Transnational Repression:

A Threat to Individuals Worldwide

Introduction

“China wants to make us disappear, and make us afraid, and make us obey.”[1] These are the harrowing words of Gulbahir Haitiwaji, a Uyghur woman subjected to transnational repression perpetrated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). She is a petroleum engineer who immigrated to France with her family and was living a prosperous life. One day in 2016, she received a strange phone call from her employer, asking her to return to China to sign some pension papers. Obliging her employer, she returned to China for what she thought was a few weeks. Instead, she was arrested by Chinese authorities and detained in camps with other Uyghur women. She was relentlessly interrogated about a picture the CCP had obtained of her daughter in France at a protest on behalf of Uyghurs.

In the detention camp, she was unable to close her eyes during the day, even when exhaustion took over, for worry of being accused of praying. If caught, guards would violently drag her from her cell. She and the other detainees were forced to sleep on hay mattresses while under constant video surveillance. She was forced to memorize and sing Chinese propaganda songs. A year later, she was put on trial without a lawyer. The judge sentenced her to seven years of “re-education.” All of this was occurring while her husband and two children were waiting for her in France with no knowledge of her arrest or internment.

In return for her release, Ms. Hatiwaji gave a coerced confession in which she denounced Uyghur activism. She called her family in France and told them to stop all Uyghur activism if they wanted her released. A CCP officer listened closely, recording the entire conversation. A judge then declared her innocent, and she flew back to France in 2019.

Ms. Haitwaji’s story is just one in an increasing epidemic of transnational repression.

What is Transnational Repression?

Transnational Repression (TNR) describes a repressive government’s behavior to silence their citizens living abroad.[2] These citizens may be exiles, dissidents, human rights activists, or political opponents. TNR can also include foreign governments targeting U.S. citizens with family in foreign countries. TNR actions include stalking, harassment, assassination, abduction, digital threats, freezing of financial assets, and family intimidation.[3] Usually the purpose of such acts is to silence dissenters, to obtain information from individuals, or to coerce them to return to their country of origin. These tactics constitute human rights violations,[4] threaten individual rights, and undermine international security.[5] Many of these instances of TNR also violate U.S. law.

Transnational repression takes place all over the world, with an estimated 3.5 million people at risk of being targeted.[6] There have been at least 854 direct attacks of TNR since 2014.[7]

Prolific Perpetrators and Pertinent Cases

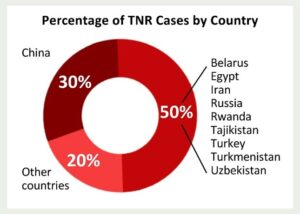

Data sourced from: Michael J. Abramowitz, ‘Transnational Repression: A Global Threat to Rights and Security,’ written testimony, Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing, December 2023.

According to Freedom House, the top ten perpetrators of TNR are China, Turkey, Tajikistan, Egypt, Russia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Iran, Belarus, and Rwanda.[8] China perpetrates the most sophisticated TNR and is responsible for nearly 30 percent of TNR cases worldwide.[9]

China

China’s transnational repression targets dissidents (especially religious and ethnic minorities) through a multitude of repression tools.[10] These include use of technology, geopolitical power, and physical assaults.[11] There have been cases where Chinese officials force Uyghurs to call foreign family members and warn them against engaging in human rights activism.[12] China has sophisticated malware and spyware programs to infiltrate personal electronic devices of overseas diasporas which includes hacking into social media accounts, harassment via email or text, and surveillance of individuals’ locations and cell phone activity.[13]

Most Uyghurs live in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (red)

One of China’s most potent weapons is its immense geopolitical and economic power.[14] It has used this power to gain support of other nations including Russia, Egypt, and India in its practice of TNR.[15] By wielding economic power and influence, China has been able to secure extradition of Uyghurs from foreign countries without going through required channels.[16] Once back in China, these individuals are often subject to indefinite detention in “reeducation camps”, torture, and forced labor.[17]

China has targeted the Uyghurs, a Muslim ethnic minority in northwestern China, since 1997.[18] Those who live within the borders of China are subject to enslavement, torture, sterilization, and rape among other human rights violations.[19] Those who escape are targeted via assassination attempts or the tools discussed above.[20] Recently, a New York City officer was arrested and accused of working in tandem with the CCP to spy on Chinese nationals abroad.[21]

Russia

Russia relies heavily on assassination and other violent repression tools to silence diasporas. The Russian regime is responsible for 7 of 26 assassinations or assassination attempts since 2014. Furthermore, 20 out of the 32 documented cases of physical repression cases are tied to Chechens in the Chechen Republic of Russia.

Chechen Republic (green). Image courtesy of Дагиров Умар is modified and licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Russian citizens in the Chechen Republic are subjected to horrific levels of TNR by provincial leader Ramzan Kadyrov, who is supported by the Kremlin.[22] The Chechen Republic was once an independent area but was overtaken by Russian rule in 2000.[23] Those confined within the borders of the Chechen Republic are subject to brutality, torture, and murder, and those who escape are still victimized by Kadyrov’s regime. In 2009, two Chechen citizens were assassinated in Austria before they were scheduled to testify about torture and executions in the Chechen Republic. In addition, political opponents and critics of Kadyrov who live abroad are assassinated.[24]

Like China, Kadyrov uses extensive surveillance and digital intimidation.[25] The Chechen regime collects information about members of the diaspora who post critiques of the government on social media.[26] Kadyrov uses this information to arrest and torture family members of those dissidents.[27] As recently as 2021, assailants in the Chechen Republic abducted dozens of relatives of activists living abroad.[28] As of February 2024, some of these individuals are still missing.[29]

More broadly, the Russian Federation, headed by President Vladimir Putin, uses violent repression tactics to silence critics abroad.[30] Putin focuses on those living in NATO member nations and those who may have previously engaged in armed conflict against Russia.[31] Like Kadyrov, Putin’s often uses assassination to silence these individuals, relying on radiation and nerve agents.[32] Although the Kremlin denies responsibility for these murders, the radioactive isotopes and nerve agents have been traced back to Russian labs.[33]

Relevant Criminal Statues and Examples of Prosecution

In the US, perpetrators of TNR can be charged under various federal and state criminal statutes. Below are cases recently brought to trial based upon federal law.

18 U.S. Code § 951: Conspiring to Act as an Illegal Agent of a Foreign County

It is a violation of federal law to act in the US as an agent of a foreign government without notifying the U.S. Attorney General, unless one is a diplomat, consular officer, or attaché.[34] Acting as an “agent of a foreign government” means agreeing to operate subject to the direction or control of a foreign government of official.[35]

This statute has been successfully used to prosecute individuals located in the US who are accused of perpetrating transnational repression. On February 18, 2022, Sun Hoi Ying, a Chinese national, was charged for violating § 951.[36] The basis for this charge was a Federal Bureau of Investigation case which uncovered a global plot orchestrated by the CCP to “repress dissent and forcibly repatriate” individuals living legally in the US.[37] Under the code name ‘Operation Fox Hunt,’ Ying allegedly “attempted to threaten and coerce a victim into bending to the [CCP’s] will, even using a co-conspirator who is a member of U.S. law enforcement to reinforce that the victim had no choice but to comply with the [CCP’s] demands.”[38] Through surveillance and threats, Ying attempted to coerce individuals to return to China to face charges.[39] In this case, the CCP held an individual in detention in China while Ying attempted to force their U.S. relative to return to China to face charges.[40] As of August 2024, the case is unresolved .

18 U.S. Code § 2261A: Stalking (Conspiracy to Transmit Interstate Threats/Harassment)

Federal law prohibits a person traveling in interstate or foreign commerce from entering the U.S. with the intent to place under surveillance, kill, injure, harass, or intimidate a person.[41] This includes using the mail, any interactive computer service, or any electronic communication service or system in conduct that (a) places a person in reasonable fear of death or serious bodily injury; or (b) causes, attempts to cause, or would be reasonably expected to cause substantial emotional distress.[42]

An example of the application of this statute is in the case of Qiming Lin, who is accused of conspiracy to commit interstate harassment.[43] Lin worked with the CCP to disrupt a Brooklyn resident’s campaign for U.S. Congress by surveilling and conspiring to physically attack him.[44] The victim, who was a leader of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations in 1989, was able to escape to the US and become a U.S. citizen.[45] Lin worked with a private investigator to obtain the victim’s address and phone number, and Lin also requested that the private investigator find “derogatory information” or manufacture information that would harm the victim’s reputation.[46] Lin then suggested to the private investigator that a beating or “accidental” car crash be orchestrated to deter the victim from running for office.[47] As of August 2024, the case is unresolved.

18 U.S. Code § 1201: Kidnapping

U.S. law prohibits the unlawful seizure, confinement, kidnapping, ransom holding, or abduction except if it is in the case of a minor being subject to such by a parent.[48]

This statute was used to prosecute Iranian nationals accused of plotting to kidnap a U.S. journalist and human rights activist for criticizing the Iranian regime.[49] The defendants surveilled the victim for nearly two years, including installing a live video feed of victim’s home.[50] The defendants then used the victim’s family to attempt to lure the victim to another country in order to capture them.[51] When this was unsuccessful, the defendants planned to use high speed military boats to kidnap the victim to Iran.[52] As of August 2024, the case is unresolved.

Conclusion

Transnational repression poses a grave threat to individual security and inhibits the awareness of human rights abuses worldwide. There are actions that can be taken to combat this epidemic, including recognizing the prevalence of TNR in order to implement preventive policies.[53] Countries can also protect the most vulnerable by respecting their right to asylum and providing refugees with permanent residence status.[54] Finally, targeting perpetrators by imposing sanctions and vetting diplomats hinders TNR.[55] Combating TNR requires cooperation of the international community.

This page was written by Haley M. Bauman, Mitchell Hamline School of Law, spring 2024.

References

[1] Washington Post, “An Eyewitness Reveals How China is Brainwashing the Uyghurs,” April 9, 2023, accessed April 26, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/04/09/uyghur-camps-china-gulbahar-haitiwaji/.

[2] “Transnational Repression,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed April 26, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/counterintelligence/transnational-repression

[3] “Transnational Repression,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed April 26, 2024, https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/counterintelligence/transnational-repression

[4] “’We Will Find You’ – A Global Look at How Governments Repress Nationals Abroad”, Human Rights Watch, February 22, 2024, accessed April 16, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/02/22/we-will-find-you/global-look-how-governments-repress-nationals-abroad

[5] Annie Wilcox Boyajian, “Transnational Repression: A Threat to Rights and Securities in the United States”, Freedom House, January 17, 2024, accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/118/meeting/house/116737/witnesses/HHRG-118-HM05-Wstate-BoyajianA-20240117.pdf

[6] Annie Wilcox Boyajian, “Transnational Repression: A Threat to Rights and Securities in the United States”, Freedom House, January 17, 2024, accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/118/meeting/house/116737/witnesses/HHRG-118-HM05-Wstate-BoyajianA-20240117.pdf

[7] Annie Wilcox Boyajian, “Transnational Repression: A Threat to Rights and Securities in the United States”, Freedom House, January 17, 2024, accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/118/meeting/house/116737/witnesses/HHRG-118-HM05-Wstate-BoyajianA-20240117.pdf

[8] Annie Wilcox Boyajian, “Transnational Repression: A Threat to Rights and Securities in the United States”, Freedom House, January 17, 2024, accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/118/meeting/house/116737/witnesses/HHRG-118-HM05-Wstate-BoyajianA-20240117.pdf

[9] Annie Wilcox Boyajian, “Transnational Repression: A Threat to Rights and Securities in the United States”, Freedom House, January 17, 2024, accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/118/meeting/house/116737/witnesses/HHRG-118-HM05-Wstate-BoyajianA-20240117.pdf

[10] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[11] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[12] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[13] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[14] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[15] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[16] “’We Will Find You’ – A Global Look at How Governments Repress Nationals Abroad”, Human Rights Watch, February 22, 2024, accessed April 16, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/02/22/we-will-find-you/global-look-how-governments-repress-nationals-abroad

[17] “’We Will Find You’ – A Global Look at How Governments Repress Nationals Abroad”, Human Rights Watch, February 22, 2024, accessed April 16, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/02/22/we-will-find-you/global-look-how-governments-repress-nationals-abroad

[18] “Transnational Repression: A Global Problem,” World Without Genocide, October 22, 2022, accessed April 26, 2024, https://worldwithoutgenocide.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Transnational-Repression-10-22-2022.pdf

[19] Christie Wan, “The Persecution of the Uyghurs and Potential International Crimes in China”, Mills Legal Clinic: Stanford Law School, Accessed April 8, 2024.

[20] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[21] “China: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[22] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[23] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[24] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[25] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[26] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[27] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[28] “’We Will Find You’ – A Global Look at How Governments Repress Nationals Abroad”, Human Rights Watch, February 22, 2024, accessed April 16, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/02/22/we-will-find-you/global-look-how-governments-repress-nationals-abroad

[29] “’We Will Find You’ – A Global Look at How Governments Repress Nationals Abroad”, Human Rights Watch, February 22, 2024, accessed April 16, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/02/22/we-will-find-you/global-look-how-governments-repress-nationals-abroad

[30] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[31] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[32] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[33] “Russia: Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study,” Freedom House, accessed April 27,2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/russia

[34] 18 U.S. Code § 951

[35] 18 U.S. Code § 951

[36] “Man Charged with Transnational Repression Campaign While Acting as an Illegal Agent of the Chinese Government in the United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 30, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/man-charged-transnational-repression-campaign-while-acting-illegal-agent-chinese-government

[37] “Man Charged with Transnational Repression Campaign While Acting as an Illegal Agent of the Chinese Government in the United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 30, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/man-charged-transnational-repression-campaign-while-acting-illegal-agent-chinese-government

[38] “Man Charged with Transnational Repression Campaign While Acting as an Illegal Agent of the Chinese Government in the United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 30, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/man-charged-transnational-repression-campaign-while-acting-illegal-agent-chinese-government

[39] “Man Charged with Transnational Repression Campaign While Acting as an Illegal Agent of the Chinese Government in the United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 30, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/man-charged-transnational-repression-campaign-while-acting-illegal-agent-chinese-government

[40] “Man Charged with Transnational Repression Campaign While Acting as an Illegal Agent of the Chinese Government in the United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 30, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/man-charged-transnational-repression-campaign-while-acting-illegal-agent-chinese-government

[41] 18 U.S. Code § 2261A

[42] 18 U.S. Code § 2261A

[43] “Five Individuals Charged Variously with Stalking, Harassing, and Spying on U.S. Residents on Behalf of the PRC Secret Police,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 16, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/five-individuals-charged-variously-stalking-harassing-and-spying-us-residents-behalf-prc-0

[44] “Five Individuals Charged Variously with Stalking, Harassing, and Spying on U.S. Residents on Behalf of the PRC Secret Police,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 16, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/five-individuals-charged-variously-stalking-harassing-and-spying-us-residents-behalf-prc-0

[45] “Five Individuals Charged Variously with Stalking, Harassing, and Spying on U.S. Residents on Behalf of the PRC Secret Police,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 16, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/five-individuals-charged-variously-stalking-harassing-and-spying-us-residents-behalf-prc-0

[46] “Five Individuals Charged Variously with Stalking, Harassing, and Spying on U.S. Residents on Behalf of the PRC Secret Police,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 16, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/five-individuals-charged-variously-stalking-harassing-and-spying-us-residents-behalf-prc-0

[47] “Five Individuals Charged Variously with Stalking, Harassing, and Spying on U.S. Residents on Behalf of the PRC Secret Police,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 16, 2022, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/five-individuals-charged-variously-stalking-harassing-and-spying-us-residents-behalf-prc-0

[48] 18 U.S. Code § 1201

[49] “Iranian Intelligence Officials Indicted on Kidnapping Conspiracy Charges,” U.S. Department of Justice, July 13, 2021, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/iranian-intelligence-officials-indicted-kidnapping-conspiracy-charges#:~:text=Farahani%2C%20Khazein%2C%20Sadeghi%20and%20Noori,of%2020%20years%20in%20prison

[50] “Iranian Intelligence Officials Indicted on Kidnapping Conspiracy Charges,” U.S. Department of Justice, July 13, 2021, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/iranian-intelligence-officials-indicted-kidnapping-conspiracy-charges#:~:text=Farahani%2C%20Khazein%2C%20Sadeghi%20and%20Noori,of%2020%20years%20in%20prison

[51] “Iranian Intelligence Officials Indicted on Kidnapping Conspiracy Charges,” U.S. Department of Justice, July 13, 2021, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/iranian-intelligence-officials-indicted-kidnapping-conspiracy-charges#:~:text=Farahani%2C%20Khazein%2C%20Sadeghi%20and%20Noori,of%2020%20years%20in%20prison

[52] “Iranian Intelligence Officials Indicted on Kidnapping Conspiracy Charges,” U.S. Department of Justice, July 13, 2021, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/iranian-intelligence-officials-indicted-kidnapping-conspiracy-charges#:~:text=Farahani%2C%20Khazein%2C%20Sadeghi%20and%20Noori,of%2020%20years%20in%20prison

[53] “Transnational Repression”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression

[54] “Transnational Repression”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression

[55] “Transnational Repression”, Freedom House, accessed April 27, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression