Native Americans

What

An estimated 10 million indigenous peoples were living in what is now the US when Christopher Columbus reached the Americas in 1492. By 1900, there were fewer than 300,000 Native Americans.[1]

European colonists massacred native people, forcibly removed tribes from their lands in deadly marches, and spread infectious diseases that the Native Americans had never faced and that devastated the Native population.

Where

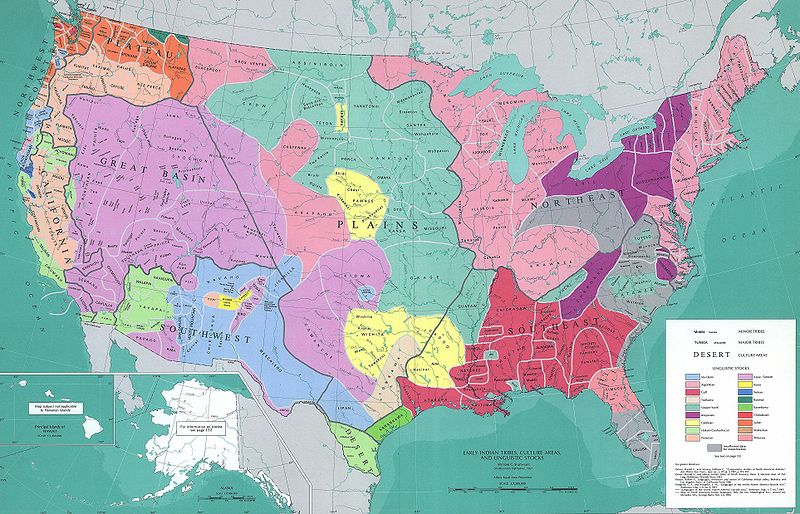

Native Americans belonged to social groups known as nations, or tribes, that spanned from present-day Canada to Central America. There were over 200 nations that spoke more than 200 different languages and had their own unique cultures.

When

Early Relations

Many Native American nations embraced the opportunity to trade with the European newcomers for goods they never had, including knives, axes, hoes, pots, guns, and horses. These goods allowed tribes to hunt and farm more efficiently and many welcomed European innovations. Native Americans had good relationships with some European powers, especially with the French, who came to the Americas in the 1530s to engage in fur trading.

The French respected indigenous territories, learned Native languages and customs, and treated Native Americans as trusted friends. The French established their first settlement in Quebec in 1608, the year after the English founded Jamestown in Virginia. The French settlement did not displace any Native Americans, who continued to work closely in the fur trade. Because of their close relationship, Native American nations often sided with the French in their conflicts with the English.

The initial contact between the English colonists and Native Americans was much different. When Jamestown was established in 1607, the settlers depended on the generosity of the Native Americans for their food and resources. This relationship was exploited by Captain John Smith, who began taking food by force, leading to violent conflict between the colonists and Native Americans.

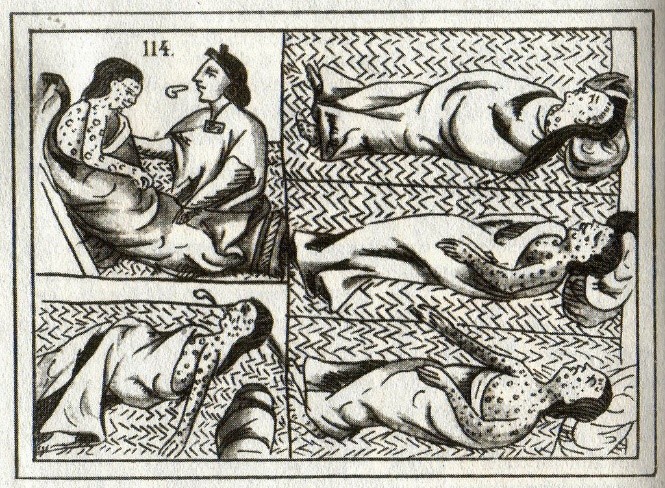

Disease

With the arrival of the Europeans came the arrival of diseases the Native Americans had never encountered: smallpox, bubonic plague, measles, influenza, diphtheria, and pneumonia, among others. European diseases devastated many nations, and explorers often found empty villages that had once been inhabited by Native Americans. When the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, they thanked God for finding land that was planted with corn just waiting for them. But it wasn’t God’s doing. From 1616 to 1619, around 90% of Native Americans in coastal New England were killed by diseases brought by rodents on trade ships.[2] Across North America, an estimated 11 million Native Americans perished between 1500 and 1900, mostly from diseases brought by Europeans.[3]

Early colonists saw the spread of disease among Native Americans as God’s plan for them to settle the area or as God’s wrath for the sinful life of Native Americans. Native Americans’ susceptibility to disease was also used against them. In 1832, Congress appropriated $12,000 to vaccinate Native Americans from smallpox, enough to vaccinate two-thirds of the country’s indigenous population. The Secretary of War chose which tribes received vaccinations and intentionally did not vaccinate Northern Plains nations as a way to weaken these tribes in their clashes with the U.S. military.[4]

The American Revolution and Beyond

Many Native American nations saw the colonists’ desire for westward expansion as a threat to their way of life, and tribes overwhelmingly supported the British during the American Revolution. The Cherokee, Creek, and most Iroquois nations provided critical support to the British war effort. However, no native representatives were present at the treaty negotiations that concluded the war in 1783. The British granted the new U.S. republic all land east of the Mississippi, which at that time was mostly inhabited by Native Americans.[5]

Three years later, the U.S. government and the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw nations signed the Treaty of Hopewell. It was the first attempt by the U.S. government to establish some hegemony over Native American nations. The treaty ceded over 69,000 acres of land in return for government protection and the return of property seized during the war.[6] The treaty also established the boundaries of the Native American nations, which covered about two-thirds of the present state of Mississippi.

Between 1784 and 1871, the government negotiated 377 treaties with various tribes. Many of these treaties ensured that Native American nations would not be removed from their lands. However, in 1800, Thomas Jefferson issued a military order to seize all lands bordering the Mississippi River for national defense. Jefferson knew that eventually the government would have to induce tribes to trade their ancestral lands for new lands west of the Mississippi and the treaties were repeatedly violated.[7]

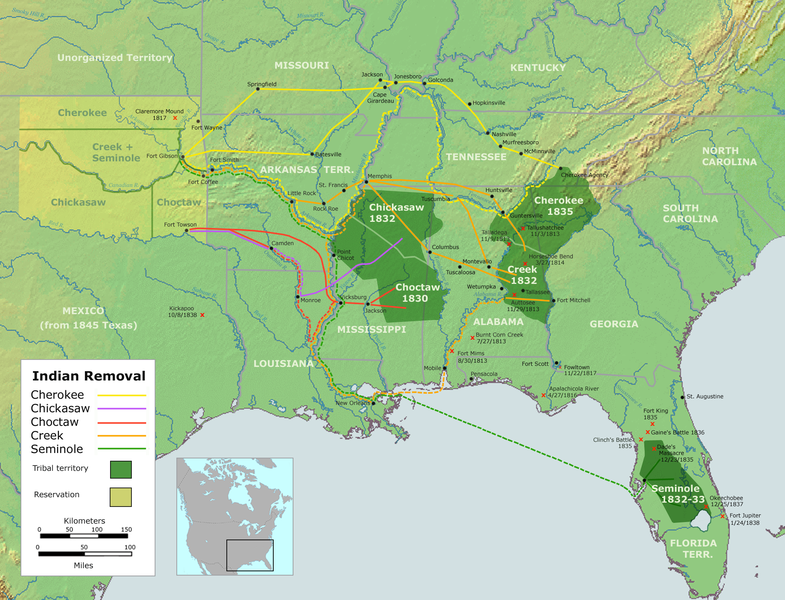

Removal

The Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations were known as America’s Five Civilized Tribes because of their quick and skillful adaptation to the “white man’s ways.” The U.S. government felt threatened by these tribes and saw them as a barrier to expansion.[8] Many scholars suggest that the Choctaw became one of the first targets for the federal government not only because they had valuable land that the government wanted, but also because they were a large, prestigious, and highly-successful nation. Ultimately, the Choctaw paid the price for their success, and they were the first Native American tribe to be removed by the government from their homeland to land set aside for them in present-day Oklahoma.

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson in 1830. The law authorized the president to grant tribes unsettled lands west of the Mississippi in exchange for Native American lands within the borders of the US. The Act promised Native Americans title to their land in the West, protection from trespass or attacks, and payment for the cost of relocation.[9] Jackson believed that tribes were unable to assimilate and that the demise of the Native American way of life was inevitable. He saw the Indian Removal Act as a humane policy and a generous act of mercy on behalf of the government.[10]

But the Act was far from humane and merciful. Thousands of Native Americans would perish on the journey west, known as the Trail of Tears. The Choctaw was the first nation expelled from their land in 1831. They made the journey on foot, some bound in chains, without food, supplies, or the help promised by the government. Thousands perished along the way. [11]

The removal process continued throughout the 1830s and was met with resistance by several tribes. When the Seminole nation refused to leave their land, the Second Seminole War ensued, lasting from 1835 to 1842 and costing thousands of lives and millions of dollars.[12]

The Creeks refused to leave but were forced out in 1836. Of the 15,000 Creeks who set out for Oklahoma, 3,500 died along the way. The Cherokee also refused to leave their land, and the nation’s chief, John Ross, protested the removal to Congress, presenting a petition with 16,000 Cherokee signatures. Congress approved the removal, but most of the Cherokee remained. The government sent 7,000 troops who forced the Cherokee into stockades at bayonet point. No one was allowed to gather their belongings before marching over 1,200 miles to Native American territory. Over 5,000 Cherokee perished on the journey.[13] By 1837, the Jackson administration had removed 46,000 Native Americans from their land, opening 25 million acres of land to white settlement and African slavery.[14]

Reservations

In 1851, Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act, creating the reservation system. Native Americans were once again forced to move. The U.S. government promised to support tribes with food and supplies, but these promises were often broken. Tribes were given unfertile land, and many nations that were once hunters struggled to become farmers.[15] Starvation and disease were common.

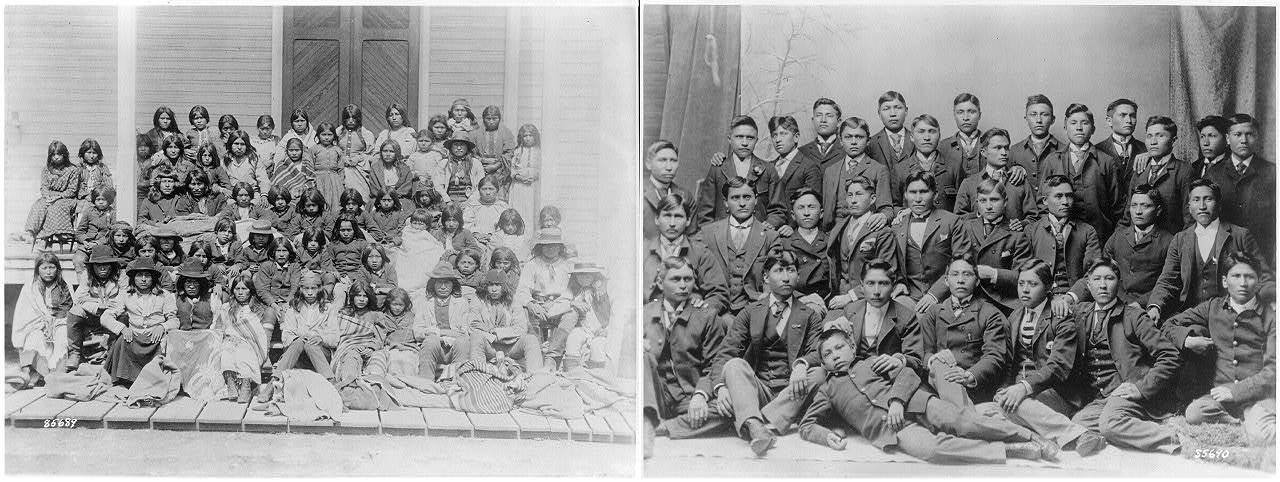

Chiricahua Apaches before and after boarding school Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Native Americans were encouraged or forced to wear American clothes, learn English, and convert to Christianity. Children were sent to boarding schools where they were forbidden to speak their tribal languages and were required to wear American clothes and cut their hair.[16] More information on the boarding schools can be found here.

In 1887, the Dawes Act or General Allotment Act was created to further encourage assimilation into American culture. Allotment converted tribal ownership of land into ownership by individuals. By doing this, Native Americans became subject to state authority rather than tribal authority, and tribal affiliations were often terminated.[17]

The reservation system soon became overtaken by allotment, and the consequences were detrimental to Native American nations. Allotment liquidated tribal power and decreased Native American lands by over half, opening up more land for white settlers. Even if their land was fertile, many Native Americans couldn’t afford the supplies needed to harvest.[18]

How

European diseases were most responsible for the massive decline in population. But fear, racism, and manifest destiny, the idea that U.S. expansion was destined by God, led the U.S. government to authorize over 1,500 wars, attacks, and raids on Native Americans, the most of any country in the world against indigenous people.[19] Massacres at Sand Creek and Wounded Knee, among the most notorious, took the lives of hundreds of Native Americans, many of them women and children. The largest mass execution in American history was perpetrated when President Abraham Lincoln ordered the hanging of 38 Dakota Sioux in Mankato, Minnesota in 1862.

Colonists used disease, removal, murder, and starvation to wipe out the Native population. One of the most detrimental efforts to Native Americans in the Plains region (from west of the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains) was the intentional destruction of the buffalo population, which the Plains nations depended on for survival. Buffalo provided food, shelter, clothing, weapons, and fuel and were spiritually significant to many tribes. At the beginning of the 19th century, buffalo numbered over 30 million. By the end of the 19th century, only a few hundred were left in the wild. One army colonel famously said, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”[20] The Plains tribes faced wide-scale starvation and social and cultural disintegration.

Attempts to eradicate Native American culture through boarding schools, allotment, and forced assimilation has had the most devastating and lasting consequences.

Response

20th Century

The 20th century was a time of progress for many Native American nations. Communities began rejecting allotment and assimilationist policies and advocating for better educational and economic opportunities. Several laws were passed that improved the conditions of Native Americans, including the Indian Citizenship Act, which passed in 1924 and gave Native Americans dual citizenship in their own nations and in the US.[21] Four years later, the Meriam Report was released. It gave an analysis of Native American living conditions and highlighted the detrimental effect the Dawes Act had on Native American nations.[22] The report influenced policies that improved healthcare, education, and land rights, ultimately leading to the creation of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), which passed in 1934.

The IRA halted individual allotment and returned some of the surplus land to the tribes. The IRA was designed so that Native Americans could exercise self-determination, spawn economic development, and maintain their culture. One of the most important aspects of the IRA was federal acknowledgement of tribal authority and self-government. Many nations started to reorganize and adopt constitutions establishing tribal governments, allowing them more independence from state governments.[23] In the decades to come, Native American nations began to take control of their schools, health-care facilities, social service programs, and legal and judicial systems.

The passing of the Indian Reorganization Act was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which gave Native Americans voting rights, and the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968, which established the right to free speech, the right to a jury, and protection from unreasonable search and seizure for Native Americans. [24]

Current Challenges

here are grave challenges affecting Native Americans today, including slow economic development, inadequate housing, efforts to diminish tribal sovereignty, high infant mortality rates and other health issues, and violence against women and girls. Native Americans have the highest poverty rate of any ethnic group in America, with 28% of the population below the poverty line.[25] That number is even higher on some reservations such as the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, where over 52% of the population lives in poverty, the highest percentage of any county in the US. A lack of economic opportunity on reservations has led to a 10% unemployment rate and has forced many Native Americans to leave the reservations in search of work.

Poverty and joblessness have caused a housing crisis among Native Americans. Currently, there are 90,000 homeless or under-housed Native American families. Nearly 40% of reservation housing is considered substandard, with 30% of homes facing overcrowding. Less than half of reservation housing is connected to a public sewer and 16% lack indoor plumbing.[26] It is not uncommon for three or more generations to live in a two-bedroom home with inadequate plumbing, kitchen facilities, cooling, and heating.

Native Americans also face several health concerns, including higher infant mortality rates, shorter life expectancy, and increased rates of suicide and alcoholism than other Americans.[27] Historical trauma and economic disadvantages have contributed to high rates of alcohol and drug abuse among many Native Americans, who are five times more likely to die from alcohol-related causes than white Americans. Native Americans have some of the highest rates of fetal alcohol syndrome in the nation.[28] Methamphetamine abuse has also increased in recent years. According to the Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, meth is fueling homicides, aggravated assaults, rape, child abuse, and other crimes.[29] According to the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, Native American and Alaska Native populations had the second highest overdose rates from all opioids in 2017 (15.7 deaths/100,000 population) among racial/ethnic groups in the US. [30]

Native American women also face epidemic levels of violence. Over 84% of Native women have experienced violence sometime in their lifetime. [35] Native American women are more likely to be sexually and physically assaulted than other women, and they make up an overwhelming percentage of sex trafficking victims.[31]. Although close to 90% of these crimes are perpetrated by non-Natives, a legal loophole prevents tribal governments from prosecuting non-Native individuals who commit crimes on reservations.[32] This jurisdictional problem allows white perpetrators to commit crimes against Native American women on reservations with almost-guaranteed impunity.

These high levels of violence, combined with low levels of prosecution, contribute to the epidemic of thousands of missing and murdered Indigenous women throughout the United States. Over the past few decades, thousands of Indigenous women are thought to have disappeared, but a lack of a single federal database tracking system makes these exact figures unknown. [36] Recently, various advocacy groups have helped these issues gain national attention, thereby leading to the drafting of important legislation. Specifically, Savanna’s Act is a bill that works to increase the coordination between federal, state, and tribal governments through a shared database and standardized protocol. The Not Invisible Act of 2019 calls for an advisory committee, composed of all three governmental levels, to create a report determining the root causes of the epidemic and improved responses. [37] Finally, the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (VAWA) had a section added to it specifically related to increasing the safety and protection of women in tribal communities. [36] As of early 2020, Savanna’s Act and VAWA are under review on the Congressional floor while the Not Invisible Act remains in committee. [38]

In 1977 the United Nations released a report prepared in conjunction with the Native American Solidarity Committee outlining the genocidal practices of the U.S. government, including the sterilization of Native American women. The report concluded that 24 percent of Native women had been sterilized and that 19 percent of the women were of child-bearing age [34]. Native American women were easier targets because of their greater social invisibility, smaller numbers, and laws that facilitated bureaucratic secrecy about the government’s sterilization policies. It took years of hearings, news reports, investigative analyses, and interviews with women to bring to light the scope of the individual, family, and tribal impact of forced sterilizations. More information about these forced sterilizations can be found here.

Although Native American nations face significant issues, they have also achieved great successes. The rapid expansion of Tribal colleges and universities (TCUs) is one of the most notable achievements. Since 1968, when the first TCU was founded, 35 accredited TCUs have opened in the US, serving more than 30,000 Native American students. Students learn about Native culture in addition to taking traditional courses like chemistry, engineering, and mathematics.[33] Many generous scholarships are available to Native students, making TCUs often the most affordable option. Initiatives like TCUs give Native American nations hope for a more prosperous and a culturally-vibrant future.

Future

Looking forward, with increases in reporting and the availability of information, awareness regarding the tremendous challenges Indigenous people face is rising. With the introduction of the Not Invisible Act, Savanna’s Act, and Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act in Congress, real progress is being made in helping to address these challenges. However, progress is not nearly as fast nor enough to make up for the inhumane treatment of Native Americans that have occurred throughout history and have resulted in the violence, poverty, and health epidemics these communities face today.

Updated April 2020.

References

[1] http://endgenocide.org/learn/past-genocides/native-americans/

[2] http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2012/11/leptospirosis_and_pilgrims_the_wampanoag_may_have_been_killed_off_by_an.html

[3] Guenter Lewy. “Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?” (History New Network, September 2004). http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/7302

[4] http://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/325

[5] https://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/native-americans-role-american-revolution-choosing-sides#sect-background

[6] Treaties with the Choctaws, The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (2011), http://www.choctaw.org/aboutMBCI/history/treaties1786.html

[7] Peter J. Ferrara, “The Choctaw Revolution: Lessons for Federal Indian Policy.”

[8] https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

[9] Matthew L. M. Fletcher, “Encyclopedia of United States Indian Law and Policy.” Michigan State University Press, 2012).

[10] H. W. Brands. “Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times.” Pgs. 489-493 (Anchor Books, 2006).

[11] https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

[12] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2959.html

[13] https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

[14] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2959.html

[15] https://www.history.com/topics/indian-reservations

[16] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/stories/articles/2015/5/25/how-american-indian-reservations-came-be/

[17] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/stories/articles/2015/5/25/how-american-indian-reservations-came-be/

[18] https://www.history.com/topics/indian-reservations

[19] https://www.history.com/news/native-americans-genocide-united-states

[20] https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349/

[21] http://endgenocide.org/learn/past-genocides/native-americans/

[22] https://www.history.com/topics/indian-reservations

[23] Peter J. Ferrara, “The Choctaw Revolution: Lessons for Federal Indian Policy.”

[24] http://endgenocide.org/learn/past-genocides/native-americans/

[25] http://www.nativepartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=naa_livingconditions

* http://www.woundsofwhiteclay.com/data/

[26] http://www.ncai.org/policy-issues/economic-development-commerce/housing-infrastructure

[27] https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/

[28] https://www.ihs.gov/headstart/documents/FetalAlcoholSpectrumDisordersAmongNativeAmericans.pdf

[29] https://www.rcfp.org/reporters-guide-american-indian-law/challenges-facing-american-indians

[30] http://humantraffickingsearch.org/traffickingofnativeamericans/

[31] https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/bnpb73/native-american-women-are-rape-targets-because-of-a-legislative-loophole-511