Democratic Republic of the Congo

What

Since 1996, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC; Congo) has been embroiled in violence that has killed as many as 6 million people. The conflict has been the world’s bloodiest since World War II. The First and Second Congo Wars, which sparked the violence, involved multiple foreign armies, ad hoc militia groups, and investors from Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, Chad, Libya, and Sudan, among others, and has been so devastating that it is sometimes called the “African World War.”

Fighting continues in the eastern parts of the country, destroying infrastructure, causing physical and psychological damage to civilians, and creating human rights violations on a massive scale. Rape is being used as a weapon of war, and large-scale plunder and murder are also occurring in efforts to displace people from resource-rich land.

Today, most of the fighting is taking place in the regions of North and South Kivu, on the DRC/Rwanda border. Some fighting is political, resulting from unrest caused by Hutu refugees from the 1994 Rwandan genocide now living in DRC, while other fighting results from an international demand for natural resources. DRC has large quantities of gold, copper, diamonds, and coltan (a mineral widely used in cell phones and other small electronics), which many parties desire to control for monetary reasons. However, funds from the sales of these resources has not reached average citizens. Currently the education, healthcare, legal, and road systems are in shambles.[1]

Where

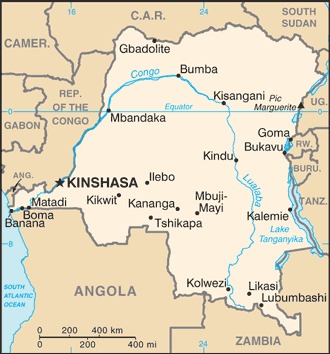

The DRC, formerly known as Zaire, is located in Central Africa. To the north, it is bordered by the Central African Republic and Sudan; to the east, by Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania; and to the south by Zambia and Angola. The capital city, Kinshasa, is located in the far western area of the country. DRC covers about 905,000 square miles and has a population of almost 96 million people, with one of the highest population growth rates in the world.[2]

Although citizens of the DRC are among the poorest in the world, having the fifth lowest GDP per capita globally, the country is widely considered to be the richest country in the world regarding natural resources below the ground, with untapped deposits of raw minerals estimated to be worth in excess of US $24 trillion.[3]

When

The violence in DRC is closely related to the genocide that occurred in Rwanda in 1994. In this genocide, groups of hard-line militant Hutus, known as the Interahamwe, slaughtered ethnic Tutsis and politically moderate Hutus. The RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front), a Tutsi-led militia, defeated the Hutu movement and came to power in July 1994. Immediately following the RPF takeover, nearly 2 million Hutus fled into neighboring countries to avoid potential Tutsi retribution.[4]

The Hutus’ refugee camps on the Rwanda-Zaire (DRC) border became army bases, of sorts, and gave extremists easy access to invade and execute terror attacks in Rwanda for two years. In 1996, joint Uganda-Rwandan armies led by Laurent Kabila invaded eastern Congo, thus starting the First Congo War. It ended in May of 1997 when dictator-president Sese Seko Mobutu was overthrown by Kabila’s army.[5]

MONUSCO Forces destroying a camp previously occupied by the FDLR. Image by Monusco/Force | Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) | License

The Second Congo War, or African World War, began in 1998. Kabila distanced himself from his original alliance with Rwanda and Uganda and, a week later, Rwanda invaded eastern Congo for various reasons.[6] Neighboring African countries then intervened on both sides.[7] Ultimately, the war became a stalemate and was officially declared over in 2003.[8]

However, Congo’s instability remained even after the 2003 peace agreements. Specifically, a proxy war between Rwanda and Congo continued in the east until the end of 2008. Here, Congolese Tutsi warlord General Laurent Nkunda waged a campaign to destroy Hutu rebels from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR).[9] The FDLR, a Hutu-led group stemming from the 1994 genocide, was bent on destroying Tutsi influence and uses violent, terror-based means like those used during the genocide to do so. Nkudna accused the Congolese government of backing the FDLR.[10] A change in the conflict came about in late 2008 when Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo joined forces to combat the FDLR in North and South Kivu provinces.[11] But the bitter conflict has continued unabated, and Congolese government troops, backed by thousands of U.N. peacekeepers, have failed to defeat the FDLR rebels.[12]

Tensions are still high on the Rwandan border, where Rwanda’s Tutsis continue to feel threatened by Hutu rebels. Since the majority of the forces in the DRC’s conflict were non-governmental militias, disarming or controlling them since the ceasefires were signed has proven difficult. Conflict continues over the plentiful natural resources in the DRC. Violence is especially prevalent in the East, which is rich in minerals, diamonds, and timber.[13]

The Lord’s Resistance Army has expanded its operations from northern Uganda into the DRC. The LRA is notorious for kidnapping children, forcing them to kill and maim innocent victims, and using young girls as sex slaves. Attacks by the LRA spread fear and the threat of famine through northeast DRC as the LRA extended its abduction and terror raids across the region. [14] New conflicts between the LRA and FARDC have left thousands of civilians dead. The LRA is documented as still active in its abductions in 2019. [15]

In 2016, violence erupted in the southeastern region of Kasai after a tribal chieftain was killed for rebelling against President Joseph Kabila, son of Laurent Kabila who had originally led the Congo invasion in the First Congo War. Violence escalated into 2017, killing over 3,000 people in the region. Between March and June, 250 people died in targeted killings led by government forces and militias using child soldiers. The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that 1.4 million in the Kasai region have fled their homes.[16]

In 2022, despite the official normalization of diplomatic relations, tensions mounted between DRC and Rwanda. The M23 rebel group, reemerged after five years of inactivity and began escalating attacks against Congolese troops. The group seized significant territory along the Rwandan and Ugandan borders. Kinshasa accused Rwanda of funding and supporting M23’s resurgence (a claim supported by the African Union and the United States). In response, Rwanda accused Kinshasa of once again aiding extremist Hutu extremist militias and increased its military presence inside the Congo. Rwanda and DRC have been on a war footing since the end of 2022.[17]

Rwanda and Uganda—and militias with their support—have financial stakes in Congolese mines (though they are not always legitimate), adding more fuel to the fire. Additionally, China is involved in both the internal conflict and the economic landscape of the DRC. The Congolese government is employing Chinese drones and weaponry in its battle against the M23 rebels. Uganda has also purchased Chinese arms to carry out military operations within DRC’s borders. China’s negotiations with Congolese leadership, especially during the Joseph Kabila regime, have granted Chinese firms unprecedented access to metals crucial for the mass production of electronics and clean energy technologies. The Beijing-Kinshasa relationship came under international scrutiny leading up to President Kabila’s resignation in 2019 when evidence revealed that Chinese capital—intended for infrastructure investment as repayment for mining rights—was being funneled to Joseph Kabila and his associates. China and DRC’s complex, multi-layered economic and military relationship has resulted in limited access to the Congo’s vital resources and profits for other countries and the Congolese people themselves.

Russia also maintains a relationship with the DRC. Following its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Moscow has been courting support from several African nations, including the Congo. While DRC voted in favor of a February 2023 resolution to condemn the war and demand Russia’s withdrawal from Ukraine, other African countries with stronger ties to Moscow abstained or voted in opposition.[18]

How

Several million people have died in Congo from conflict that began in 1996. The death toll is due to widespread disease and famine; reports indicate that almost half of the individuals who have died are children under the age of 5.[19]

The long and brutal conflict in the DRC has caused massive suffering for civilians, with estimates of millions dead either directly or indirectly as a result of the fighting. There have been frequent reports of weapon bearers killing civilians and destroying property.

Those who are not subject to violence must contend with poverty, famine, and disease. Hundreds of thousands of people have been impoverished by the violence. Infant and child mortality rates are extremely high as a result of famine and malnutrition. An estimated 4.5 million people have been displaced within the DRC and 3 million Congolese have become refugees in neighboring Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda.[20] [21]

The prevalence of rape and other forms of sexual violence is considered the worst in the world. In May 2011, the New York Times reported that a woman is raped every minute in the Congo. Aside from the severe physical and psychological trauma experienced by rape victims, sexual violence has contributed to the spread of sexually–transmitted diseases, especially HIV/AIDS.[22]

In 2003, Sinafasi Makelo, a representative of Mbuti pygmies, told the UN’s Indigenous People’s Forum that, during the war, his people were hunted down and eaten as though they were game animals. In neighboring North Kivu province, there has been cannibalism by a group known as Les Effaceurs (“the erasers”), who wanted to clear the land of people to open it up for mineral exploitation. Both sides of the war regarded the Mbuti as “subhuman” and expendable.[23]

As of 2023, DRC is home to an estimated 5.7 million internally displaced people in urgent need of more than 2 billion dollars in medical and other aid. Nearly one million Congolese nationals have sought refuge in various African states. Exacerbating this need for assistance, the UN has had to suspend air deliveries of aid to certain eastern provinces in the face of attacks on its convoys.[24]

MONUSCO. Image by Monusco/Penangnini Toure| Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)| License

Response

The UN’s first mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo, called MONUC, began in 1999. MONUC was renamed MONUSCO in July 2010 to demonstrate a new phase in the country. It is mandated to protect civilians and also help in the reconstruction of the country. In 2013, Forced Intervention Brigade was created as a part of MONUSCO to actively neutralize armed groups within the DRC.[25] As of March 2020, MONUSCO is made up of 18,316 uniformed personnel; however, despite this presence, rebels continue to kill and plunder natural resources with impunity.[26] Some claim the rebels are supported by an international crime network stretching through Africa to Western Europe and North America.[27]

The international community’s support for political and diplomatic efforts to end the war has been relatively consistent, but few steps have been taken to abide by repeated pledges to demand accountability for the war crimes and crimes against humanity that are routinely committed in Congo. United Nations Security Council and the U.N. Secretary-General have frequently denounced human rights abuses and the humanitarian disaster that the war unleashed on the local population. But they have shown little will to tackle the responsibility of occupying powers for the atrocities taking place in areas under their control, areas where the worst violence in the country took place.[28]

On March 14, 2012, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued a ‘guilty’ verdict against Thomas Lubanga Dyilo on charges of rape, murder, and the use of child soldiers, the first verdict for the ICC. In 2014 and 2019 respectively, Germain Katanga and Bosco Ntaganda were also given guilty verdicts. In total, there have been 6 cases tried, with one currently ongoing as of 2020, and one suspect still at large.[29]

In December of 2016, President Joseph Kabila’s second term ended, thus officially ending his constitutionally– mandated term limit. However, despite interventions by various parties, including the Catholic Church and UN ambassadors, Kabila was able to delay the election until December of 2018.[30] The election was then held with irregularities, suppression, and over a million Congolese, in particularly pro-opposition areas, unable to vote in the elections. Despite these tactics, in January of 2019 Felix Tshisekedi was sworn in as president.[31]

Following a UN inquiry showing links between the Rwandan government and the M23 rebel group, an increasing number of human rights organizations and foreign governments, including the European Union and the United States, called on Rwanda to stop supporting the M23 in late 2022. The growing diplomatic pressure on Rwanda could lead to a withdrawal of support and diminish the strength of M23 forces.[32]

Future

Looking forward, the likelihood for improvements in the DRC’s human rights situation remains unknown. Under Joseph Kabila, human rights abuses carried on through opposition and press suppression. Armed conflict also raged on through 2018 in Eastern Congo, displacing and terrorizing thousands of citizens.[33]

Under Tshisekedi’s reign so far, political repression has declined, and many detained political prisoners have been freed.[34] However, senior officers who have committed human rights abuses remain in power in Tshisekedi’s government, and in September of 2019 Tshisekedi declared that he had “no time to rummage into the past” and hold suspected perpetrators of human rights violations and abuses accountable.[35] In addition, armed conflicts led by various rebel and militia groups continue to affect innocent civilians.[36]

In March 2023, M23 agreed to a cease-fire with the Congolese government. Shortly after M23 violated this agreement and declared another one in April 2023. Nonetheless, this fragile truce has done little to alleviate violence, which continues to come in waves. The number of causalities is increasing as armed groups attack displacement camps, civilians in the DRC and abroad, and self-defense groups.[37]

Presidential and parliamentary elections are expected to be held in the Democratic Republic of Congo on December 20, 2023.[38] In May 2023, the South African Development Community (SADC) agreed to deploy troops to eastern Congo to assist UN forces ahead of the elections.[39] However, a month later the UN announced a planned withdrawal from the MOUSCO peacekeeping mission, a decision the United States called premature.[40] UN officials have acknowledged this withdrawal poses the risk of a security vacuum amongst a deteriorating security situation in Ituri and North Kivu.[41]

Written by Zofsha Merchant; updated by Joanna Michalopoulos, October 2023.

References

[1] http://www.responsibilitytoprotect.org/index.php/crises/crisis-in-drc

[2] https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/dr-congo-population/

[3] https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/economy

[4] https://worldwithoutgenocide.org/genocides-and-conflicts/rwandan-genocide

[5] https://enoughproject.org/blog/congo-first-and-second-wars-1996-2003

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://www.thoughtco.com/second-congo-war-43698

[8] http://www.easterncongo.org/about-drc/history-of-the-conflict

[9] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-11108589

[10] https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/para/fdlr.htm

[11] BBC, op. cit.

[12] BBC, op. cit.

[13] http://www.responsibilitytoprotect.org/index.php/crises/crisis-in-drc

[14] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/aug/31/uganda-rebels-lra-terrorise-congo

[15] [https://invisiblechildren.com/blog/2019/05/02/crisis-tracker-alert-abductions-drc/

[16] [https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/2017/11/kasai

[17] https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo

[18] Ibid.

[19] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2223004/

[21] https://www.resettlement.eu/resource/refugees-democratic-republic-congo

[22] https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/12/world/africa/12congo.html

[24] https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo

[25] https://www.lawfareblog.com/militarizing-peace-un-intervention-against-congos-terrorist-rebels

[26] https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/monusco

[27] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-11108589

[28] https://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/drc2/DRC0802-05.htm

[29] https://www.icc-cpi.int/drc

[30] https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/democratic-republic-congo

[31] https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/democratic-republic-congo

[32] https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/02/06/dr-congo-atrocities-rwanda-backed-m23-rebels

[33] HRW 2019, op. cit.

[34] HRW 2020, op. cit.

[36] HRW 2020, op. cit.

[37] https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo

[38] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/congo-schedules-presidential-elections-dec-2023-2022-11-26/

[39] https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo

[40] Ibid.