India

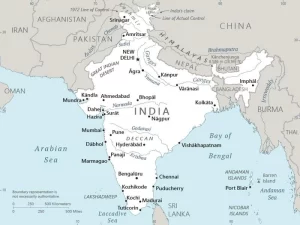

India is the world’s largest democracy and the country with the world’s largest population, housing 1.3 billion people, of whom about 80% are Hindu and 14% Muslim. [1] Despite the constitutional requirement of secularism, discrimination continues against Muslims [2] and other minorities, such as Kuki Christians and Dalit people.

The Rise of Hindu Nationalism in India

In 1947, India became independent from England and drafted its constitution. Secularism is a key element of this constitution, protecting freedom of religion, allows religious groups to oversee their own affairs, and bars taxes on non-adherents for religious causes. [3] This model of secularism, however, does not fully separate religion and state. The state, for instance, controls Hindu religious institutions and can regulate activity “associated with religious practice.” [4] Thus, the Indian government may provide funding for religious schools, finance religious buildings, or apply laws regarding marriage, divorce, and more based on religion. [5]

Some groups have challenged India’s secularism. In particular, Hindu nationalists maintain that Hinduism is the core component of Indian identity, and they have sought to enforce this through political means. [6]

In 1951, Hindu nationalists formed the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) party in collaboration with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) group, a right-wing, pro-Hindu party. The current ruling Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) traces its roots to the BJS and to this far-right collaboration, and the BJP promotes Hindutva, an ideology which seeks “to define Indian culture in terms of Hindu values.” [7] In the 1980s, the BJP supported the demolition of the Muslim Babri Mosque to be replaced with a Hindu temple in a sacred Hindu area called Ayodhya. After leading the destruction of the mosque in 1992, the BJP rose to political prominence. [8]

Factions in the BJP target Muslims as the source of all Hindus’ troubles. Currently, the BJP is led by Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India. In speeches Modi has vowed to protect the interests of India’s minorities, but his actions appear to demonstrate an anti-Muslim bias. [9]

In 2002, when Modi was the Chief Minister of the western Indian state of Gujarat, there were three days of sectarian violence and riots. Violence continued for three months in Ahmedabad, the largest city in Gujarat, with disturbances against the Muslim population throughout the state continuing for the next year. [10] Modi and the BJP party were accused of inciting Hindu mobs against Muslims and condoning the violence. Modi was investigated by a Special Investigation Team formed by India’s Supreme Court, and he was ultimately cleared for his role. However, he was denied a visa to enter the US in 2005 due to his likely support of Hindu extremists during these riots. [11] In 2022, he approved the premature release of 11 men imprisoned for gangraping a pregnant Muslim woman and killing 14 of her family members during the riots, despite international and domestic condemnation. [12]

In 2023, the BBC released the documentary India: the Modi Question, an examination of Modi’s role in the Gujarat riots and subsequent anti-Muslim Indian policies. The Modi government suppressed the film, banning it inside India and pressuring social media companies to remove it from their platforms. [13] This follows other efforts at censorship by BJP officials, including the targeting of rival politicians for criticizing Modi and his political supporters. [14]

Modi became the face of the BJP in 2014 when he was elected Prime Minister of India. He promised great economic growth and played on sentiments of Hindu pride and hyper-nationalism, similar to the nationalist trend that was sweeping many countries around the world at the time. [15] India’s economy has seen strong growth since 2014 and is expected to continue growing at a consistent pace in the coming years. [16] But GDP growth remains low when compared to its historical improvement in India, and Modi uses his reputation as an economic talent to counter criticism of his other policies. [17]

Since Modi’s rise to power, multiple human rights organizations have noted increases in anti-Muslim sentiment, hate crimes, and legislation. One statistical analysis discussed by Scroll.in found that approximately 90% of religious hate crimes between 2009 and 2018 occurred under Modi’s government. [18] Research from the India Hate Lab revealed a 62% increase in anti-Muslim hate speech in the second half of 2023, with 413 separate incidents documented. [19] Illustratively, since 2020, Islamophobic actors have spread the conspiracy theory that Muslims caused and purposefully spread COVID-19. [20] Several government actions, alongside communal incidents, have raised concerns from these entities about anti-Muslim animus in India and its potentially genocidal impacts.

Hate Music

A central feature of the Hindutva movement, which maintains that India is a Hindu country to the exclusion of people of other faiths, is anti-Muslim discrimination in nearly all sectors of public life: housing, employment, education, legal access, health care, etc.

Hindutva is spread through many sources, one of which is through popular music. South Korea has K-pop, a non-ideological global music phenomenon. India has H-pop, the music and poetry of Hindu nationalism.

Hindutva is spread through many sources, one of which is through popular music. South Korea has K-pop, a non-ideological global music phenomenon. India has H-pop, the music and poetry of Hindu nationalism.

H-pop singers’ anti-Muslim hits have reached hundreds of millions on WhatsApp and YouTube, “turning obscure activists into nationwide celebrities,” according to Cultural Capital. [136] The journal reports, for example, that singer Laxmi Dubey, a onetime local journalist from northern India, has nearly 500,000 subscribers on YouTube and her biggest song has been played over 65 million times.

Sample lyrics include “In front of Hindu lions, the enemy will crumble. India would be of Hindus only, saffron [the red color associated with Hinduism] would fly high.” [137]

In an NPR interview, Kunal Purohit, author of a book on the rise of Hindu nationalist music, says the songs seem designed “to constantly create a level of anger and a level of fear among Hindus about Islam and the Muslim community in India. Hindutva pop is part and parcel of almost every hate speech event in India today.” [138]

Anti-CAA banners hang in New Delhi, 2020. Image courtesy of DiplomatTesterMan is cropped and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Citizenship Amendment Act

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) was passed by the Indian Parliament in 2019. Prior to the CAA, to be eligible for Indian citizenship, individuals must have lived in India for at least 11 years or worked for the federal government. [21] The CAA amends this law for members of certain religions. If refugees arrive in India from Pakistan, Bangladesh, or Afghanistan who are Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, or Christian, they are eligible for citizenship within only six years of Indian residency. [22] But this reduced waiting period does not apply to Muslim refugees. [23] The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stated that the law is “fundamentally discriminatory” and “undermines the commitment to equality before the law enshrined in India’s constitution.” [24] Modi and the BJP claim the law is necessary to help persecuted minorities who are living in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. [25] If this were accurate, however, persecuted minorities such as the Ahmadi Muslims in Pakistan and the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar would be included in the law, and they are not. [26]

There were wide-scale protests against the law that stymied its implementation for years. Then in March 2024, the Indian government issued regulations that operationalized the law. [27] Citizenship applications have been accepted and approved since then. [28] Muslim minority groups remain excluded from entering India, even as persecution of Muslims such as the Hazara in Afghanistan continues, and they need to find safe haven. [29]

2020 Delhi Riots

Peaceful protests against the CAA blanketed India following its announcement in 2019. [30] BJP officials used incendiary rhetoric to describe these protesters; for example, Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur called on those attending a BJP rally to, in reference to anti-CAA demonstrators, “shoot ‘traitors to the country.’” [31]

Destruction at the Wire Market in Gokal Puri after the Delhi Riots. Image courtesy of Banswalhemant is cropped and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Delhi, India’s capital territory, saw mass violence accompany these protests. On February 23, 2020, after a BJP speech demanding an end to anti-CAA advocacy, mobs of Hindu people formed and began assaulting Muslims across Northeast Delhi. [32] Rioters demolished mosques, burned homes, and firebombed businesses. [33] They beat and shot Muslims and physically attacked journalists. [34] Crowds shouted Hindutva slogans and bore Hindu nationalist symbols during their attacks. [35] Some Muslims retaliated, and many fled the city, finding refuge in outlying camps. [36] Violence lasted for several days, killing as many as 40 Muslims and 13 Hindus. [37] Hindu gangs roamed Delhi for weeks after, intimidating Muslim residents. [38] Some analysts labeled the riots a “pogrom,” a word originally used to describe anti-Jewish riots by Cossacks in tsarist Russia. [39]

A citizens’ committee led by former Indian federal judges deemed the government’s response to the riots inadequate. [40] The federal government did not send the army to quell rioting, despite calls for intervention by Delhi politicians. [41] Local police delayed their response to reports of violence, aided mobs by ignoring help calls from Muslim areas, stood by as attacks happened, and participated in assaults themselves. [42] Officers arrested political dissidents and students for protesting the CAA or reporting on the riots under India’s anti-terrorism law. [43] According to Human Rights Watch, irregularities mar current investigations into the event, with police disregarding court orders and shoddily handling evidence. [44] An inquiry into a video of several policemen brutalizing Muslim men has repeatedly been stalled. [45] According to Citizen Matters, tensions within Delhi remain high as of 2024, with families vigilant for future violence. [46]

Other violence against Muslims followed these 2020 outbreaks. In 2023, local officials in Haryana, a northern India state, demolished Muslim homes, claiming they were illegally built. [47] Courts eventually ordered the destruction to stop. Mobs lynched several Muslims in 2024. [48] In 2024, clashes between Hindu and Muslim communities broke out across the country due to Hindu nationalist marches, leading to attacks on Muslims, Muslim-owned businesses and homes, and mosques. [49] A Human Rights Watch investigation found that BJP leadership perpetuated hate speech against Muslims throughout the 2024 election season; Modi, for instance, repeatedly called Muslims “infiltrators.” [50]

Women have become targets for this growth in anti-Muslim violence. State schools have banned female students from wearing the hijab, denying them entrance if they do so, and women who don the hijab report harassment from Hindu mobs. [51] Several states in India have passed anti-conversion laws that restrict individuals trying to convert to Islam, Christianity, or other non-Hindu religions, stigmatizing these faiths and bolstering hate speech against Muslim men that frames them as committing “love jihad”—seducing Hindu women to forcibly convert them to their belief system. [52] Anti-Muslim activists have created online auction sites that put prominent Muslim women, ranging from film stars to social activists, up for “sale,” inciting violent, misogynistic rhetoric against them and prompting fears for their safety. [53] At some Hindutva rallies, speakers have exhorted Hindu men to “rape and impregnate Muslim women if Muslim men cast even a glance at Hindu girls”; this reflects how various Hindutva leaders frame rape as a political strategy. [54]

Removing Citizenship in Assam State

Assam is a state in northeast India with a population of 30 million people, one-third of whom are Muslim. [55] In the early 20th century, the British encouraged Bengali Muslim immigration into Assam for labor. As a result, the size of the Muslim population in Assam expanded greatly. [56]

When India and Pakistan were partitioned into two separate countries in 1947, Pakistan became a largely Muslim-dominated country and India predominantly Hindu. The state of Assam was given to India and became controlled by Hindus, despite the large Muslim population. [57] Muslims experienced violence in the 1960s and 1970s and Hindus labeled them illegal immigrants. [58] Anti-Muslim prejudice grew over the next few decades, and sporadic violence erupted between Muslims and non-Muslims in Assam into the 2000s. [59]

In 2013, the Indian Supreme Court ordered the state of Assam to complete an update for the National Registry of Citizens (NRC) to clarify who was, and who was not, a legal citizen. [60] The Supreme Court defined an illegal immigrant to be “anyone who cannot prove that they or their ancestors entered the country before midnight of March 24, 1971. [They will] be declared a foreigner and face deportation.” [61] Individuals had to submit evidence proving their relationship to listed individuals.

However, 28% of Assam’s population is illiterate; in addition, it is customary in this region that births and marriages often are not registered. [62] These obstacles resulted in authorities stripping citizenship from many individuals who have never lived outside of India and whose families for past generations have also never lived outside of India. [63]

In 2019, the final NRC was released and 1.9 million people were omitted from the citizenship register. [64] These people had 120 days to prove their citizenship by appealing to the Foreigner Tribunals in Assam. [65] However, Amnesty International maintains that these tribunals are arbitrary. [66] Despite promises that alleged foreigners would get notice of their exclusion, many people were not notified and were unaware that they were being considered for deportation. [67] Additionally, the judges presiding over the trials testify that they are hired on contracts that will not be renewed unless they “brand enough people as foreigners.” [68] Finally, the tribunals appear to discriminate. A survey found that “nearly nine-tenths of cases were against Muslims and almost 90% of those Muslims were declared illegal immigrants.” [69] People who are labeled ‘foreigners’ by the courts are placed in detention centers in Assam where they can be held for years. [70]

It is important to note that many Bengali Hindus were also left off the list and are placed in detention camps with Bengali Muslims. [71] These individuals who have lost their citizenship are now stateless, meaning that they have no rights that a nation guarantees to its citizens, including equality, freedom, and rights against exploitation.

Just days before the NRC was released, the BJP changed their public statements from supporting the NRC to calling it error ridden. [72] Observers have attributed this change to how many of the Bengali Hindus rendered stateless by the database were BJP supporters. [73] After the NRC’s release, Dilip Kumar Paul, a BJP legislative leader in Assam, said that they can “never accept this NRC where illegal Bangladeshi Muslims have been included” and that “Hindus can never be foreigners in India.” [74]

The NRC adjudication process is ongoing, and government investigations have found significant errors within the database. [75] Regardless, Assam’s leadership has pressed for more measures targeting “illegal immigrants,” and other Indian states have proposed compiling NRCs like that in Assam. [76]

Revoking Autonomy in Jammu and Kashmir

After the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan, the region of Jammu and Kashmir on the border of Pakistan retained a unique autonomous status. After nearly 75 years, however, the region was stripped of its autonomy in 2019. Its citizens, the majority of whom are Muslim, are now under armed government control.

There have been three wars between India and Pakistan and several armed skirmishes over this land. India controls 45% of the land, Pakistan 35%, and China the remaining 20%. [77] The lines between the Pakistani and Indian regions are separated by a heavily militarized cease-fire line called the Line of Control. [78] Armed Kashmiri groups have battled against the Indian government in the region for decades. [79] While India labels them Pakistan-sponsored terrorists, they see themselves as freedom fighters, working toward eventual independence from the state or possible unification with Pakistan. [80]

The Indus River is a vital water resource to the region, Karakouram Highway, Pakistan. Image courtesy of Joonas Lyytinen is licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

The conflict over Jammu and Kashmir occurs on religious and ideological grounds, and, crucially, over water resources within the Indus River System. [81] Two of the five Indus River tributaries run through Jammu and Kashmir. India and Pakistan rely heavily on the river to sustain agriculture and hydropower in their communities. Pakistan fears India will cut off their water supply if the Line of Control becomes an official border. [82] This happened in 1948 before an agreement was reached in the Indus Water Treaty. [83] Water scarcity would deeply disturb Pakistan’s economic and social lifelines. India consistently maintains that it has never tampered with Pakistan’s flow of water aside from minor mistakes during a short period of time. [84] However, Modi is currently fast-tracking hydropower projects worth $15 billion on the river despite Pakistan’s claims that this activity will disrupt its water supply. [85]

Since the BJP won national elections in 2014, tensions and violence have increased throughout Jammu and Kashmir. [86] There have been attacks and accusations from both sides, but on August 5, 2019, Modi revoked a constitutional provision that, since the mid-1900s, gave Kashmir the autonomy to make its own laws. [87] One day earlier, on August 4, Modi sent tens of thousands of Indian troops into the Jammu and Kashmir region. Modi also invoked a region-wide blackout, cutting off phone signals and the internet. [88] Authorities detained thousands of people, including children, and arrested dissenters. [89] Arrests of journalists and human rights defenders continue today, and military forces have killed several. [90]

Although blackout restrictions were eased in January 2020, Jammu and Kashmir have officially lost their autonomous statehood status and are under the same laws as other Indian territories. This move by the BJP violated the constitution and further evoked tensions in an already unstable region. [91] While the state’s citizenry elected a regional government in 2024, it lacks the autonomy previously held by Kashmir and is kept under federal oversight. [92] Several political parties have dedicated themselves to restoring the region’s previous status, but the BJP remains unyielding. [93]

Ethnic Violence in Manipur

Manipur is a northeastern Indian state known for its ethnic diversity. Various groups in Manipur have fought for greater autonomy since India’s independence. This conflict has resulted in thousands of deaths over the decades and continues today. [94] Meitei, a Hindu ethnic group, comprise most of Manipur’s population along with the Kuki-Zo (Kuki), a Christian community. [95] India’s Constitution labels the Kuki a “Scheduled Tribe,” a designation for the country’s disadvantaged groups that gives them access to affirmative action measures and special civil rights protections. [96]

In May 2023, violence erupted between the Meitei and Kuki over this classification scheme. The Manipur High Court ordered the state to recommend the Meitei’s categorization as a “Scheduled Tribe” to the national government. [97] Kuki and other minority groups protested the order, fearing it would enable further displacement from their homelands and limit socio-economic opportunities. [98] These protests led to greater ethnic violence. Meitei crowds roamed Manipur’s capital, Imphal, attacking and killing Kuki. Kuki militants kidnapped Meitei villagers and killed others. [99] Hundreds died. [100] Mobs burned hundreds of churches and temples, thousands of homes, and two local synagogues. [101] Video evidence emerged in July 2023 of egregious public sexual assaults of Kuki women by male mobs—the women had sought police protection, but officers handed them over to the crowd. [102]

Years of anti-Kuki rhetoric preceded these attacks, with Meitei state officials and civilians labeling them drug traffickers and criticizing their status as a “Scheduled Tribe.” [103] N. Biren Singh, leader of Manipur’s government, a member of the BJP, and a Meitei himself, blamed the Kuki for the violence. [104] Kuki accuse Manipur police of aiding Meitei mobs and ignoring Kuki reports of violent crimes. [105]

An inadequate government response followed the riots. The state cut off internet access and imposed curfews. [106] Tens of thousands of internally displaced persons live in makeshift camps with few necessities. [107] Strict segregation also developed, with Meitei and Kuki largely living in separate parts of the state divided by buffer zones. [108] Prime Minister Modi did not speak about the situation for months, only doing so once video evidence was released. He has not yet visited the state. [109]

Conflict persists. Reports from 2024 describe mob attacks against Kuki and Meitei and multiple deaths. [110] Soldiers from both collectives wage war against each other, often using weapons stolen from police armories. [111] Peace negotiations and reconciliation efforts have emerged and continue, but mistrust remains high. [112] In addition, Meitei politicians attempted to strip some Kuki groups of their “Scheduled Tribe” status, thus provoking further tension. [113] Beyond the Kuki, other Christian communities, like those in New Delhi, have reported violence from Hindu nationalists and called for greater protections for them. [114]

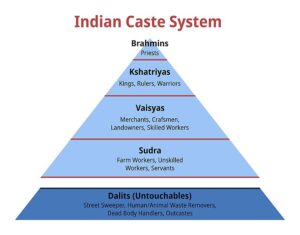

Caste Discrimination

In India, the caste system—a social structure which classifies individuals into hierarchical groups based on their birth—serves as a means of societal organization. [115] Under it, a person’s caste determines their economic, educational, and social opportunities, with upper castes garnering greater ones. [116] The institution fosters discrimination, as castes segregate themselves from each other and upper castes dominate those below them. [117] Some communities even punish intermarriage and interaction between castes. [118] Dalits are the lowest caste, and they are deeply persecuted and limited in their socio-economic advancement. [119]

Image courtesy of Giveaway285 is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Caste organization originated before colonization, but the British turned it into a rigid colonial tool, solidifying its societal place. [120] India’s post-independence legislature outlawed discrimination based on caste in 1948 and incorporated that ban into its Constitution in 1950. [121] The government also established affirmative action programs for Dalits and other marginalized groups. [122] Since then, the situation for lower castes inside the country has improved. However, pervasive prejudice and discriminatory violence persist against them, and upper castes control most of the nation’s resources.

Mobs frequently attack Dalit communities, often due to Dalit advocacy for greater rights. [123] And Dalits might be subjected to violence just by interacting across caste lines. In 2022, for example, a teacher killed nine-year-old Indra Meghwal, a Dalit, for drinking from a pot meant for upper castes. [124] Abusers target Dalit for sexual violence; one government survey found that ten Dalit women are raped every day in India. [125] When survivors bring court cases against perpetrators, survivors face institutional hurdles, particularly police apathy and judicial delays. [126] Discrimination against Dalit people pervades fields ranging from healthcare to temple access to wages. [127] Programs meant to uplift rural residents exclude Dalits, and some government policies target them for population control measures, painting them as poverty spreaders. [128] some upper-caste individuals allegedly poured human feces into the water supply of a Tamil Nadu Dalit community in 2022, resulting in serious illness. [129] Dalit endure countless other indignities.

Future

In 2024, India held general parliamentary elections. While polling predicted a massive BJP victory, actual voting resulted in the party’s defeat, with it earning 240 seats, far short of the 272 needed to form a government. [130] The BJP’s wider political coalition, however, did win enough seats to constitute a majority, and Modi remains the country’s Prime Minister. [131] Analysts have linked this loss to voter discontent with the BJP’s anti-Muslim policies, inflammatory rhetoric, and perceived failings in preventing increased unemployment and other economic issues. [132] Indian Muslims viewed the outcome as a respite from persecution and argued that it points to the unpopularity of Hindutva ideology among India’s wider population. [133]

Yet many of the BJP’s past policies continue today, and the party recently won state elections in Haryana by surprise. [134] And Muslims still face violence from nationalist societal elements. Other groups, like Christians, experience similar oppression. Conflict in Manipur endures, and lower caste peoples, principally Dalits, encounter widespread discrimination.

But local and global advocacy groups, like Hindus for Human Rights, have developed to challenge the BJP, its treatment of India’s minorities, and its Hindutva propaganda. International organizations, like the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, have raised concerns about India’s current climate, and in 2024, the United Holocaust Memorial Museum listed the country as the fifth most at risk of mass atrocities. [135]

Updated by Bekir Hodzic, October 2024.

References

[1] Central Intelligence Agency (2024, October 3). India. The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/india/

[2] Maizland, L. (2024, April 28). A history of the marginalization of India’s Muslim population. PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/a-history-of-the-marginalization-of-indias-muslim-population; Genocide Watch. (2024, September 30). The Ten Stages of Genocide in India – Part One. Genocide Watch. https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/the-ten-stages-of-genocide-in-india

[3] Katrak, M., & Kulkarni, S. (2021). Unravelling the Indian Conception of Secularism: Tremors of the Pandemic and Beyond. Secularism and Nonreligion, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.5334/snr.145

[4] Acevedo, D. D. (2013). Secularism in the Indian Context, Law & Soc. Inquiry, 38(1), 138. https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/81; Katrak, M., & Kulkarni, S. (2021). Unravelling the Indian Conception of Secularism: Tremors of the Pandemic and Beyond. Secularism and Nonreligion, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.5334/snr.145

[5] Acevedo, D. D. (2013). Secularism in the Indian Context, Law & Soc. Inquiry, 38(1), 138. https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/81; Katrak, M., & Kulkarni, S. (2021). Unravelling the Indian Conception of Secularism: Tremors of the Pandemic and Beyond. Secularism and Nonreligion, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.5334/snr.145

[6] Jaffrelot, C. (2019, April 4). The Fate of Secularism in India. In M. Vaishnav (Ed.), The BJP in Power: Indian Democracy and Religious Nationalism. Carnegie Endowment for Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2019/04/the-bjp-in-power-indian-democracy-and-religious-nationalism#the-fate-of-secularism-in-india

[7] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, October 8). Bharatiya Janata Party. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bharatiya-Janata-Party

[8] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, October 8). Bharatiya Janata Party. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bharatiya-Janata-Party

[9] Ayyub, R. (2019, June 28). What a Rising Tide of Violence Against Muslims in India Says About Modi’s Second Term. Time. https://time.com/5617161/india-religious-hate-crimes-modi/

[10] Ayyub, R. (2019, June 28). What a Rising Tide of Violence Against Muslims in India Says About Modi’s Second Term. Time. https://time.com/5617161/india-religious-hate-crimes-modi/

[11] Tisdall, S. (2016, June 2). Narendra Modi’s US visa secure despite Gujarat riots guilty verdicts. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/02/narendra-modis-us-visa-secure-despite-gujarat-riots-guilty-verdicts

[12] India’s Modi government approved release of Bilkis Bano’s rapists. (2022, October 18). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/10/18/indias-modi-government-approved-release-of-bilkis-banos-rapists

[13] Syed, A. (2023, January 26). India Banned a BBC Documentary Critical of Modi. Here’s How People Are Watching Anyway. Time. https://time.com/6250480/bbc-modi-documentary-skirting-censors/

[14] Hussain, A. & Saaliq, S. (2024, April 15). In Modi’s India, opponents and journalists feel the squeeze ahead of election. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/india-election-democracy-modi-hindu-nationalism-8f22465a6f0f021d43105a06a71d7840

[15] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, October 8). Bharatiya Janata Party. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bharatiya-Janata-Party

[16] Is India’s economy slowing down? (2024, October 10). The Economist. https://www.economist.com/asia/2024/10/10/is-indias-economy-slowing-down

[17] Chowdhury, D. R. (2024, April 24). How India’s Economy Has Really Fared Under Modi. Time. https://time.com/6969626/india-modi-economy-election/

[18] Ayyub, R. (2019, June 28). What a Rising Tide of Violence Against Muslims in India Says About Modi’s Second Term. Time. https://time.com/5617161/india-religious-hate-crimes-modi/; Mander, H. (2018, November 13). New hate crime tracker in India finds victims are predominantly Muslims, perpetrators Hindus. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/901206/new-hate-crime-tracker-in-india-finds-victims-are-predominantly-muslims-perpetrators-hindus

[19] Singh, K. (2024, February 26). Anti-Muslim hate speech soars in India, research group says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/anti-muslim-hate-speech-soars-india-research-group-says-2024-02-26/

[20] Frayer, L. (2020, April 23). Blamed For Coronavirus Outbreak, Muslims In India Come Under Attack. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/23/839980029/blamed-for-coronavirus-outbreak-muslims-in-india-come-under-attack

[21] CAA: India’s new citizenship law explained. (2024, March 12). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-50670393; India: Act No. 57 of 1955, Citizenship Act, 1955. (n.d.). Refworld. https://www.refworld.org/legal/legislation/natlegbod/1955/en/19544

[22] CAA: India’s new citizenship law explained. (2024, March 12). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-50670393

[23] CAA: India’s new citizenship law explained. (2024, March 12). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-50670393

[24] Slater, J. (2019, December 19). Why protests are erupting over India’s new citizenship law. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/why-indias-citizenship-law-is-so-contentious/2019/12/17/35d75996-2042-11ea-b034-de7dc2b5199b_story.html

[25] Slater, J. (2019, December 19). Why protests are erupting over India’s new citizenship law. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/why-indias-citizenship-law-is-so-contentious/2019/12/17/35d75996-2042-11ea-b034-de7dc2b5199b_story.html

[26] CAA: India’s new citizenship law explained. (2024, March 12). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-50670393

[27] India: Citizenship Amendment Act is a blow to Indian constitutional values and international standards. (2024, March 14). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/03/india-citizenship-amendment-act-is-a-blow-to-indian-constitutional-values-and-international-standards/; Bhattacharyya, R. (2024, March 25). Why Assam Is up in Arms Against Controversial New Indian Citizenship Law. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2024/03/why-assam-is-up-in-arms-against-controversial-new-indian-citizenship-law/

[28] Ahmad, T. (2024, June 3). India: Government Begins Implementing Controversial Citizenship Amendment Act. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2024-06-02/india-government-begins-implementing-controversial-citizenship-amendment-act/#:~:text=On%20May%2015%2C%202024%2C%20the,fleeing%20persecution%20in%20the%20region

[29] India: Citizenship Amendment Act is a blow to Indian constitutional values and international standards. (2024, March 14). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/03/india-citizenship-amendment-act-is-a-blow-to-indian-constitutional-values-and-international-standards/

[30] Human Rights Watch. (2020, April 9). “Shoot the Traitors”: Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/04/10/shoot-traitors/discrimination-against-muslims-under-indias-new-citizenship-policy#:~:text=Some%20have%20described%20the%20protesters,air%20near%20the%20protest%20site

[31] Iyer, K. (2022, October 11). Delhi Riots: How BJP Leaders Created A Powderkeg That Led To 2020 Hindu-Muslim Violence. Article 14. https://article-14.com/post/delhi-riots-how-bjp-leaders-created-a-powderkeg-that-led-to-2020-hindu-muslim-violence–6344d8d280625

[32] Gettleman, J., Raj, S. & Yasir, S. (2020, February 26). The Roots of the Delhi Riots: A Fiery Speech and an Ultimatum. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/26/world/asia/delhi-riots-kapil-mishra.html

[33] Mosque set on fire during Delhi’s worst violence in decades. (2020, February 26). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/2/26/mosque-set-on-fire-during-delhis-worst-violence-in-decades

[34] Barton, N. (2020, February 25). Delhi Violence: An Eyewitness Account From Jaffrabad. The Wire. https://thewire.in/communalism/ground-report-war-zone-in-north-east-delhi; Journalists harassed, attacked while covering Delhi riots. (2020, March 6). Committee to Protect Journalists. https://cpj.org/2020/03/at-least-12-journalists-harassed-attacked-amid-del/

[35] Delhi Violence 2020. (2020, November 1). The London Story. https://thelondonstory.org/report/delhi-violence-2020/

[36] Pal, A. & Ghoshal, D. (2020, March 4). Delhi’s displaced scrape a living after deadly riots. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/delhis-displaced-scrape-a-living-after-deadly-riots-idUSKBN20R2FU/

[37] India: Biased Investigations 2 Years After Delhi Riot. (2022, February 21). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/02/21/india-biased-investigations-2-years-after-delhi-riot

[38] Gettleman, J., Yasir, S., Raj, S. & Kumar, H. (2021, September 15). How Delhi’s Police Turned Against Muslims. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/12/world/asia/india-police-muslims.html

[39] Kamdar, M. (2020, February 28). What Happened in Delhi Was a Pogrom. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/02/what-happened-delhi-was-pogrom/607198/

[40] Scroll Staff. (2022, October 7). Delhi riots: Centre’s response to violence was wholly inadequate, says citizens’ committee. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/latest/1034499/delhi-riots-centres-response-to-violence-was-wholly-inadequate-says-citizens-committee

[41] Gunasekar, A., Sengar, M. S., Shukla, S. & Prabhu, S. (2020, February 25). 13 Dead In Delhi Clashes, 70 Have Gunshot Wounds: 10 Points. NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/delhi-violence-over-caa-northeast-delhi-tense-day-after-5-killed-in-caa-clashes-amid-donald-trump-vi-2185146; Serhan, Y. (2020, March 2). India Failed Delhi. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/india-modi-hindu-muslim-delhi-riots/607315/

[42] Gettleman, J., Yasir, S., Raj, S. & Kumar, H. (2021, September 15). How Delhi’s Police Turned Against Muslims. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/12/world/asia/india-police-muslims.html

[43] India: Biased Investigations 2 Years After Delhi Riot. (2022, February 21). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/02/21/india-biased-investigations-2-years-after-delhi-riot

[44] India: Biased Investigations 2 Years After Delhi Riot. (2022, February 21). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/02/21/india-biased-investigations-2-years-after-delhi-riot

[45] The Wire Staff (2024, July 23). Delhi Riots: HC Orders CBI Probe into Death of Muslim Man Beaten, Forced to Sing National Anthem. The Wire. https://thewire.in/law/delhi-riots-hc-orders-cbi-probe-into-death-of-muslim-man-beaten-forced-to-sing-national-anthem

[46] Bhargavi, J. (2024, May 29). The trials of a school in Northeast Delhi in the aftermath of the 2020 riots. Citizen Matters. https://citizenmatters.in/anatomy-of-a-riot-recovery-how-a-school-in-northeast-delhi-rebuilt-itself-after-the-2020-riots/

[47] Jafri, A. (2023, August 7). Muslim homes, shops bulldozed; over 150 arrested in Nuh in India’s Haryana. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/7/vengeance-muslim-homes-shops-bulldozed-150-arrested-in-indias-haryana

[48] Sharma, Y. (2024, June 25). ‘Eid means mourning’: Muslims lynched in India after shock election result. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/6/25/eid-means-mourning-muslims-lynched-in-india-after-shock-election-result

[49] India: Violence Marks Ram Temple Inauguration. (2024, January 31). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/01/31/india-violence-marks-ram-temple-inauguration

[50] India: Hate Speech Fueled Modi’s Election Campaign. (2024, August 14). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/08/14/india-hate-speech-fueled-modis-election-campaign

[51] Saaliq, S. (2022, February 8). Some students barred from class in India for wearing hijab. PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/some-students-barred-from-class-in-india-for-wearing-hijab; Hijab verdict: India Supreme Court split on headscarf ban in classrooms. (2022, October 13). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63225351; Outrage after hijab-wearing woman heckled by Hindu mob in India. (2022, February 8). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/8/schools-ordered-shut-in-india-as-hijab-ban-protests-intensify

[52] Frayer, L. (2021, October 10). In India, boy meets girl, proposes — and gets accused of jihad. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/10/10/1041105988/india-muslim-hindu-interfaith-wedding-conversion

[53] Yasir, S. (2022, January 3). Online ‘Auction’ Is Latest Attack on Muslim Women in India. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/03/world/asia/india-auction-muslim-women.html

[54] Asthana, N. C. (2022, February 12). Sadhvi Vibhanand’s Call to ‘Rape’ Muslim Women With Impunity Shows Hindutva’s Politics of Fear. The Wire. https://m.thewire.in/article/communalism/sadhvi-vibhanands-call-to-rape-muslim-women-with-impunity-shows-hindutvas-politics-of-fear/amp; Ashraf, A. (2016, May 28). Reading Savarkar: How a Hindutva icon justified the idea of rape as a political tool. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/808788/reading-savarkar-how-a-hindutva-icon-justified-the-idea-of-rape-as-a-political-tool

[55] Assam Population 2011-2019 Census. (n.d.). Census 2011 India. https://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/assam.html

[56] H. Srikanth. (2000). Militancy and Identity Politics in Assam. Economic and Political Weekly, 35(47), 4117–4124. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4409978

[57] Weiner, M. (1983). The Political Demography of Assam’s Anti-Immigrant Movement. Population and Development Review, 9(2), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1973053

[58] Monirul Hussain. (2000). State, Identity Movements and Internal Displacement in the North-East. Economic and Political Weekly, 35(51), 4519–4523. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4410084

[59] Mahr, K. (2012, August 13). India Continues to Grapple with Fallout from Assam Violence. Time. https://world.time.com/2012/08/13/india-continues-to-grapple-with-fallout-from-assam-violence/

[60] Dev, A. (2019, August 31). India Is Testing the Bounds of Citizenship. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/08/india-citizenship-assam-nrc/597208/

[61] Chakravarty, I. (2019, July 15). Explainer: What exactly is the National Register of Citizens? Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/930482/explainer-what-exactly-is-the-national-register-of-citizens

[62] Assam Population 2011-2019 Census. (n.d.). Census 2011 India. https://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/assam.html; Dev, A. (2019, August 31). India Is Testing the Bounds of Citizenship. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/08/india-citizenship-assam-nrc/597208/

[63] Saaliq, S. & Ganguly S. (2023, April 26). As India grows, so do demands for some to prove citizenship. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/india-citizenship-population-assam-38e6932b88902d9dd2715ae3373a2d91

[64] Eyre, M. & Nation Contributor. (2019, September 10). Why India Just Stripped 1.9 Million People of Citizenship. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/assam-national-register-citizens/

[65] India excludes nearly 2 million people from Assam citizen list. (2019, August 31). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/8/31/india-excludes-nearly-2-million-people-from-assam-citizen-list

[66] Amnesty International India. (2019). Designed to Exclude: How India’s Courts Are Allowing Foreigners Tribunals To Render People Stateless In Assam. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.be/IMG/pdf/rapport_inde.pdf

[67] Amnesty International India. (2019). Designed to Exclude: How India’s Courts Are Allowing Foreigners Tribunals To Render People Stateless In Assam. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.be/IMG/pdf/rapport_inde.pdf

[68] Dev, A. (2019, August 31). India Is Testing the Bounds of Citizenship. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/08/india-citizenship-assam-nrc/597208/; Mohan, R. (2019, July 30). ‘Worse than a death sentence’: Inside Assam’s sham trials that could strip millions of citizenship. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/932134/worse-than-a-death-sentence-inside-assams-sham-trials-that-could-strip-millions-of-citizenship

[69] Mohan, R. (2019, July 29). Inside India’s Sham Trials That Could Strip Millions of Citizenship. Vice. https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/3k33qy/worse-than-a-death-sentence-inside-indias-sham-trials-that-could-strip-millions-of-citizenship

[70] Chakravarty, I. (2019, July 15). Explainer: What exactly is the National Register of Citizens? Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/930482/explainer-what-exactly-is-the-national-register-of-citizens

[71] Assam NRC: What next for 1.9 million ‘stateless’ Indians? (2019, August 31). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-49520593

[72] Dutta, P. K. (2019, September 3). Assam NRC: Why BJP is upset and protesting over its own agenda. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/news-analysis/story/assam-nrc-why-bjp-is-upset-and-protesting-over-its-own-agenda-1594560-2019-09-02

[73] Zaman, R. (2024, March 15). ‘Betrayal by BJP’: Why CAA rules might not help Hindu Bengalis left out of Assam NRC. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/1065208/betrayal-by-bjp-why-caa-rules-might-not-help-hindu-bengalis-left-out-of-assam-nrc; Hazarika, M. (2019, November 22). ‘Hindus aren’t our enemies’ — why final NRC is not what BJP promised and envisioned. The Print. https://theprint.in/theprint-essential/hindus-arent-our-enemies-why-final-nrc-is-not-what-bjp-promised-and-envisioned/324713/

[74] Loiwal, M. (2019, August 31). NRC final list: BJP worried over exclusion of Hindus, inclusion of illegal Bangladeshi Muslims. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/nrc-final-list-bjp-worried-over-exclusion-of-hindus-inclusion-of-illegal-bangladeshi-muslims-1593966-2019-08-31

[75] Karmakar, S. (2024, March 13). ‘Finish the NRC process first’: NRC left outs in Assam confused, angry over the CAA rules. Deccan Herald. https://www.deccanherald.com/india/assam/finish-the-nrc-process-first-nrc-left-outs-in-assam-confused-angry-over-the-caa-rules-2935531#google_vignette

[76] “Just A Matter Of Time”: Governor On NRC In Manipur. (2024, July 4). NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/governor-on-nrc-in-manipur-just-a-matter-of-time-6020359

[77] Purohit, K. (2019, August 12). Will China fully support Pakistan on Kashmir? DW. https://www.dw.com/en/how-far-will-china-go-to-support-pakistans-position-on-kashmir/a-49993550

[78] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, October 8). Kashmir. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Kashmir-region-Indian-subcontinent

[79] Hussain, A. (2024, October 16). Kashmir gets a largely powerless government 5 years after India stripped its special status. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/kashmir-india-local-government-election-5dcdaa11a39c822459a9cb551c0e1db0

[80] Hussain, A. (2024, October 16). Kashmir gets a largely powerless government 5 years after India stripped its special status. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/kashmir-india-local-government-election-5dcdaa11a39c822459a9cb551c0e1db0

[81] Center for Preventative Action. (2024, April 9). Conflict Between India and Pakistan. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-between-india-and-pakistan

[82] Haines, D. (2023, February 23). India and Pakistan Are Playing a Dangerous Game in the Indus Basin. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/02/india-and-pakistan-are-playing-dangerous-game-indus-basin

[83] Haines, D. (2023, February 23). India and Pakistan Are Playing a Dangerous Game in the Indus Basin. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/02/india-and-pakistan-are-playing-dangerous-game-indus-basin

[84] Kashmir and the politics of water. (2011, August 1). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2011/8/1/kashmir-and-the-politics-of-water

[85] Reuters. (2017, March 16). Troubled waters? India fast-tracks hydro projects worth $15 billion in Kashmir. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/troubled-waters-india-fast-tracks-hydro-projects-worth-15-billion-in-disputed-kashmir/story-Z2ZNtwemuhAl5JVGyZpndN.html

[86] Fareed, R. (2021, August 5). Two years of Kashmir unrest, political void and a sinking economy. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/5/kashmir-special-status-india-two-years-human-rights-economy

[87] Reuters. (2017, March 16). Troubled waters? India fast-tracks hydro projects worth $15 billion in Kashmir. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/troubled-waters-india-fast-tracks-hydro-projects-worth-15-billion-in-disputed-kashmir/story-Z2ZNtwemuhAl5JVGyZpndN.html

[88] Regan, H. (2019, October 31). India downgrades Kashmir’s status and takes greater control over contested region. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/31/asia/jammu-kashmir-union-territory-intl-hnk/index.html

[89] Regan, H. (2019, October 31). India downgrades Kashmir’s status and takes greater control over contested region. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/31/asia/jammu-kashmir-union-territory-intl-hnk/index.html

[90] Vijayan, S. (2023, August 30). India Has Killed Off the Remains of Kashmir’s Free Press. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/world/india-kashmir-walla-free-press/; 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: India. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/india/

[91] Regan, H. (2019, October 31). India downgrades Kashmir’s status and takes greater control over contested region. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/31/asia/jammu-kashmir-union-territory-intl-hnk/index.html

[92] Khandekar, O. & Hadid, D. (2024, September 18). In Kashmir, voting begins in first local elections since India revoked autonomy. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/09/18/g-s1-23576/kashmir-election-india; Hussain, A. (2024, October 16). Kashmir gets a largely powerless government 5 years after India stripped its special status. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/kashmir-india-local-government-election-5dcdaa11a39c822459a9cb551c0e1db0

[93] Party opposed to India’s stripping of Kashmir’s autonomy wins election. (2024, October 8). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/8/party-opposed-to-indias-stripping-of-kashmirs-autonomy-wins-election

[94] Human Rights Watch. (2008, September 29). “These Fellows Must Be Eliminated”: Relentless Violence and Impunity in Manipur. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/09/29/these-fellows-must-be-eliminated/relentless-violence-and-impunity-manipur

[95] Why ethnic violence in India’s Manipur has been going on for three months. (2023, August 9). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/9/why-ethnic-violence-in-indias-manipur-has-been-going-on-for-three-months

[96] Leth, S. (2023, December 21). Understanding the complex conflict unfolding in Manipur. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Work_Group_for_Indigenous_Affairs

[97] Rathore, S. (2023, August 1). Navigating the Kuki-Meitei Conflict in India’s Manipur State. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2023/08/navigating-the-kuki-meitei-conflict-in-indias-manipur-state/

[98] India: Wanton killings, violence, and human rights abuses in Manipur. (2023, July 12). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa20/6969/2023/en/

[99] India: Authorities ‘missing-in-action’ amid ongoing violence and impunity in Manipur state – New testimonies. (2024, July 16). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/07/india-authorities-missing-in-action-amid-ongoing-violence-and-impunity-in-manipur-state-new-testimonies/

[100] India: Authorities ‘missing-in-action’ amid ongoing violence and impunity in Manipur state – New testimonies. (2024, July 16). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/07/india-authorities-missing-in-action-amid-ongoing-violence-and-impunity-in-manipur-state-new-testimonies/

[101] Ali, Y. (2023, September 9). The Manipur Crisis in Numbers: Four Months of Unending Violence. The Wire. https://thewire.in/security/the-manipur-crisis-in-numbers-four-months-of-unending-violence; 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: India. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/india/

[102] Kuthar, G. (2023, July 20). Outrage in India over video of Manipur women paraded naked, raped. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/7/20/outrage-in-india-over-video-of-manipur-women-paraded-naked-raped

[103] India: Renewed Ethnic Violence in Manipur State. (2024, September 14). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/09/14/india-renewed-ethnic-violence-manipur-state

[104] India: Renewed Ethnic Violence in Manipur State. (2024, September 14). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/09/14/india-renewed-ethnic-violence-manipur-state

[105] India: Authorities ‘missing-in-action’ amid ongoing violence and impunity in Manipur state – New testimonies. (2024, July 16). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/07/india-authorities-missing-in-action-amid-ongoing-violence-and-impunity-in-manipur-state-new-testimonies/

[106] Hussain, Z. & Jain, R. (2023, September 29). Indian protesters try to storm home of Manipur chief minister. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-imposes-curfew-strife-hit-areas-manipur-state-2023-09-28/

[107] Konnur, M. (2024, August 8). Waiting for peace in Indian state divided by violence. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz9delg2y1ro

[108] Konnur, M. (2024, August 8). Waiting for peace in Indian state divided by violence. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz9delg2y1ro

[109] The Associated Press. (2023, July 21). India’s Modi breaks silence on ethnic violence in Manipur after video shows women being paraded naked. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/indias-modi-breaks-silence-ethnic-violence-manipur-video-shows-women-p-rcna95467; Why is Modi ‘steadfastly refusing’ to visit Manipur: Congress jabs PM over Laos visit. (2024, October 10). The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/why-is-modi-steadfastly-refusing-to-visit-manipur-congress-jabs-pm-over-laos-visit/articleshow/114121061.cms?from=mdr

[110] Agarwala, T. (2024, September 7). Ethnic violence in India’s Manipur escalates, six killed. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/ethnic-violence-indias-manipur-escalates-six-killed-2024-09-07/

[111] The Wire Staff. (2024, May 3). Year After Manipur Violence Broke Out, Many Looted Arms Yet to Reach State Armouries. The Wire. https://thewire.in/security/year-after-manipur-violence-broke-out-many-looted-arms-yet-to-reach-state-armouries/?mid_related_new

[112] Konnur, M. (2024, August 8). Waiting for peace in Indian state divided by violence. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz9delg2y1ro

[113] Zaman, R. (2024, January 21). Explained: The demand to strip the Kuki-Zo communities of Scheduled Tribe status in Manipur. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/1062349/explained-the-demand-to-strip-the-kuki-zo-communities-of-scheduled-tribe-status-in-manipur

[114] 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom: India. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/india/

[115] What is India’s caste system? (2019, June 19). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-35650616

[116] Goghari, V. M., & Kusi, M. (2023). An introduction to the basic elements of the caste system of India. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1210577. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1210577

[117] Goghari, V. M., & Kusi, M. (2023). An introduction to the basic elements of the caste system of India. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1210577. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1210577

[118] The couples on the run for love in India. (2019, April 13). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-47823588

[119] The Dalit: Born into a life of discrimination and stigma. (2021, April 19). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2021/04/dalit-born-life-discrimination-and-stigma

[120] Chakravorty, S. (2019, June 18). Viewpoint: How the British reshaped India’s caste system. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-48619734

[121] Saxena, A. (2023, May 18). Should Caste Be a Protected Class? : An Assessment of the Arguments to Outlaw Caste Discrimination in America. Syracuse Law Review. https://lawreview.syr.edu/should-caste-be-a-protected-class-an-assessment-of-the-arguments-to-outlaw-caste-discrimination-in-america/

[122] Biswas, S. (2019, January 9). Is affirmative action in India becoming a gimmick? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-46806089

[123] Dalits in India. (n.d.). Minority Rights Group. https://minorityrights.org/communities/dalits/

[124] Chatterji, S. A. (2022, August 20). The Tragic Story of Indra Meghwal. The Citizen. https://www.thecitizen.in/india/haryana-assembly-campaign-in-high-gear-1068924?infinitescroll=1

[125] Singh, A. (2022, June 8). India: Why justice eludes many Dalit survivors of sexual violence. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/8/india-why-justice-eludes-many-dalit-survivors-of-sexual-violence#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20National%20Crime,day%20in%20India%2C%20on%20average

[126] Justice Denied: Sexual Violence & Intersectional Discrimination – Barriers To Accessing Justice For Dalit Women And Girls In Haryana, India. (2020, November 24). Equality Now. https://equalitynow.org/resource/justicedenied/

[127] Thapa, R., van Teijlingen, E., Regmi, P. R., & Heaslip, V. (2021). Caste Exclusion and Health Discrimination in South Asia: A Systematic Review. Asia-Pacific journal of public health, 33(8), 828–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395211014648

[128] Jaswal, S. (2022, April 27). Is India’s food security scheme discriminating against Dalits? Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/27/is-india-food-security-scheme-discriminating-against-dalits; Dalits in India. (n.d.). Minority Rights Group. https://minorityrights.org/communities/dalits

[129] 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: India. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/india/

[130] Pathi, K., Saaliq, S. & Rising, D. (2024, June 4). Modi claims victory in India’s election but drop in support forces him to rely on coalition partners. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/india-election-results-2024-lok-sabha-modi-bjp-7893efecc83fa8225a611f174e6420ee; Rossow, R. M. (2024, June 4). India’s National Election: Surprise and Stability. Center for Strategic & International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/indias-national-election-surprise-and-stability

[131] Pathi, K., Saaliq, S. & Rising, D. (2024, June 4). Modi claims victory in India’s election but drop in support forces him to rely on coalition partners. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/india-election-results-2024-lok-sabha-modi-bjp-7893efecc83fa8225a611f174e6420ee

[132] Shamim, S. (2024, June 6). India election results: Big wins, losses and surprises. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/6/4/india-election-results-big-wins-losses-and-surprises; Bajpaee, C. (2024, June 6). India’s shock election result is a loss for Modi but a win for democracy. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/06/indias-shock-election-result-loss-modi-win-democracy

[133] Khan, M. (2024, June 5). Modi Wins But Is Shackled. Muslims Get Respite From Hindutva. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2024/06/modi-wins-but-is-shackled-muslims-get-respite-from-hindutva/

[134] Dayal, S. & Rajesh, Y. P. (2024, October 8). India’s BJP set to win Haryana vote in boost for Modi, Congress rejects outcome. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-pm-modis-bjp-trails-vote-count-two-provincial-elections-tv-says-2024-10-08/

[135] UN Human Rights Committee publishes findings on Croatia, Honduras, India, Maldives, Malta, Suriname, and Syria. (2024, July 25). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/07/un-human-rights-committee-publishes-findings-croatia-honduras-india-maldives; Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide. (2024, January 12). Countries at Risk for Mass Killing 2023–24: Early Warning Project Statistical Risk Assessment Results. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://earlywarningproject.ushmm.org/reports/countries-at-risk-for-mass-killing-2023-24-early-warning-project-statistical-risk-assessment-results

[136] Rose, I. (2024, October 1). The Lyric Composers of the Concentration Camps. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2024/10/the-lyric-composers-of-the-concentration-camps

[137] Zaffar, H. & Pandit, D. (2022, December 20). Hindutva Pop Is the New Soundtrack to the Anti-Muslim Movement in India. Time. https://time.com/6242156/hindutva-pop-music-anti-muslim-violence-india/

[138] Hadid, D. (2024, April 18). Hindu nationalist music could be destructive ahead of Indian elections, critics warn. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/04/18/1245654933/hindu-nationalist-music-could-be-destructive-ahead-of-indian-elections-critics-w