The Yugoslav War is often referred to as the deadliest conflict in Europe since World War II. According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, from 1991-1999, about 140,000 people lost their lives and about 4 million other were displaced as political refugees.[1] In response to this conflict, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was formed.

The ICTY, a United Nations court, was established by Resolution 827 of the United Nations Security Council in May 1993. It was the first war crimes court ever created by the United Nations and the first international war crimes tribunal since the tribunal held in Nuremberg in 1946 after World War II. [2] This court was set up to prosecute serious crimes committed during the war in the former Yugoslavia and to try its chief organizers, planners, and perpetrators. The Court’s indictments addressed crimes committed from 1991 to 2001 against members of various ethnic groups in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. The proceedings at the ICTY prosecuted people on two levels: (1) individual acts; and (2) in a position of authority for acts to be carried out.[3]

The Tribunal indicted 161 individuals for crimes committed against thousands of victims during the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. While the biggest numbers of cases were against Serbs or Bosnian Serbs, charges were also brought against defendants of other ethnic groups, including Croats, Bosnian Muslims and Kosovo Albanians, for crimes committed against Serbs.[4] The court completed its last case in 2017 and officially closed on December 21, 2017.

The Yugoslav tribunal was a unique court often referred to as a hybrid court, because it combined elements of the Anglo-American common-law adversarial system and the European civil law system. In our common-law system, factual determinations are driven by lawyers, with a judge perceived as an impartial figure of authority. The rules of evidence assume that most cases will be submitted to juries, whose members must be shielded from evidence that might lead them to erroneous conclusions. In the civil-law system, factual determinations are driven by the judge, who decides which witnesses to hear after all the evidence has been submitted in a dossier. Little evidence is presented in court because, as a professional, the judge is trusted to sort out the relevant evidence and give it the appropriate weight.

One of the best features of the adversarial system in the hybrid court is the cross-examination of witnesses. The best feature of the civil-law approach in the court is the judge’s determination to resolve all ambiguities. The guilt of the accused must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt in cases brought to the tribunal. Evidence that is brought in is also treated fairly differently, as evidentiary issues are to be addressed in terms of weight rather than admissibility. Very little evidence is excluded, but a lawyer must anticipate how to persuade the judges to give evidence the weight he or she thinks appropriate.

The Yugoslavia tribunal combined facets of both systems, as the judges and lawyers who populated the court came from both common-law and civil-law traditions in almost equal proportions. The sixteen permanent judges were elected by the United Nations General Assembly. Most were professional judges who rose to the highest ranks of judicial office in their home countries, with an occasional academic or diplomat included.

![]()

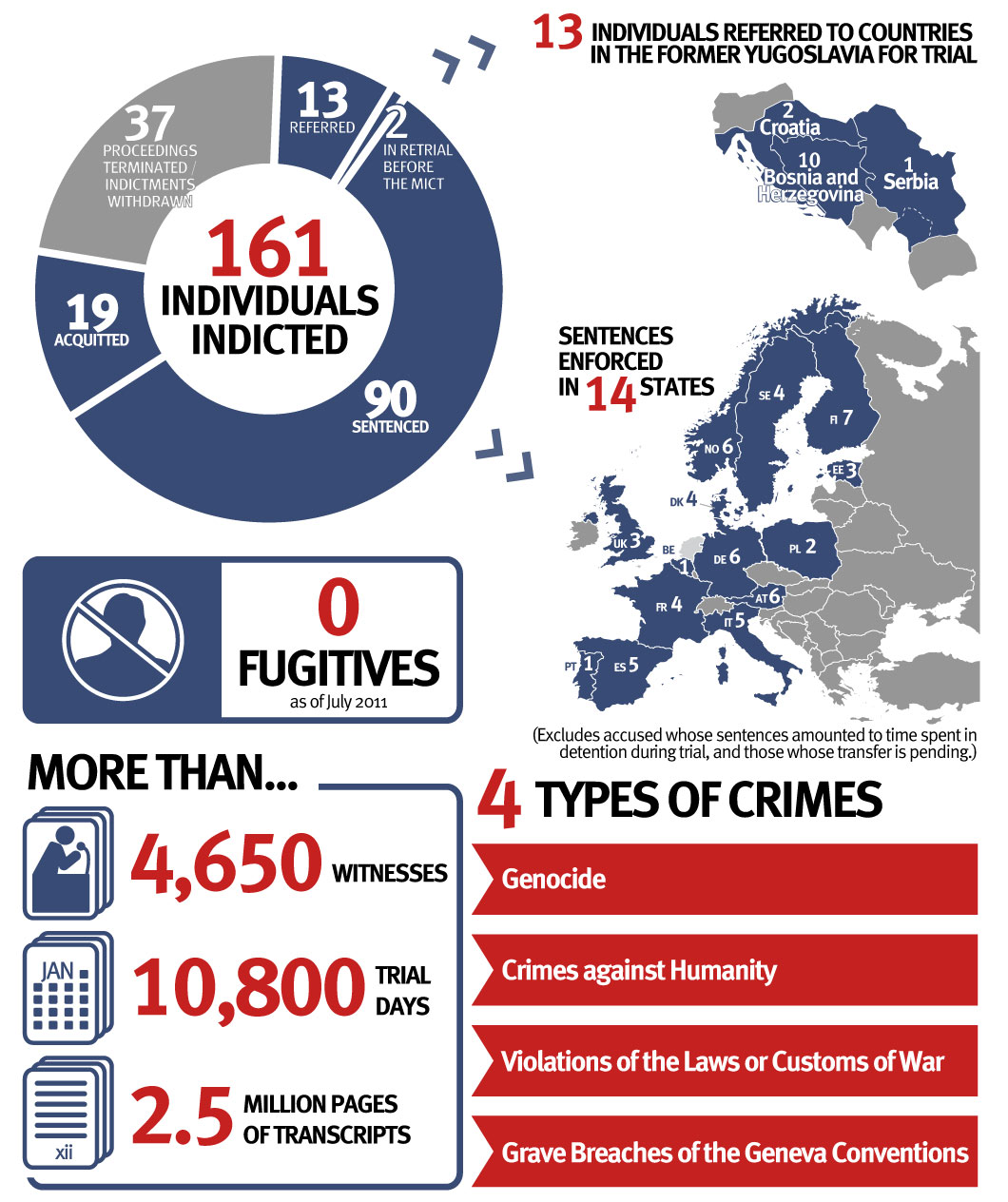

- 161 people were indicted

- 90 were convicted and sentenced

- 19 were acquitted

- 13 were referred to national jurisdictions (Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina) for trial

- 20 indictments were withdrawn, 10 died before transfer to tribunal, 7 died after transfer to tribunal

- 2 appeals cases are before the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT)

Politically notable cases include the indictments of Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, Ratko Mladic, and Radovan Karadzic.

Slobodan Milosevic was the former Serbian and former Yugoslavian president. He was “[i]ndicted for genocide; complicity in genocide; deportation; murder; persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds; inhumane acts/forcible transfer; extermination; imprisonment; torture; willful killing; unlawful confinement; willfully causing great suffering; unlawful deportation or transfer; extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly; cruel treatment; plunder of public or private property; attacks on civilians; destruction or willful damage done to historic monuments and institutions dedicated to education or religion; [and] unlawful attacks on civilian objects” (ICTY case).

Among other charges, he was accused of murdering hundreds of Kosovo Albanian citizens, deliberate destruction of their property, and systematic sexual assaults against them, particularly women. He was accused of murdering hundreds of Croat civilians, routine imprisonment of thousands of Croat civilians under inhumane conditions, repeated torture in detention facilities, and deliberate destruction of their property. He was accused of murdering thousands of Bosnian Muslims, detention, often resulting in death, of thousands of Bosnian Muslims, creating conditions of forced starvation, numerous massacres of Bosnian Muslim citizens, deliberate destruction of their property, and enforcing restrictive and discriminatory measures against Bosnian Muslims.

He died on March 11, 2006 and his case at the ICTY was terminated on March 14, 2006.

Ratko Mladic was Commander of the Bosnian Serb Army between 1992 and 1996. He faced charges of “genocide, persecutions, extermination, murder, deportation, inhumane acts, terror, unlawful attacks, [and] taking of hostages” (ICTY case).

Most notably, he is accused of creating a campaign of sniping and shelling civilians in Sarajevo, designed to terrorize residents and of commanding the Srebrenica massacre, a mass killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys in 1995 by the Army of Republika Srpska.

His trial began in May 2012. The prosecution concluded in February 2014, and the defense’s case began in May 2014. On November 22, 2017 Ratko Mladic was found guilty of genocide, five counts of crimes against humanity, and four counts of violating the laws or customs of war. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Radovan Karadzic was a founding member of the Serbian Democratic Party and President of Republika Srpska (formerly the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina) and commander of its armed forces. He faces charges of “genocide, extermination, murder, persecutions, deportation, inhumane acts, acts of violence the primary purpose of which was to spread terror among the civilian population, unlawful attack on civilians, [and] taking of hostages” (ICTY case).

Most notably, he was accused of developing a systematic shelling and sniper campaign designed to terrorize residents of Sarajevo, detainment of UN peacekeepers in May and June 1995, and a commanding role in the Srebrenica massacre. He was accused of planning, instigating, and aiding genocide against the Bosnian Muslim and Bosnian Croat national, ethnic, and/or religious group.

His trial began in March 2010; the prosecution rested their case in May 2012. The defense began their case in October 2012. He was sentenced to 40 years imprisonment in March 2016. He was convicted of genocide, crimes against humanity, and violations of the laws or customs of war.

Implications for Justice and Impunity

The International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia has contributed to justice in many ways because it accomplished exactly what it was intended to do. One of the most important ways the ICTY has contributed to the broader issues of impunity and transitional justice was in fact to hold the political leaders of Yugoslavia accountable.

Transitional justice refers to the set of judicial and non-judicial measures that have been implemented by different countries in order to redress the legacies of massive human rights abuses. These measures include criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations programs, and various kinds of institutional reforms. [5] The elements of a comprehensive transitional justice policy are:

- Criminal prosecutions, particularly those that address perpetrators considered to be the most responsible.

- Reparations, through which governments recognize and take steps to address the harms suffered. Such initiatives often have material elements (such as cash payments or health services) as well as symbolic aspects (such as public apologies or day of remembrance).

- Institutional reform of abusive state institutions such as armed forces, police and courts, to dismantle—by appropriate means—the structural machinery of abuses and prevent recurrence of serious human rights abuses and impunity.

- Truth commissions or other means to investigate and report on systematic patterns of abuse, recommend changes and help understand the underlying causes of serious human rights violations.

The Tribunal laid the foundations for what is now the accepted norm for conflict resolution and post-conflict development across the globe, specifically that leaders suspected of mass crimes will face justice. Also, by holding leaders accountable, the Tribunal dismantled the tradition of impunity for war crimes. The Tribunal indicted individuals on all levels of government, including heads of state, prime ministers, army chiefs of staff, and government ministers from various parties of Yugoslavia.[6] As these individuals were brought to justice, the country, its citizens, its victims, and its diaspora could at last have finality and move on with their lives.

Not only did the ICTY convict prominent individuals who committed heinous crimes, but it also provided the victims, and especially hundreds of Yugoslav women who have been raped, an opportunity to voice the horrors they witnessed and experienced. The Tribunal allowed them to be heard and to speak about what had happened to them and their families. A final achievement of the ICTY is that the Tribunal helped in creating an accurate historical record of the war. It contributed in establishing the facts of the events, which has helped to bring peace and closure to the victims.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia was also very important in developing the field of international law, as it proved that efficient and transparent international justice is possible.[7] Some of the success of the Tribunal has inspired and motivated the creation of other international criminal courts such as the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the Special Court for Sierra Leone. National courts set up in Kosovo, East Timor, and Lebanon to deal with war crimes also borrowed heavily from the Yugoslav tribunal. The ICTY Tribunal has been a great model for the implementation of mechanisms such as giving due process to the accused and court’s ability to promote peace in the areas affected by conflict for other nations and other Tribunals to follow.[8] Although the Court did much to bring about peace and develop international law, many victims voices and claims have not been met.

For more information, visit www.icty.org.

This page was written jointly by Christie Nicoson, Former Program and Operations Coordinator, Lisa Dailey, Former News Associate, and Rachel Hall Beecroft, Former Program and Operations Coordinator. This page was updated 01/09/18.

Download a one page PDF summary of this information here.

Resources:

[1] “Transitional Justice in the Former Yugoslavia.” International Center for Transitional Justice. 1 January 2009. http://ictj.org/sites/files/ICTJ-FormerYugoslavia-Justice-Facts-2009. (accessed 27 March 2014).

[2] “About the ICTY.” United Nations: International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (UNICTY), http://www.icty.org/en/about (accessed 13 April 2014).

[3] “About the ICTY.” United Nations: International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (UNICTY).

[4] Rick Gladstone, Denouncing Serbian Tilt, U.S. Boycotts U.N. Meeting (New York Times, April 10, 2013).

[6]“Achievements,” ICTY – TPIY.

[7] “About the ICTY,” ICTY – TPIY, N.p., n.d.. http://www.icty.org/en/about (accessed 16 Apr. 2014).

[8] “ICTY Judge discusses challenges of international criminal court, tribunals,”