Spain: Universal Jurisdiction Prosecution for Genocide in Tibet

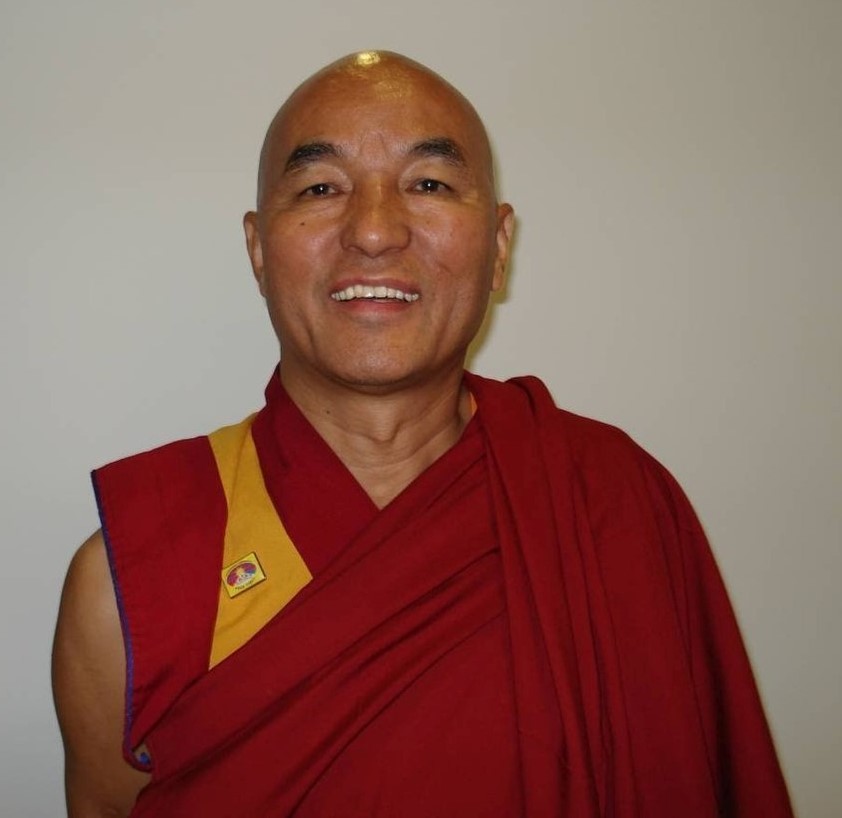

Thubten Wangchen, 2008. Image courtesy of RODIXETA is cropped and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

In June 2005, Thubten Wangchen Sherpa, a Tibetan victim-survivor of genocide in Tibet and a Spanish national, filed a complaint with Spain’s national court, accusing former Chinese government and military officials of committing acts of genocide and torture in Tibet.[1] This legal action was supported by Madrid- based human rights organizations marking a crucial effort to hold Chinese officials accountable.[2]

The complaint used the principle of universal jurisdiction, which enables national courts almost anywhere to prosecute individuals for human rights atrocities including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, regardless of where the crime was committed and the nationality of the perpetrators or victims.[3] This principle aims to ensure that perpetrators of such atrocities do not escape justice by fleeing to another jurisdiction that does not recognize international criminal law.

Spain was considered a pioneer in its application.[4] This framework enabled Spanish courts to pursue cases involving international crimes committed abroad, providing an avenue for victims when national courts had been or are unwilling to act.[5] In 1998, Judge Garzon issued an international arrest warrant for former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, who was accused of human rights abuses, including the torture and forced disappearances, during his rule from 1973 to 1990.[6] The case was initiated by complaints from Spanish citizens of Chilean origin. Pinochet’s arrest marked the first time a former head of state was detained under the principle of universal jurisdiction. While Pinochet was never tried in Spain, the case set a precedent for the use of universal jurisdiction, showing an increasing willingness to hold former leaders accountable for human rights atrocities.

However, the application of universal jurisdiction in Spain has faced significant challenges, especially when it involved powerful foreign nationals or sensitive geopolitical issues. The case brought by Thubten Wangchen Sherpa illustrates these challenges.

The complaint targeted high-ranking Chinese officials, including former President Jiang Zemin and former Premier Li Peng, and accused these officials of orchestrating systematic repression, including mass killings, torture, and the destruction of Tibetan culture and religion.

National Court of Spain, Audiencia Nacional, in Madrid. Image courtesy of FDV is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Spain’s national court admitted the case, recognizing the severity of the allegations and the relevance of universal jurisdiction. In 2013, the Spanish National Court issued international arrest warrants for Jiang Zemin, Li Peng, and other Chinese officials. These warrants set an international precedent for legal action against high-ranking officials accused of human rights abuses.[7]

The case garnered substantial attention and prompted swift and strong negative reactions from the Chinese government, which condemned the proceedings as a violation of its sovereignty.[8] The diplomatic pressure on Spain was intense and China sought to have the case dismissed.

In 2014, in response to the diplomatic tensions and economic considerations, the Spanish government enacted significant limitations to its universal jurisdiction laws. These changes drastically circumscribed the scope of universal jurisdiction in Spain, imposing stricter conditions for cases to be heard.[9] The amendments required that the accused be present on Spanish soil or that the victims be Spanish nationals or residents at the time the crimes were committed.[10] This legal reform narrowed the applicability of universal jurisdiction and constrained the ability of Spanish courts to pursue cases involving foreign nationals and international crimes.

Spain’s diplomatic and economic relationship with China directly influenced these legal changes. In the case of Thubten Wangchen Sherpa, Spanish courts had initiated investigations against Chinese officials for alleged human rights abuses. China’s reaction included threats of economic retaliation. The Chinese government hinted at reducing investments and imposing trade barriers against Spain. These threats underscored the importance of maintaining favorable diplomatic relations. Additionally, there was a broader concern that ongoing legal actions against officials from various countries might make Spain less attractive to foreign investors. Multinational corporations and foreign governments could perceive Spain as a risky environment due to the potential for legal actions against nationals, deterring investment and economic partnerships.[11]

Ultimately, the 2014 reforms to Spain’s universal jurisdiction laws were influenced by the need to balance justice and international accountability with practical considerations. By requiring a closer connection to Spain for cases to proceed Spain demonstrated the choice of a pragmatic approach over one that emphasized human rights.

As a result, the National Court dismissed the case. The new legal constraints made it impossible to proceed with the case. The outcome underscored the influence of political and economic pressure on judicial proceedings, what is often termed ‘lawfare.’

The financial relationship between China and Spain played a critical role in influencing legal reforms. Up until 2008, Spain received limited Chinese investment. However, following the Eurozone crisis in 2009, China’s economic influence in Spain expanded considerably. China became Spain’s second largest international creditor by purchasing substantial amounts of Spanish debt. This increased economic interdependence facilitated the strengthening of Spain’s economic and political ties with China throughout the administration of Mariano Rajoy (2011-2018). This period was marked by a discreet handling of sensitive issues, including the complaint brought by Thubten Wangchen Sherpa, which triggered arrest warrants for former high-ranking Chinese officials involved in the Tibetan genocide. This context underscores how economic considerations influenced diplomatic relations, contributing to a nuanced approach in managing international relations with China.[12]

In September 2014, following the arrest warrants (actual arrests were never made), Rajoy made a visit to China that resulted in trade agreements worth €3.2 billion. Evidently, since the 2008 economic crisis, China and Spain have developed a robust trade relationship, with China becoming one of Spain’s largest trading partners. This economic interdependence includes significant Chinese investment in Spain’s energy, infrastructure, real estate, tourism, and technology sectors. Such investments are significant given that as of December 31, 2015, China is the tenth largest investor in Spain, with a 2.65 percent share of Spain’s stock of inward foreign direct investment.[13]

China now holds major financial interests in the Port of Valencia, which is a main commercial gateway to the Iberian Peninsula. Image courtesy of Codex is unmodified and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) served to strengthen these ties by involving Spanish companies in various infrastructure projects and increasing Chinese investment in Spanish ports and railways. In addition, participation in the BRI has spurred economic growth and created job opportunities within Spain. As of 2020, Chinese tourism in Spain was steadily increasing, with an estimated 200,000 Chinese immigrants already in the country, often for academic and research purposes.[14] It is important to note that academic endeavors are not the only motivations for immigrating to Spain. Many Chinese immigrants in Spain are entrepreneurs in the trade, retail, and hospitality sectors. Others are employed in an array of sectors including manufacturing, construction, education, healthcare, and IT.

Now, while the BRI has provided a vast array of economic benefits, in terms of job opportunities, travel and tourism and the expansion of various sectors (education, healthcare, manufacturing to name a few) it has also influenced Spain’s diplomatic relations. Spain must now take a balanced approach when it comes to sanctions against China, otherwise there could be a significant loss of investment. China’s investment in Spain, through the BRI, has created a climate where Spain must balance its economic interests with its political interests, an endeavor that has adversely impacted the application of the principle of universal jurisdiction.

This page was authored by Brieanna Da Silva, Research Associate; updated August 2024.

References

[1] Craig Peters, The Impasse of Tibetan Justice: Spain’s Exercise of Universal Jurisdiction in Prosecuting Chinese Genocide, Seattle University Law Review, Vol. 39:165, p. 166.

[2] Comité de Apoyo al Tibet (CAT)

[3] Beth Van Schaack & Ronald C. Slye, International Criminal Law and Its Enforcement: Cases and Materials 99 (2nd ed. 2010).

[4] Inmaculada Sanz, China Bristling, Spain Seeks to Curb its Judges’ International Rights Clout, Reuters, February 11, 2014. See https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSBREA1A1KC/.

[5] Id. at 3.

[6] Reuters, Spain High Court Dismisses China Rights Cases, June 23, 2014. See https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN0EY2IT/.

[7] Id. at 3.

[8] Id. at 3.

[9] Andres Ortega, Spain, and Chain: A European Approach to an Asymmetric Relationship, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 15, 2019. See https://www.csis.org/analysis/spain-and-china-european-approach-asymmetric-relationship.

[10] Id. At 7.

[11] Craig Peters, The Impasse of Tibetan Justice: Spain’s Exercise of Universal Jurisdiction in Prosecuting Chinese Genocide, Seattle University Law Review, Vol. 39:165, p. 166.

[12] Mario Esteban, A Look at the Future of Relations between Spain and China, Real Instituto Elcano, April 4, 2023. See https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/a-look-at-the-future-of-relations-between-spain-and-china/.

[13] Id. At 9.

[14] Id. At 7.