian Today. https://www.christiantoday.com/article/human.trafficking.unacceptable.says.uk.confectionary.association /9949.html

[21] Lamb, C. (2001, April 22). The child slaves of the Ivory Coast – bought and sold for as little as £40. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/cotedivoire/1317006/The-child-slaves-of-the-Ivory-Coast-bought-and-sold-for-as-little-as-40.html

[22] Ivory Coast’s Ouattara says he won’t seek third term in October election. (2020, May 3). France 24. https://www.france24.com/en/20200305-ivory-coast-s-ouattara-says-he-won-t-seek-third-term-in-october-election

[23] Crisis Group. (n.d.). Crisis watch conflict tracker. Crisis Watch. https://www.crisisgroup.org/crisiswatch

[24] Amnesty International. (2024, August 16). Thousands of evicted families awaiting support measures. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/08/Côte-divoire-thousands-of-families-still-awaiting-support-measures-after-forced-evictions-in-abidjan/#:~:text=The%20Ivorian%20authorities%20must%20immediately,potentially%20affected%2C%20said%20Amnesty%20International

[25] Mariem, S. B. (2024, August 16). Amnesty International calls for the implementation of support measures for evicted people in Ivory Coast. Jurist. https://www.jurist.org/news/2024/08/amnesty-international-calls-for-the-implementation-of-support-measures-for-evicted-people-in-ivory-coast/

[26] Presse, A.-A. F. (2024, September 5). LGBTQ activists in I. Coast concerned over wave of attacks. Barron’s. https://www.barrons.com/news/lgbtq-activists-in-i-coast-concerned-over-wave-of-attacks-c350fab4

[27] Al Jazeera England. (2021, March). Ivory Coast’s struggle to recover from political crisis. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mpgjvsw86Bw&t=3s

[28] Moody, J. (2021). Côte d’Ivoire: Peacebuilding in Côte d’Ivoire – why it is hard to reintegrate combatants and achieve justice – allafrica.com. AllAfrica. https://allafrica.com/stories/202105070323.html

[29] International Crisis Group. (2023, August). Keeping jihadists out of northern Côte d’Ivoire | Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/Côte-divoire/b192-keeping-jihadists-out-northern-Côte-divoire

[30] U.S. State Department. (2023). 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Côte d’Ivoire. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/Côte-divoire/#:~:text=In%20February%2C%20soon%20after%20Damana,protest%20the%20arrests%20across%20Abidjan