Burundi, 1972

Where

Burundi is a landlocked country in east-central Africa, bordered by Rwanda, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In 1972, Burundi’s population was estimated at 3.6 million. The country is composed of three ethnic communities: the Tutsis (14% of the population), the Hutus (85%), and the Twa (1%).

The Kingdom of Burundi dates back to the 1500s. Until colonization, Burundi’s ethnic groups enjoyed relatively equal positions in society. In 1890, the country was colonized by Germany, before being occupied by Belgium in 1916. Belgian colonizers established an ethnic power hierarchy to facilitate colonial rule. The Tutsi minority held power over the Hutu majority.

The Kingdom of Burundi dates back to the 1500s. Until colonization, Burundi’s ethnic groups enjoyed relatively equal positions in society. In 1890, the country was colonized by Germany, before being occupied by Belgium in 1916. Belgian colonizers established an ethnic power hierarchy to facilitate colonial rule. The Tutsi minority held power over the Hutu majority.

After regaining independence from colonial rule in 1962, the Tutsi minority maintained political and social power. This structure inspired resentment among many ethnic Hutus.

When

Hutu resentment of Tutsi rule became violent on April 29, 1972. Bands of Hutu radicals and Mulelists, Congolese exiles, led a Hutu uprising armed with poisoned machetes, clubs, automatic weapons, and gasoline bombs. Between 800 and 1,200 Tutsi civilians and some Hutu moderates were killed.

The Tutsi government, led by President Michel Micombero, reacted harshly to the insurrection. Within 24 hours, the government initiated a wave of brutal counterattacks. President Micombero called the violence a Hutu plot to exterminate all Tutsis, presenting a false death toll of 50,000 civilians. This was used to incite genocide by amplifying Tutsi fear that if they lost their dominant position in society, they would be exterminated by the Hutu majority.

How

In the four months following the Hutu insurrection, Tutsi government forces pursued a systematic campaign of genocide against all elite or educated Hutus. The leaders of the genocide were all Tutsi-Hima and part of the post-colonial ruling Parti de l’Union et du Progrès National.

These leaders sought to eliminate all Hutu threats to the Tutsi regime and to establish their power in the eyes of their rival Tutsi sub-group: the Tutsi-Banyaruguru. Their extermination campaign received support from the party’s violent youth wing, the Jeunesses Révolutionnaires Rwagasore (JRR). Many Tutsi civilians also joined the violence.

Tutsi soldiers abducted or killed all educated Hutus they could find, even school children. Hutu university students were often beaten to death by classmates. Hutu religious leaders, school directors, teachers, civil servants, some semi-skilled workers, and all Hutu politicians were beaten, shot, or imprisoned.

Response

By August 1972, almost all educated Hutu were dead or had fled to neighboring countries. The genocide claimed between 150,000 and 300,000 Hutu lives.

The Organization of African Unity, the United Nations, and the United States have been criticized for failing to intervene and curb the violence. UN relief was provided to displaced persons, but much of it was provided after the atrocities had subsided.

Today, few people know about the events of 1972. The atrocities were of little geopolitical interest to western powers, and Burundi’s authorities made every effort to deny entry to journalists after the genocide. In cases where the genocide has been remembered, western news has often mischaracterized the atrocities. Some of the minimal academic literature on the subject is poorly researched or analyzed.

Image by EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid| Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)| Copyright: EU/ECHO/Anouk Delafortrie| License

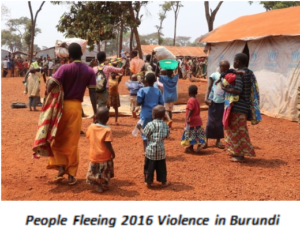

Nonetheless, the genocide contributed to lasting inter-ethnic distrust and to Burundi’s 12-year civil war. Scholar René Lemarchand even links the genocide to the birth of the Parti pour la Libération du Peuple Hutu (FNL); a radical party intent on stripping all power from the Tutsi minority. Today, Burundi is one of the poorest countries in the world and has recently suffered massive human rights violations under the leadership of former Hutu President Nkurunziza. International watch groups have raised alarms about renewed ethnic violence and the potential for another genocide in Burundi.

Updated 2021.

References

Image Sources

Burundi (29) – The World Factbook 2021. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2021. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/

People Fleeing 2016 Violence in Burundi (2) – EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/eu_echo/29969041886

Information Sources

“An Ambassador’s Reflections on a Bloodbath.” https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/100_for_100/003

“Burundi.” https://www.britannica.com/place/Burundi

“Burundi.” https://www.genocidewatch.com/burundi

“Burundian Time-Bomb.” https://www.economist.com/leaders/2016/04/23/burundian-time-bomb

“Burundi: Events of 2018.” https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/burundi

“Burundi Profile – Timeline.” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13087604

“For Burundi Gravedigger, Bodies and Memories Resurface as Mass Grave Exhumed.” https://www.reuters.com/article/us-burundi-mass-graves-idUSKBN1ZR1NF

Hinton, A.L., La Pointe, T., & Irvin-Erickson, D. Hidden Genocides: Power, Knowledge, Memory. Rutgers University Press, 2014.

Lemarchand, René. Forgotten Genocides: Oblivion, Denial and Memory. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

“Slaughter in Burundi: How Ethnic Conflict Erupted.” https://www.nytimes.com/1972/06/11/archives/slaughter-in-burundi-how-ethnic-conflict-erupted-slaughter-in.html

“The Burundi Killings of 1972.” https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/burundi-killings-1972.html

“Timelines Explorer – Data Commons.” https://datacommons.org/tools/timeline#&place=country/BDI&statsVar=Count_Person

Weinstein, Warren. “Review.” The Journal of Modern African Studies, 1976.