Deep-Seated Violence, Natural Resources,

and Foreign Investment Inflame Conflict in the DRC

Introduction

Conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has destroyed the lives of millions of its people through death, displacement, and crimes against humanity. The DRC and its people have been abused and exploited by foreign regimes for over a century, and these widespread human rights abuses have no end in sight. The international community can and must take immediate steps to prevent further violence in the DRC through international law.

Resource Abundance and a Legacy of Strife

The DRC is located in south-central Africa. Image courtesy of The World Factbook is located in the public domain.

Topography, Natural Resources, and Geography

The DRC is located in south-central Africa.Located in south-central Africa, the DRC is home to mountain ranges, equatorial rainforests, and abundant waterways and lakes. The Congo Basin is in center of the DRC and is ringed by multiple mountainous regions and many rivers. Varied habitats of the DRC are home to animal species including hippopotamuses, chimpanzees, lowland gorillas, black and white rhinoceroses, giraffes, lions, cheetahs, and innumerable birds, insects, and reptiles. Several national parks of the DRC are designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[1] The country contains rich natural resources, including rubber, copper, coltan, cobalt, uranium, gold, and diamonds.[2]

Colonial Oppression

In 1884, European nations at the Berlin Conference established rules of imperialist conquest and partitioning of Africa.[3] To settle disputes regarding the Congo Basin, the conference recognized the Free State of the Congo, also called the Congo Free State, the boundaries of which are now the DRC. King Leopold II of Belgium, in his personal capacity, was appointed to oversee the Congo Free State as a mercantile sovereignty.[4]

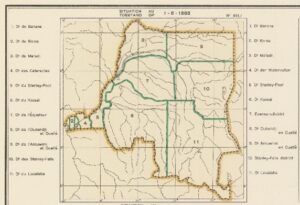

Districts of the Congo Free State, 1950. Image courtesy of Institut Royal Colonial Belge is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

With the Congo Free State as his new personal fiefdom, King Leopold II exploited the region with a brutality remarkable even for an era only recently divested of the slave trade. The invention of vulcanized rubber made the Congo a valuable territory for its vast natural rubber supply. King Leopold II extracted the resource through forced labor by the local population, carried out by appointed white European mercenaries and local militant groups press-ganged into service. Children, especially orphans, were often taken from their homes and sent to work camps or to be trained as soldiers for the occupying forces. Villages were given unattainable quotas of rubber to harvest, and if quotas were unmet, people were punished by mutilation and amputation of hands and feet, torture, rape of the women, and mass killings. Members of revolts were slaughtered en masse by King Leopold’s mercenary force, with the survivors tortured, sent to work camps, or both.[5]

British journalists brought news of the atrocities back to Europe, and the international community called for an end to King Leopold’s mandate over the region. In 1908, amidst the cry of protests, King Leopold II ceded the Congo Free State to the Belgian government, creating the colonial Belgian Congo which lasted until the establishment of the independent DRC in 1960.[6]

Thirty Years of War

Shortly after the DRC gained independence in 1960, 300,000 members of the Tutsi ethnic group fled from Rwanda for the DRC as ethnic tensions rose in their home country. Those tensions simmered until 1994 when extremists of the Hutu ethnic group carried out the Rwandan genocide, killing at least 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in a hundred days. When the current Rwandan President, Paul Kagame, retook the Rwandan capital in July 1994, up to two million extremist Hutu militias, their leaders, and Hutu civilians fearing retaliation fled across the border to the DRC. This influx of emigrants set the stage for the First Congo War in 1996. Remnants of Hutu militias in the DRC regrouped and continued their attacks on Tutsis in the DRC. In response, Rwanda began arming Tutsis inside the DRC to fight the Hutu extremists. DRC militant groups took advantage of the chaos to revolt against the DRC President Mobutu on widespread allegations of corruption. Rwanda supported these rebels, as did Rwanda’s allies. While inside the DRC, the Kagame’s Rwandan troops killed Hutus, attempted to bring Tutsis back to Rwanda, and seized valuable diamond and coltan mining operations in eastern DRC near the Rwandan border. The DRC rebel’s leader Kabila was installed as President, ending the First Congo War.

Less than a year later, Kabila turned on Rwanda, which started the Second Congo War. Kabila armed Hutus in the DRC to fight the Tutsis and Rwandans in the eastern DRC, openly calling for ethnic violence. The Second Congo War ended with treaties in 1999 and the deployment of the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO).[7]

European powers and African neighbors have exploited the DRC economically, held it back politically, and fueled the conflict, which has killed millions and displaced millions more. Mass displacement, ethnic tensions, competition for resources, government corruption, and poverty caused by the DRC’s recent and colonial conflicts have led to constant skirmishing between 120 militant factions for over 30 years.[8]

All prime indicators of impending genocide are present in the DRC today. Today, new powers seek to exploit the natural wealth of the DRC, and old enmities continue to burn. Crimes against humanity and possibly war crimes are occurring in the DRC, and there are accusations of ecocide, the intentional and wanton destruction of the environment, regarding the careless extraction of mineral wealth.

Militia Groups in the DRC

Many perpetrators are involved in the conflict in DRC. In eastern DRC, nearly 120 militia groups are engaged in conflict with each other and civilians. Most of these groups are committing heinous acts of violence against the civilian population.

In February 2024, a militia group called the Cooperative for Development of the Congo (CODECO) attacked a gold-mining village in Ituri province in eastern DRC, killing at least a dozen people and taking 16 more as hostages. CODECO purports to defend the interests of the ethnic Lendu people and is engaged in hostilities against the ethnic Hema people and their self-defense militia called Zaire.[9]

The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) originated in Uganda and has taken up residence in the north-eastern DRC since the First Congo War. The ADF’s original aim was to create an Islamic state in Uganda, and their current goal is unclear. The militia now appears linked to the wider ISIS or ISIL network. The group attacked the village of Mukondi in March 2023.[10]

M23 is currently the most pressing danger in the DRC. M23 is a militant organization that splintered from the Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP) in the Second Congo War. M23 is a group of ethnic Tutsis and purports to defend Tutsi interests in the DRC. M23 is currently approaching Goma, a provincial capital and commercial hub in eastern DRC, north of Lake Kivu and just inside the DRC border with Rwanda. M23 is materially supported by Kagame’s government in Rwanda and has been a deliberate and prolific perpetrator of atrocities in eastern DRC.[11] M23 was formally sanctioned in 2012 by the United Nations Security Council for offenses during armed conflict, such as intentional targeting of women and children, indiscriminate killing and maiming of civilians, kidnapping, forced recruiting of soldiers including children, forced displacement, and sexual violence including at least 46 rapes.[12] Their pattern of abuse against the Congolese people has waxed and waned over the past decade, but as of August 2024, the organization is poised to severely disrupt the already embattled region with its attack on Goma and the surrounding population. The displacement of civilians trying to escape violence on the frontline is worsening an already dire scarcity of food and medicine.

The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), another militia from the First and Second Congo Wars, are an ethnic Hutu Rwandan rebel force loosely allied with the Congolese national army in the fight against M23.[13] The FDLR is led by some Rwandan past genocide leaders, and the group continues to commit brutal acts of violence against Tutsis living in the Congo as well as other groups of civilians and rival militias.[14]

The Congolese national army, or FARDC, is ill-disciplined and ill-equipped for a modern military force, and is under-manned to defend and police the DRC.[15] Due to these shortcomings, the national military is aided by vigilante groups such as the Wazalendo, and in Goma by a force of 1,000 Romanian mercenaries.[16] Government forces are also buoyed for now by MONUSCO peacekeeping forces.

While all these groups are ostensibly engaged in a devastating ethno-political conflict, perhaps the most important driver of violence in the DRC is the land itself and what lies beneath it.

Natural Resources, Greed, and Mining

Natural resources of the Congo are once again the target of international industry, and the pattern of exploitation is repeating. This time, the target is not rubber, but minerals critical to battery and semi-conductor technologies, including the minerals cobalt, coltan, and copper. These materials are crucial to the green energy revolution.

The Congo is rich in natural resources.

Artisanal mining in the Congo. Image courtesy of The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The DRC produces over 70% of the global cobalt supply, and international companies are heavily invested in extracting and processing that mineral wealth.[17] Chinese corporations have extensive mining operations in the region. The mineral processing firms, most of which are also Chinese, source some of their ore from the large-scale mining operations and an unknown quantity of ore from artisanal mining.

Artisanal mining refers to local Congolese practices whereby simple hand tools are used to dig, clean, and sort ore.[18] It is difficult to obtain exact figures on how many individuals are engaged in the practice, or how much their mining efforts yield. There are many reports of child laborers in the mines. Over the past twenty years, child laborers have comprised up to 40% of the artisanal mining workforce.[19] Exposure to large quantities of cobalt is highly toxic: cobalt can cause lung and bladder cancer, reproductive issues and genetic disorders, respiratory illness, and heart disease. Artisanal workers often use no protective equipment and are directly exposed to cobalt through prolonged skin contact and by inhaling cobalt-laden dusts.[20]

Impunity

The DRC’s legal system would be most appropriate to hold the perpetrators accountable for their crimes. However, it is unlikely that domestic courts will be able to enact justice due to the impacts of prolonged war and weak rule of law. As signatories to the Rome Statute, the DRC could seek judicial aid from the International Criminal Court (ICC) to bring specific individuals to justice. Strong cases could be made against leaders of several warring factions for crimes against humanity and war crimes. It is possible that the proposed fifth core international crime of ecocide could be brought against individuals engaged in reckless exploitation of the Congo’s mineral resources. Two of the ICC’s biggest barriers to justice are lack of enforcement mechanisms to bring individuals to the Court, and weak infrastructure to bring victim testimony.

International or Non-International Armed Conflict

Under the Rome Statute, war crimes are held to slightly different standards depending on whether the actors are engaged in international armed conflict or non-international armed conflict. The uniformed national armies of two sovereign states fighting over a border dispute is a clear-cut example of international armed conflict. A civil war between opposition groups within a country is a clear example of non-international armed conflict.

These distinctions become unclear when groups inside a country receive material aid from other countries, as is the case with Congolese conflicts. The simplest solution is to assume the implicated militia groups in the DRC should be held to the standard of actors in a non-international armed conflict. If investigation reveals that the organization received material support from another country, such as M23 receiving aid from Rwanda, then that group is considered to be involved in an international armed conflict.

War Crimes

Article 8 of The Rome Statute creates criminal liability at the International Criminal Court for grave violations of the Geneva Conventions and other internationally unlawful acts, “committed as part of a plan or policy or as part of a large-scale commission of such crimes.”[21]

Unlawful acts for parties involved in non-international armed conflict include certain violations of the Geneva Conventions and customary international law committed against non-combatants. Unlawful acts include murder, mutilation, cruel treatment, torture, committing outrages upon personal dignity including humiliating and degrading treatment, and the taking of hostages.[22]

Under these standards, warring militias of the DRC including its own FARDC military, have committed unlawful acts on civilians.[23] M23 and its leaders are well-documented in perpetrating acts of rape and massacre. All DRC militias take hostages and abduct children to force them into soldiering, which is unlawful under these provisions.

To prove these crimes at the ICC, prosecutors would need to show the contextual element of the crimes (the existence of an armed international or non-international conflict) as well as the mental element, the mens rea, which is more difficult to prove. Proving the mental element has two prongs – a perpetrator must be found to have knowledge of the specific acts and knowledge of the act being contextual to the conflict.

Crimes Against Humanity

Article 7 of the Rome Statute creates criminal liability at the ICC for crimes against humanity. Crimes against humanity include similar crimes to war crimes, but they do not have to occur during armed conflict. A crime against humanity can only occur if it has been committed as part of a widespread and systemic campaign against civilians in pursuit of the goals of a State or organization.

Organizations like M23, the ADL, and CODECO could be charged under Articles 7 or 8 of the Rome Statute. Crimes against humanity charges could also be brought against corporate leaders that exploit civilians through mining efforts, particularly Chinese corporations and government officials who oversee resource extraction in the DRC. The charge most applicable is Article 7(1)(k), “Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.”[24] This charge would apply due to willingness of corporate interests, especially Chinese corporations, to encourage use of artisanal mining practices. This practice is physically crippling, highly toxic, and often uses child labor. These corporate interests knowingly prioritize profit at the expense of the civilian population.

Deforestation in the Congo Basin. Image courtesy of GRID-Arendal is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Ecocide

The effort to codify ecocide in the Rome Statute is gaining momentum.[25] Ecocide recognizes that humanity requires the natural world and depends on it, and destruction of the environment is akin to destruction of humanity. The word ecocide means ‘to destroy one’s home.’ The crime has a specific intent element – that is, the actor engaged in rampant or reckless destruction of the natural environment must have the intent to destroy it. Intent can be difficult to prove. The process of mining and logging are inherently destructive to the environment in the Congo, and companies accused of ecocide could claim that they take precautions, do not intend to destroy the environment, and the destruction is merely a byproduct of their operations.

Successful Prosecutions

Despite difficulty prosecuting crimes in the DRC, there have been successful cases at the ICC. The first ever ICC investigation was the Situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which led to convictions of Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, Germain Katanga, and Bosco Ntaganda.[26] Three other cases brought forward did not lead to convictions:

- Charges were considered against Callixte Mbarushimana but went unconfirmed.

- Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui was acquitted of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

- An arrest warrant was issued for Sylvestre Mudacumura, who remains at large.[27]

The ICC will not conduct a trial in absentia, and the warrant against Mudacumura has been outstanding for over a decade, highlighting a difficulty for the ICC in bringing justice.

A Strong Precedent Set by The Lubanga Case

Former child soldiers in the Congo. Image courtesy of L. Rose, USAID, is located in the public domain.

The Lubanga conviction set a strong precedent. Lubanga was convicted of “forcibly conscripting or enlisting” children under the age of 15 to participate in active hostilities.[28] The defense asserted the children consented to being recruited and therefore Lubanga could not have been guilty of forcibly “conscripting or enlisting” them. The Court referred to the standard of customary international law prohibiting use of children in armed conflict, whether forcibly conscripted or otherwise recruited, and dismissed the consent defense. The Court thereby took “conscripting” to mean “forcibly recruiting” and “enlisting” to mean “recruiting volunteers.”[29]

The ICC’s ability to create precedent in this way, through an integration of customary international law and application of the Rome Statute, may be an important factor in bringing other DRC actors to justice at the international level. Specifically, the Court’s willingness to apply customary international law to an imperfectly formulated cause of action may aid in future ecocide prosecutions against foreign interests in the DRC.

Attaining Peace

Peace has eluded the Congo for hundreds of years. Brief spells of truce and ceasefire are habitually broken by domestic and foreign actors seeking to advance their own interests. While no domestic or international policy will remove Congo’s violent past or the effects on Congolese society today, there are paths available that can provide some measure of justice and stability.

Important Considerations

At the Berlin Conference which began the Congo’s 100+ years of conflict, consideration was not given to Congo’s sovereignty. International responsibilities and rights to the Congolese people were referenced only as a pretext for economic exploitation.

Discussions of international aid or solutions to the present conflicts in the DRC cannot make the same mistake. If we wish to apply Westphalian ideals of sovereignty, international cooperation, respect, and self-determination to the situation in the Congo, then we must do so, even at the expense of Western interests in the Congo. Western nations currently prop up the failing Congolese government while simultaneously undermining it with exploitative industrial practices. This hypocrisy functions to hinder Congolese development and international legitimacy. In order to beneficially support the DRC’s development, we must also challenge China’s investment and influence in the country.

An End to Active Hostility

The first step to any lasting solution is an immediate end to active hostilities in the DRC. Negative peace, or the absence of violence, is essential to allow the DRC to develop policies which can engender lasting positive peace.

MONUSCO supports FARDC forces in peacekeeping operations in the Beni region of eastern Congo, 2014. Image courtesy of UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Over the past thirty years, ceasefire attempts have been unsuccessful. Intervention of UN MONUSCO peacekeepers helped bring an end to the Second Congo War, but Congolese attitudes towards UN troops have soured and MONUSCO is leaving the country, handing over bases to the FARDC forces.[30]

Many organizations and countries have a strong interest in DRC stability and security, including the African Union, the South African Development Community, the East African Community, and the United Nations. All these organizations can provide a venue for peace talks. Rwanda must accept accountability for supporting M23 and either work to bring the group back within the bounds of lawful conduct or bring members to justice. That commitment must be met with a measure of forgiveness on the part of the DRC and a promise of no further retaliation for Rwanda’s wrongs. The cycle of violence will continue if neither country is willing to accept accountability. Retributive justice should be avoided as it will fuel animosity and tensions which will reignite later violence.

If the DRC government is open to assistance, a new peacekeeping campaign with broad UN support may be effective in bringing peace. The outgoing troop count was too low to effectively police the country. A professional soldier presence across the country could establish rule of law to stop militia violence against civilians and allow the government to repair damaged infrastructure, establish beneficial relationships with the foreign interests, and offer victims services and justice.

Building Positive Peace

Rebuilding trust in the government and justice system of the DRC is essential to building positive peace where the people of the Congo can utilize rule of law to settle conflict.

The DRC currently only allows military tribunals to hear cases regarding Rome Statute crimes. This provides difficulty to hold DRC officials complicit in crimes against civilians. Victims must have access to justice through the domestic court system.[31] This includes allowing victims to testify directly and appointing a neutral or non-military prosecutor to investigate and charge cases. It may also be appropriate for the UN Security Council to establish an ad hoc tribunal within the DRC. While it is unlikely China would approve of a tribunal due to their perpetration of human rights abuses in the DRC, significant international pressure should be applied on this issue.

Conclusion

The Congolese people have suffered from economic exploitation, ethnic persecution, and endemic violence for over a century. The international community has historically caused conflict in the Congo, has failed to remedy those wrongdoings, and must take action to uphold international law. If the DRC expresses a desire for international intervention, the United Nations, the United States, and the European Union must act to provide the DRC with resources to reform its government. There should be no consideration of cost or of repayment. If, as an international society, we truly believe in sovereignty, human dignity, and self-determination, then we must make all possible efforts to provide the Congolese people with tools for security and justice.

This page was written by By Nolan Woods, Mitchell Hamline School of Law, spring 2024.

References

[1] Democratic Republic of the Congo. Dennis D. Cordell, René Lemarchand, Bernd Michael Weise, Encyclopedia Britannica, April 25, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/place/Democratic-Republic-of-the-Congo

[2] DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth, BBC News, October 9, 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24396390

[3] Patrick Gathara, Berlin 1884: Remembering the conference that divided Africa, Al Jazeera, November 15, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/11/15/berlin-1884-remembering-the-conference-that-divided-africa

[4] The Conference at Berlin on the West-African Question, De Leon, supra.

[5] Leopold II: Belgium ‘wakes up’ to its bloody colonial past, Georgina Rannard, Eve Webster, BBC News, June 12, 2020. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53017188. See also A Forgotten Genocide: The Congo Free State, Paul Gregoire, Sydney Criminal Lawyers, July 26, 2017. Available at: https://www.sydneycriminallawyers.com.au/blog/a-forgotten-genocide-the-congo-free-state/

[6] Leopold II: Belgium ‘wakes up’ to its bloody colonial past, Georgina Rannard, Eve Webster, BBC News, June 12, 2020. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53017188. See also A Forgotten Genocide: The Congo Free State, Paul Gregoire, Sydney Criminal Lawyers, July 26, 2017. Available at: https://www.sydneycriminallawyers.com.au/blog/a-forgotten-genocide-the-congo-free-state/

[7] A guide to the decades-long conflict in DR Congo, Shola Lawal, Al Jazeera, February 21, 2024. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/21/a-guide-to-the-decades-long-conflict-in-dr-congo

[8] A guide to the decades-long conflict in DR Congo, Shola Lawal, Al Jazeera, February 21, 2024. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/21/a-guide-to-the-decades-long-conflict-in-dr-congo

[9] Rebels attack a gold mine in eastern Congo, killing at least 12 people, Jean-Yves Kamale, Associated Press, February 15, 2024. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/congo-killings-militia-codeco-mine-lendu-hema-51483cdad8c4d916d2f73263445cdc28

[10] A guide to the decades-long conflict in DR Congo, Shola Lawal, Al Jazeera, supra.

[11] Escalating Violence in Democratic Republic of Congo Exacerbating Humanitarian Crisis, Special Representative Warns Security Council, Urging Durable Political Solution, United Nations Meeting Coverage and Press Releases, 9553RD MEETING (PM), SC/15596, February 20, 2024. Available at: https://press.un.org/en/2024/sc15596.doc.htm

[12] M23, United Nations Security Council, Narrative Summary available at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/1533/materials/summaries/entity/m23

[13] DR Congo: Army Units Aided Abusive Armed Groups, Human Rights Watch, October 18, 2022. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/18/dr-congo-army-units-aided-abusive-armed-groups

[14] DR Congo: Army Units Aided Abusive Armed Groups, Human Rights Watch, October 18, 2022. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/18/dr-congo-army-units-aided-abusive-armed-groups

[15] The Overlooked Crisis in Congo: ‘We Live in War’, Declan Walsh, The New York Times, December 17, 2023. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/17/world/africa/democratic-republic-of-congo-elections.html

[16] The Overlooked Crisis in Congo: ‘We Live in War’, Declan Walsh, The New York Times, December 17, 2023. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/17/world/africa/democratic-republic-of-congo-elections.html

[17] Ranked: The World’s Top Cobalt Production Countries, Bruno Venditti, Visual Capitalist, July 24, 2023. Available at: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ranked-the-worlds-top-cobalt-producing-countries/.

[18] China, the democratic republic of the congo, and artisanal cobalt mining from 2000 through 2020, Andrew L. Gulley, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Jun. 2023). Available at: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2212037120#fig02

[19] China, the democratic republic of the congo, and artisanal cobalt mining from 2000 through 2020, Andrew L. Gulley, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Jun. 2023). Available at: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2212037120#fig02

[20] Sustainability of artisanal mining of cobalt in DR Congo, Banza Lubaba Nkulu C, Casas L, Haufroid V, De Putter T, Saenen ND, Kayembe-Kitenge T, Musa Obadia P, Kyanika Wa Mukoma D, Lunda Ilunga JM, Nawrot TS, Luboya Numbi O, Smolders E, Nemery B., PubMed (2018), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6166862/ (explaining the results of a case study of the city Kolwezi in the Katanga Copperbelt, a DRC mining hub.)

[21] Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (last amended 2010), ISBN No. 92-9227-227-6, UN General Assembly, July 17, 1998. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/legal/constinstr/unga/1998/en/64553 [accessed 29 April 2024]

[22] Rome Statute, Article 8, Section 2(c)(i-iii).

[23] DR Congo: Army Units Aided Abusive Armed Groups, Human Rights Watch, October 18, 2022. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/18/dr-congo-army-units-aided-abusive-armed-groups

[24] Art. 7(1)(k) Crime against humanity of other inhumane acts, Case Matrix Network, available at: http://www.casematrixnetwork.org/cmn-knowledge-hub/proof-digest/art-7/7-1-k

[25] ECOCIDE: A NEW CHALLENGE FOR THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW AND FOR HUMANITY, Camila Misko Moribe, Flávio de Leão Bastos Pereira, Nathalia Penha Cardoso de França, JICL, Volume 4 Issue 1, 28-40.

[26] Democratic Republic of the Congo, ICC-01/04, The International Criminal Court, available at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/drc

[27] Democratic Republic of the Congo, ICC-01/04, The International Criminal Court, available at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/drc

[28] Judgment pursuant to Article 74 of the Statute, THE PROSECUTOR v .THOMAS LUBANGA DYILO, No. ICC-01/04-01/06-2842, March 14, 2012. Available at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/court-record/icc-01/04-01/06-2842

[29] Judgment pursuant to Article 74 of the Statute, THE PROSECUTOR v .THOMAS LUBANGA DYILO, No. ICC-01/04-01/06-2842, March 14, 2012. Available at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/court-record/icc-01/04-01/06-2842

[30] UN peacekeepers close base in preparation to leave DR Congo, Al Jazeera, April 26, 2024. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/26/un-peacekeepers-close-base-in-preparation-to-leave-dr-congo

[31] Prosecuting international crimes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Using victim participation as a tool to enhance the rule of law and to tackle impunity, Pacifique Muhindo Magadju, Derek Inman, African Human Rights Law Journal 293-318 (2018). Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2018/v18n1a14