The genocide in Argentina, often referred to as the ‘Dirty War,’ was a targeted campaign by the Argentine government to wipe out suspected dissidents and subversives. In seven years, around 30,000 Argentinians were killed or forcibly disappeared. Citizens were arrested and tortured. Assassinations were carried out by torture and mass shootings. People were captured and put onto ‘death flights’ and thrown from airplanes into the Atlantic Ocean or the Rio de la Plata, where they drowned. [1]

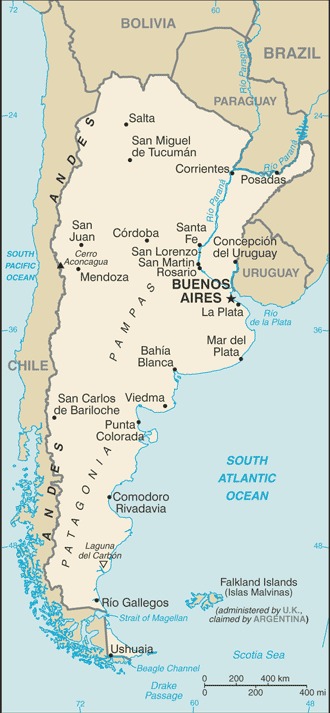

Argentina is South America’s south-easternmost country and is bordered by Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and the South Atlantic Ocean. Argentina is four times the size of Texas and is the second largest country in South America.

Argentina is South America’s south-easternmost country and is bordered by Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and the South Atlantic Ocean. Argentina is four times the size of Texas and is the second largest country in South America.

Political Instability

Juan Peron was elected president of Argentina in 1946. Peron sought to industrialize Argentina and to provide economic and social benefits to the working classes and the poor. He nationalized the railroads, funded public works projects, and provided wage increases and benefits to industrial workers. [2] This brought Peron unwavering support from millions of laborers, known as descamisados, or ‘shirtless ones.’

Peron was overthrown in 1955 and went into exile. In 1971 the Peronist party was re-established, and Peronist candidates won the presidential election the following year. Juan Peron returned to Argentina and was elected as president in a special election. [3] In 1974, Peron died; his wife Isabel assumed power. Terrorism from both the right and the left escalated, leaving hundreds of people dead. By 1975 inflation had risen to 300% and protests and demonstrations broke out over economic conditions. [4]

Juan Peron and his beloved first wife, Evita, give a speech to the descamisados at Plaza de Mayo on May 1, 1952.

Argentina had been plagued by political instability, military rule, and a crumbling economy for decades. In 1976, General Jorge Videla took advantage of these conditions, seizing power and establishing a military junta, or dictatorship. Videla planned on reforming Argentinian society to fit his ultra-conservative, militarized, Catholic vision of what the country should be, and soon the government began waging a war on any potential opposition. [5] Videla sought to eliminate Peronists, socialists, and anyone with left-wing ideals, all of whom were perceived as a threat to his leadership. The government forcibly disappeared and murdered 30,000 people throughout the junta’s brutal campaign.

In 1982, the junta was losing support because of human rights abuses and economic mismanagement. Inflation reached 900%. [6] In need of a win, Argentina invaded and claimed sovereignty over the Falkland Islands, two British colonial territories in the South Atlantic that had long been disputed. The move worked initially, and large crowds began to gather at the Plaza de Mayo, a central square in front of Argentina’s presidential palace, to demonstrate support for the military initiative. The Falkland conflict lasted for 74 days and ended with Argentina’s surrender on June 14, 1982. At least 650 Argentine and 255 British lives were lost. [7] The outcome prompted large protests against the government and ultimately led to its demise. In 1983, the government returned to civilian control, marking the end of the seven-year genocide.

The military regime set out to reform society through its Process of National Reorganization called El Proceso, which focused on the elimination of perceived subversion, improvement of the economy, and the creation of a new national framework. [8] Subversion to the regime included not just guerrilla movements but any form of dissent in the school, family, factory, arts, or culture. Building a new national framework required the eradication of all subversives, and students, trade unionists, journalists, artists, militants, Peronists, and anyone suspected of being a left-wing activist were targeted.

Pirámide de Mayo in Buenos Airea covered with photos of the disappeared, known as desaparecidos. Image by WikiLaurent| Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) | License

Tens of thousands of Argentinians were forcibly disappeared, taken from their homes, jobs, or off the street never to be seen again. They were taken to detention centers and tortured by death squads, some for several months. Rape was commonly used against women. Many were killed in mass shootings. Others were taken on ‘death flights’ and pushed from an airplane to their death in the South Atlantic or the River Plata. Bodies were cremated, buried in mass graves, or disposed of in rivers and the ocean. Residents of the Parana River Delta frequently saw military planes dumping packages into the river. Some of the packages washed ashore, leaving residents in shock when they found dead bodies inside. [9]

Some of the disappeared women were pregnant and others had small children. The pregnant captives were kept alive long enough to give birth. The women were then murdered, and their babies were sold or given to military or other families deemed “politically acceptable.” Birth certificates of nearly 500 babies were falsified and the babies’ true identities were erased. In some cases, the babies were given to the same people who had killed the parents. [10]

In 1977, the mothers and grandmothers of the disappeared formed Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo and Las Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, the mothers and grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo. Every Thursday, continuing so far to the year 2020, they march in silent protest around the plaza, the mothers seeking answers to what happened to their children and the grandmothers the identities and locations of their stolen grandchildren.

In 1987, the Abuelas began storing their DNA profiles in a newly created genetic bank, hoping to find their missing grandchildren through DNA matching, and in 1992 the government created the National Committee for the Right to Identify (CONADI). [11] The organization assists young adults in obtaining DNA analysis and in investigating documents that could link them to their birth families. [12] As of September 2019, 130 children have been identified. In 2018, the Abuelaswere nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. [13]

The Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. Image by Archivo Hasenberg-Quaretti| Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) | License

Unfortunately, the government’s use of cremation and the dumping of bodies into rivers and oceans has prevented the recovery of the remains of many of the disappeared. Out of 30,000 disappearances, fewer than 1,000 bodies have been found and identified by anthropologists. [14]

U.S. Response

Although the United States did not play a direct role in the ‘Dirty War’ as it has in other conflicts, its response to the atrocities was almost nonexistent and, in some cases, supportive of the brutal regime in the name of the larger Cold War against communism. After Videla established the military junta in 1976 and began cracking down on left-wing “terrorists,” U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told Argentina’s foreign minister, “If there are things that have to be done, you should do them quickly.” The American ambassador to Argentina reported to Washington that the Argentine government interpreted Kissinger’s words as a “green light” to continue its atrocities against left-wing subversives. [15]

In 2016, the Obama administration announced its initiation of The Argentina Declassification Project where more than 1,000 documents relating to U.S. policy toward the ‘Dirty War’ were declassified and released. The documents date from President Jimmy Carter’s administration and reveal conflicting efforts to push forward on human rights, Carter’s principal foreign policy agenda, and to prevent Argentina from a closer relationship with the Soviet Union by cutting off aid and trade. [16] The U.S. administration at that time did cut ties with Argentina’s junta, but Cold War pressures took precedence and economic relationships were restored.

As of April of 2019, the fourth and final collection of documents were released. These documents now total over 11,000 pages and reveal the “circumstances of the crimes committed by the junta” and U.S. knowledge of the crimes. [23]

Justice Process

Like many other Latin American nations, the justice process in Argentina has been slow and challenging. Despite this, prosecutors continue to seek truth and justice for Argentina’s victims. After democracy returned to the country in 1983, then-President Raul Alfonsin began investigating and prosecuting members of the military junta. In 1985, former dictator General Jorge Videla and Admiral Emilio Massera, thought to be the masterminds behind the ‘Dirty War,’ were sentenced to life imprisonment for their roles in the genocide. Nine senior military members of the junta were convicted during Alfonsin’s presidency. [17]

However, in 1986, under pressure from the military, Argentina’s Congress passed the Full Stop and Due Obedience laws, which effectively stopped the prosecution of human rights violations committed during the dictatorship. In 1990, President Carlos Menem pardoned Videla, Massera, and the rest of the convicted junta members. [18]

In 2003, the Argentine Congress passed a law revoking the 1990 amnesty laws, and in 2005 the Supreme Court ruled that the amnesty laws were unconstitutional and that no statute of limitations applies to crimes against humanity, the crimes that were alleged to be perpetrated by the junta. [19] This removed the last hurdle to trying perpetrators, and prosecutions were resumed.

As of March 2019, the Attorney General’s Office has charged 3,161 people of crimes during this period, convicted 901, and acquitted 142 of the accused. Of 611 cases alleging crimes against humanity, 221 rulings have been issued. [20] The remaining cases are ongoing. The large number of victims, suspects, and cases makes it difficult to prosecute perpetrators in a timely manner while respecting their due process rights, and the courts have come under criticism for delaying cases. The courts have also been criticized for handing down lenient sentences. More than half of the aging prisoners (650 of them) are under house arrest, which is a legal right for people over age 70 under Argentine law. [21]

In 2015, the Argentine government began dismantling official bodies dedicated to reviewing documents to provide as evidence to the courts, a move denounced by human rights groups. Author and genocide scholar Dr. Daniel Feierstein noted, “It would appear that a new judicial climate has been created which has led many courts to easily grant house arrest to those guilty of genocide, significantly increase the number of acquittals, and reject preventive detention at a time when its use is on the rise for less serious crimes.” [22].

Although challenges remain and the process is slow, Argentinians continue to demand justice for those who were disappeared. Four decades later, the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo continue to march. Lost grandchildren are still being reunited with their biological families, and convictions are being handed down to the genocide’s worst perpetrators.

Looking forward, even 37 years later, Argentina is continuing its slow progress in charging and trying individuals for their crimes during the ‘Dirty War.’ DNA tests are also very slowly helping to identify children in relation to their birth families despite rapid increases in DNA testing in past years.

Finally, there have been ongoing human rights violations in recent years, ranging from police abuses to violence against women. In October of 2019, Alberto Fernández was elected president of Argentina. During his campaign, he promised a commitment to defending democracy and human rights. Whether he will follow through on this promise remains to be seen. [24] The economic situation in 2020, with inflation over 50%, official unemployment at 10%, and declining per capita GDP, plus the added instability of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, portend a difficult base from which to increase human rights protections. [25]

Updated: World Without Genocide, April 2020

_______________

[1] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/3673470/Argentinas-dirty-war-the-museum-of-horrors.html

[2] https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/argentina

[3] Refer to Note 2

[4] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/1196005.stm

[5] https://madresdemayo.wordpress.com/the-dirty-war/

[6] Refer to Note 5

[7] https://www.britannica.com/event/Falkland-Islands-War

[8] https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/argentina.htm

[9] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-21884147

[10] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/12/us/children-of-argentinas-disappeared-reclaim-past-with-help.html

[11] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/children-argentinas-disappeared-reunited-birth-families

[12] https://madresdemayo.wordpress.com/las-madres/las-abuelas/

[14] Refer to Note 9

[15] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/17/opinion/americas-role-in-argentinas-dirty-war.html

[18] Refer to Note 17

[19] Refer to Note 17

[20] https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/argentina#befd9b

[21] Refer to Note 17

[22] Refer to Note 17

[23] https://apnews.com/8b9822e4f9b740448b4b95132fac4011

[24] https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/news-columns-blogs/andres oppenheimer/article238238009.html

©2020 World Without Genocide