Yemen

What

An impoverished family in Taizz, Yemen. Image courtesy of Mathieu Génon from Paris / justdia.org is cropped and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

In 2010, Arab Spring protests, large pro-democracy demonstrations, swelled from North Africa to the Middle East, finally reaching Yemen. The Arab Spring movement intersected with Yemen’s unique political and economic circumstances and laid the foundation for a national uprising and subsequent revolution and civil war, which has caused international conflict and enduring violence.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has called the conflict in Yemen “the largest humanitarian crisis in the world.”[1] The World Food Program (WFP) currently feeds 12 million -Yemenis each month and has labeled Yemen’s hunger level as ‘unprecedented.’[2] The 2024 WFP Situation Report estimates that of a population of 33.7 million, 18.2 million Yemenis need humanitarian assistance (54%), 4.5 million people are internally displaced (13%), and another 17.6 million people are food insecure (52%).[3]

Where

Yemen borders Saudia Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast. The country also borders the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, and the Arabian Sea.[4]

Background

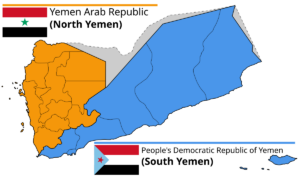

The Kingdom of Yemen was established in 1918 after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. In 1962, Arab nationalist revolutionaries overthrew the king and established the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen). Shortly after the British withdrew in 1967 from their adjacent colony in present-day southern Yemen, a Marxist government was formed and established the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen). Decades of hostility between North Yemen and South Yemen ensued, marked by inter- and intrastate conflict until the two countries were unified in 1990 as the Republic of Yemen.

Map of North and South Yemen. Image courtesy of Orange Tuesday is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

In the early 1990s, the Houthi movement, a Shi’a political and armed rebel group, emerged in northern Yemen.[5] Historically, Houthi interests had been sidelined by a majority Sunni government.[6] Sunni Muslims make up a majority of the religious demographic in Yemen, with 65% of the population being Sunni and 34% Shi’a.[6] War broke out between the Houthis and the Yemeni government and continued until a ceasefire was brokered in 2010.

In 2011, Arab Spring and other anti-government protests gained momentum in Yemen’s capital Sana’a and other major cities. Some protests became violent. In 2012, President Saleh stepped down in response to calls for his removal from power. His Vice President, Abd Rabuh Mansur Hadi, was elected president in an uncontested election.[7]

President Hadi convened a National Dialogue Conference (NDC) in 2013 to address political, constitutional, and social issues.[8] The Houthis felt that their interests were unrepresented in the NDC, forged an alliance with former President Saleh, and invaded the capital in 2014.[9]

President Hadi escaped from the Houthi-held capital in 2015 and fled to Saudi Arabia. Violence escalated into civil war between the Houthis and the exiled Hadi government. The conflict continues today and has led to broader regional and international conflicts.[10]

The Conflict

Causes of Violence

The ongoing conflict in Yemen stems from political, economic, and religious tensions. The conflict has been described as a regional proxy war with neighboring Saudia Arabia and allies who oppose the Houthi forces. It is believed that Houthi forces are receiving support from Iran.[11] The Saudi-led coalition that began targeting the Houthis with airstrikes in 2015 was comprised of Arab states including Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates.[12] These states participated in the bombing campaigns based on their respective relationships with Saudi Arabia, a regional powerhouse.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates buy U.S., British, and French weapons.[13] These trade relationships established lucrative financial incentives for the US and certain European nations to maintain the flow of arms, intelligence, and logistics support to the Saudi-led coalition.[14]

Saudi Arabia and the United States have strong geo-strategic interests in Saudi influence becoming entrenched in Yemen. Yemen is positioned to operate as a gatekeeper for Saudi Arabia’s maritime access to international shipping lanes. Iran controls Saudi Arabia’s access to maritime shipping routes at the other end of the Arabian Peninsula.[15] Therefore, Saudi influence in Yemen could ensure the continued flow of Saudi oil tankers to the international market.[16]

The Middle East has been facing increasing water scarcity. At current usage rates, Yemen will deplete its natural freshwater resources in approximately 50 years.[17] Resource scarcity fuels conflict in this region.

Methods of Violence and Crimes Perpetrated

Victims of Saudi-led airstrikes on a university in Dhamar, southwestern Yemen, 2019. Image courtesy of Felton Davis is unmodified and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Saudi-led coalition airstrikes have caused significant devastation in Yemen. While the airstrikes target combatant Houthi and other anti-government forces, many civilians have been killed or injured. Over 19,200 civilians have been maimed or killed from coalition airstrikes.[18] High civilian casualties raise concerns about the indiscriminate nature of these airstrikes and whether civilians are being targeted intentionally. Human Rights Watch documented 90 coalition airstrikes that hit critical civilian areas including hospitals, schools, markets, and mosques.[19] Airstrikes also destroyed important cultural heritage sites, including parts of Sana’a which were classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[20]

Ground and naval operations, led by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Morocco, and Egypt, have occurred in addition to airstrikes.[21]

Houthi forces have conducted indiscriminate artillery attacks, shelling and firing ballistic missiles in populated areas of Yemen and Saudi Arabia.[22] Houthi forces have taken hostages to extort money from or to exchange for their people held by opposing forces.[23] Both Houthi and coalition forces have used banned toxic weapons. Houthi forces deploy landmines despite Yemen being a signatory to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty.[24]

Efforts to Intervene

Support and resistance from Yemeni civil society has been ineffective, as infrastructure has been decimated and residents face widespread famine. Leaders including journalists, activists, lawyers, and rights defenders fear harassment, arrest, violence, and forced disappearances.[25]

International efforts for a ceasefire, led by the Gulf Cooperation Council, Arab League, and the United Nations, have been ineffective. Efforts to deliver humanitarian aid are routinely blocked by coalition restrictions on imports and by Houthi confiscations of food and medical supplies.[26] The UN has appointed a Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen, but the group’s remit is limited to monitoring and reporting.[27]

Today

The Houthis launched an offensive on Marib, a critical stronghold in 2021, that resulted in an increase in Saudi-led airstrikes. Despite continued urges for ceasefires and conflict resolution, violence continues in the region.[28]

In 2022 the UN truce agreement between the Houthi rebels and the internationally recognized government of Yemen lasted only six months.[29]

Regional geopolitical tensions create complex factors in international involvement in the region. Current Saudi-Iran reconciliation efforts have reduced some external influence. The Biden Administration also reduced U.S. involvement in the conflict, [30] and the UN has attempted to reignite temporary ceasefires.[31]

Any form of peace agreement must include safety for civil society to sustain positive peace.

Page written by Ryan Lins; updated by Evelyn Middleton, December 2024.

References

[1] United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (n.d.). Yemen crisis: What you need to know. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/yemen-crisis

[2] World Food Programme (WFP). (n.d.). Yemen emergency. WFP. https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/yemen-emergency

[3] World Food Programme (WFP). (2019, July). WFP Yemen Situation Report #49. WFP. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/1eea3b5abfb4482c995fb99d13a4f631/download/

[4] Center for Preventive Action (2024, October 8). Conflict in Yemen and the Red Sea. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/war-yemen

[5] Hoffman, V. J. (2019). Religion and politics in the Arab Spring and its aftermath. In V. J. Hoffman (Ed.), Making the New Middle East: Politics, culture, and human rights (p. 59). Syracuse University Press.

[6] United States Institute of Peace. (2022). Yemen, Religion, Peace and Conflict Country Profile. USIP. https://www.usip.org/programs/religion-and-conflict-country-profiles/yemen

[7] U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). (n.d.). The World Factbook: Saudi Arabia. CIA. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sa.html

[8] Reuters. (n.d.). U.S., France, Britain may be complicit in Yemen war crimes, U.N. report says. Reuters. https://ru.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1VO11B

[9] The Water Project. (n.d.). Water in crisis – Middle East. The Water Project. https://thewaterproject.org/water-crisis/water-in-crisis-middle-east

[10] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). (n.d.). Bachelet urges States with the power and influence to end starvation, killing of civilians in Yemen. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23855&LangID=E

[11] Krause, P. & Parker, T. (2020, March 26). Yemen’s proxy wars explained. MIT Center for International Studies. https://cis.mit.edu/publications/analysis-opinion/2020/yemens-proxy-wars-explained

[12] Human Rights Watch. (2016, July 11). Saudi Coalition Airstrikes Target Civilian Factories in Yemen. HRW. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/07/11/saudi-coalition-airstrikes-target-civilian-factories-yemen

[13] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). (2018, July 31). Special focus on coalition forces in the Middle East: The Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. ACLED. https://www.acleddata.com/2018/07/31/special-focus-on-coalition-forces-in-the-middle-east-the-saudi-led-coalition-in-yemen/

[14] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). (2019, June 18). Press release: Yemen war death toll exceeds 90,000 according to new ACLED data for 2015. ACLED. http://acleddata.com/2019/06/18/press-release-yemen-war-death-toll-exceeds-90000-according-to-new-acled-data-for-2015/

[15] Human Rights Watch. (2018, September 25). Yemen: Houthi hostage-taking – Arbitrary detention, torture, enforced disappearances go unpunished. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/09/25/yemen-houthi-hostage-taking

[16] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). (n.d.). Human Rights Council: Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/YemenGEE/Pages/Index.aspx

[17] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). (n.d.). Human Rights Council: Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/YemenGEE/Pages/Index.aspx

[18] Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. (2024, December 1). Yemen. Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. https://www.globalr2p.org/countries/yemen/

[19] Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). Yemen: Events of 2018. Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/yemen

[20] Hoffman, V. J. (2019). Religion and Politics in the Arab Spring and Its Aftermath. Syracuse University Press.

[21] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). (2018, July). Special Focus on Coalition Forces in the Middle East: The Saudi-led Coalition in Yemen. https://www.acleddata.com/2018/07/31/special-focus-on-coalition-forces-in-the-middle-east-the-saudi-led-coalition-in-yemen/

[22] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). (2019, June). Press Release: Yemen War Death Toll Exceeds 90,000 According to New ACLED Data for 2015. https://acleddata.com/2019/06/18/press-release-yemen-war-death-toll-exceeds-90000-according-to-new-acled-data-for-2015/

[23] Human Rights Watch (HRW). (2018, September). Yemen: Houthi Hostage-Taking – Arbitrary Detention, Torture, Enforced Disappearances Go Unpunished. https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/09/25/yemen-houthi-hostage-taking

[24] Human Rights Watch (HRW). (2019). Yemen: Events of 2018. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/yemen

[25] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). (n.d.). Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen. Human Rights Council. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/YemenGEE/Pages/Index.aspx

[26] Human Rights Watch. (2017, September 27). Yemen: Coalition’s Blocking Aid, Fuel Endangers Civilians. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/27/yemen-coalitions-blocking-aid-fuel-endangers-civilians

[27] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). (n.d.). Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen. Human Rights Council. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/YemenGEE/Pages/Index.aspx

[28] Robinson, K. (2023, May 1). Yemen’s Tragedy; War, Stalemate, and Suffering. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/yemen-crisis

[29] Britannica. (2024, December 9). Yemen. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Yemen

[30] Concern Worldwide (2024, April). The crisis in Yemen, explained: 5 things to know in 2024. Concern Worldwide. https://www.concern.org.uk/news/yemen-crisis-explained

[31] Al Obahi, L. (2024, September 12). UN Security Council Briefing on Yemen by Linda Al Obahi. Working Group on Women, Peace and Security. https://www.womenpeacesecurity.org/resource/un-security-council-briefing-yemen-linda-alobahi/