International Criminal Tribunals: A Path towards Justice

Prepared by Michelle Johnson, Megan Manion, Alejandra Sanchez, and Sarah Schmidt

Benjamin B. Ferencz Fellows in Human Rights and the Law

Introduction. In the aftermath of genocides and other atrocity crimes in the 20th century, the United Nations created several ad hoc, or temporary, tribunals to investigate the crimes and to prosecute the perpetrators. These tribunals are part of transitional justice, the effort to move a society forward after horrific violence, to reinstate the just rule of law, and to provide victims with some form of compensation for the harm that happened to them in body, mind, and culture.

Holding trials is only one form of transitional justice. Other strategies include awarding financial reparations, either to individuals or communities; establishing memorials and monuments; holding truth and reconciliation councils; and implementing steps to prevent recurrence of violence through institutional reforms of the local judiciary, police systems, and access to civil society.

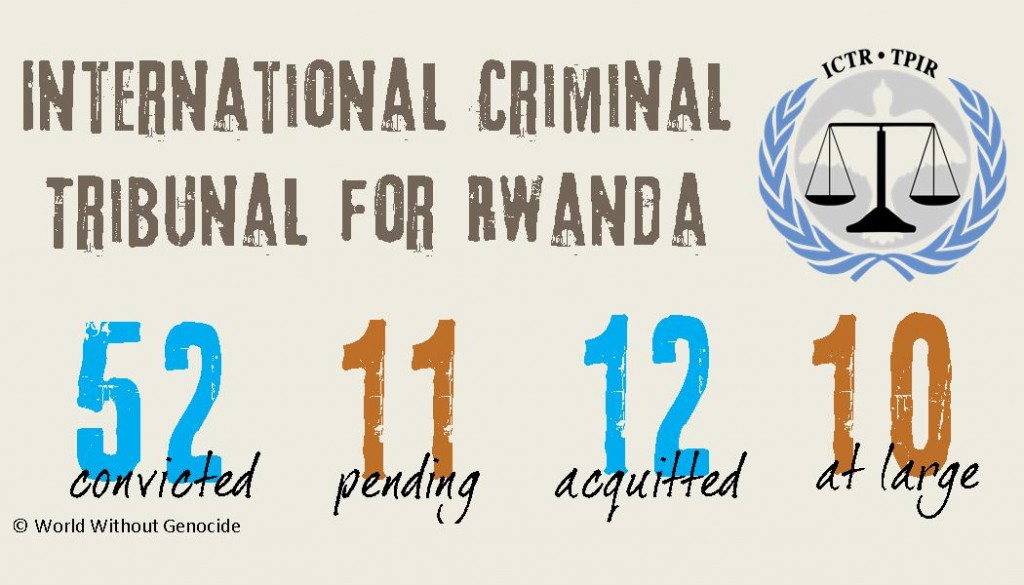

International Criminal Tribunal Rwanda (ICTR): This Tribunal was established in 1994 as an ad hoccourt solely to investigate the crimes associated with the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. The Tribunal has been held in Arusha, Tanzania and is nearing the end of its mandate. All trials and appeals are concluded except the final appeal from the case of Nyiramasukuko et al., also known as the “Butare” case. Oral arguments for the

six defendants were held in April 2015 and the final judgment is expected to be delivered near the end of 2015. Formal closure of the Tribunal is planned for the end of 2015.

The Tribunal continues to address three significant projects before closing the doors. The first includes monitoring the issue of reparations. The International Organization for Migration has submitted a draft assessment study to the Rwandan Government on issues of reparations. Secondly, the issue of relocating the accused and released convicted persons still residing in Arusha has been passed from the Tribunal to the United Nations Mechanism for International Tribunals. Lastly, in May 2015, four cases were determined to involve contempt/false testimony before the Tribunal. All suspects remain at large. Special benches have been assigned to review the indictments to determine if any action is necessary prior to the Tribunal’s closure to preserve the possibility of charges being prosecut4ed by the mechanism.

The legacy of ICTR. Judge Vagn Joensen, President of the International Tribunal for Rwanda, appeared at the UN General Assembly to reflect on the Tribunal’s legacy. Judge Joensen discussed the substantial body of jurisprudence created over the past two decades. He emphasized that the ICTR has codified facets of international criminal law and international humanitarian law that were, at the time of the Tribunal’s creation in 1994, either undeveloped or non-existent. President Joensen emphasized that the ICTR has been at the forefront of many firsts, including the first conviction by an international court for the crime of genocide, the first conviction for rape and sexual violence as a form of genocide by an international court, and the first court to hand down a judgment against a Head of Government since the Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals.

President Joensen concluded by stating, “The ICTR’s legacy is made up of the voice it provided to the countless victims and survivors of the Rwandan Genocide, the vast contributions it made to the development of international law, and the initiatives it created to ensure that the world it left behind was stronger and better equipped to continue and hopefully, someday soon, end the fight against impunity once and for all.”

Since its opening in 1995, the Tribunal has indicted 93 individuals for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Rwanda in 1994. Those indicted include high-ranking military and government officials, politicians, businessmen, and religious, militia, and media leaders. Of the 93 individuals indicted, 61 were sentenced, 14 were acquitted, 10 were referred to national jurisdictions for trial, 3 were deceased prior to or during trial, 3 fugitives were referred to the MICT, and 2 indictments were withdrawn before trial.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY): This ad hocTribunal was created to address the crimes perpetrated in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. The proceedings have been held in The Hague, Netherlands and the Tribunal is expected to complete operations in two years. In 2015, the Tribunal delivered two major judgments: the Popovic et al. case and Tolimir appeal. One more appeal judgment in the

Stanisic and Simatovic case is expected by the end of the year. Only four trials and two appeals will be ongoing at the beginning of 2016, two trials will completed by the first quarter of the new year, one additional trial and one appeal will be completed during the remainder of 2016, and the two last cases will be completed before the end of 2017.

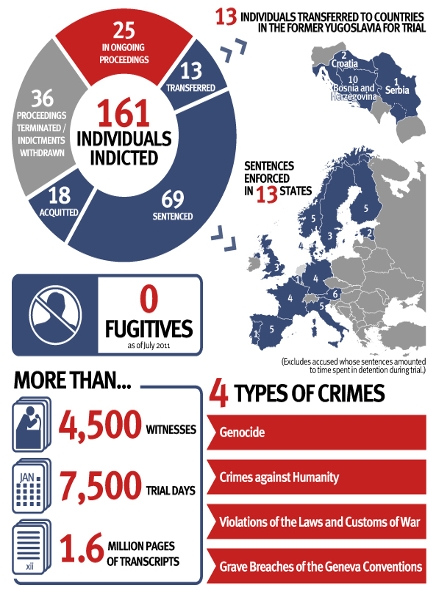

The UN Security Council established the ICTY in May 1993. The first indictment was issued in November 1994 against Dragan Nikolic, a commander of the Susica detention camp in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, for crimes committed against non-Serb civilians in 1992. Since its establishment, the Tribunal has indicted 161 individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, violation of the laws or customs of war, and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. Of the 161 individuals indicted, 80 were sentenced, 18 were acquitted, 13 were referred to countries in the former Yugoslavia for trial, and 36 indictments were terminated or withdrawn.

The UN Security Council established the ICTY in May 1993. The first indictment was issued in November 1994 against Dragan Nikolic, a commander of the Susica detention camp in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, for crimes committed against non-Serb civilians in 1992. Since its establishment, the Tribunal has indicted 161 individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, violation of the laws or customs of war, and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. Of the 161 individuals indicted, 80 were sentenced, 18 were acquitted, 13 were referred to countries in the former Yugoslavia for trial, and 36 indictments were terminated or withdrawn.

Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL): Charles Taylor, the former President of Liberia, was convicted by this court of eleven counts of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other serious violations of international humanitarian law. In April 2012, the SCSL made history when Taylor became the first African head of state to be convicted for his role in war crimes.

He will serve the remainder of his 50-year prison sentence in the United Kingdom after Court President Justice Philip N. Waki denied his application to appeal. Additionally, Justice Waki dismissed Taylor’s motion

SCSL Logo (Wikipedia 10-30-2015)

asking that he be transferred to Rwanda where the other SCSL convicts are imprisoned.

In January 2002, the UN and the government of Sierra Leone signed an agreement establishing the Special Court for Sierra Leone, to be held in Freetown, Sierra Leone, to try those responsible for crimes during the Sierra Leone Civil War. The first set of indictments was issued in March 2003. Since its establishment, the SCSL has indicted 22 individuals. Thirteen of these individuals were indicted for crimes against humanity, violation of the laws or customs of war, and other violations of international humanitarian laws. The remaining nine were charged with contempt of court charges. The first contempt case in 2005 involved witness intimidation by a defense investigator and four of the defendants’ wives. The second case in 2011 involved witness tampering and interference with the administration of justice. Of the 22 indicted individuals, 16 were sentenced, 2 were acquitted, 3 were deceased prior to trial, and one individual remains a fugitive.

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC): Starting on September 7, 2015, the Trial Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia heard evidence related to charges of genocide in Case 002/02 against Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea, which focuses on allegations related to the treatment of the Cham group. Fourteen witnesses and one expert are scheduled to testify during this part of the trial.

The Cham are an ethnic minority within Cambodia who share a common language, a common culture, and a common religion of Islam. According to the closing order, people who belonged to the Cham group were systemically killed and the Communist Party of Kampuchea implemented a policy to destroy, in whole or in part, the Cham group as such. The Order states that the Cham were systemically and methodically targeted and killed on account of their membership in the Cham group and were forcibly moved and dispersed into Khmer villages and prohibited from practicing their religion. Cham religious leaders, elders, and those who continued to practice their religion were imprisoned and killed. Cham culture, language and dress were further prohibited. Evidence reflects that 36% of the Cham people in Cambodia died during the regime of Democratic Kampuchea.

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), commonly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, is located in Phnom Penh, Cambodia to try the most senior members of the Khmer Rouge for violations of international law and the 1956 Penal Code of Cambodia perpetrated during the Cambodian genocide, 1975-1979. It is primarily a national court, established as part of an agreement between the Royal Government of Cambodia and the UN, and its members include both Cambodian and foreign Judges. The ECCC is considered a hybrid court, created by the Cambodian government in conjunction with but independent of the UN. The primary purpose of the tribunal is to provide justice to the Cambodian people who were victims of the Khmer Rouge regime’s policies. Additionally, rehabilitative victim support and media outreach are also important goals of the tribunal.

Since 2007, the tribunal has issued five indictments against five individuals. Three of the five individuals have been sentenced; one died prior to trial; and one indictment was suspended before trial.

The International Criminal Court was officially created on July 17, 1998 when the international community marked a new achievement in the mission to end impunity for the gravest violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. On that day, 120 States adopted the Rome Statute, the legal basis of the International Criminal Court. The Rome Statute entered into force on July, 1 2002 after sixty countries ratified the document, making the ICC the first-ever permanent court of its kind. It is an independent international organization distinct from the United Nations and other ad hoc and regional international tribunals. Its core and foundational principles rely on the robust commitment of the international community to provide permanent modes of accountability and justice for the worst violations of human rights and humanitarian law.

The Court currently has 23 cases pending (as of October 2015). The first case was concluded on March 14, 2012, with the conviction of Thomas Lubanga Dyilo for the war crime of conscripting, enlisting, and using children under the age of fifteen in soldiers in armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Other cases include charges of murder and attempted murder; attacking civilians; rape; sexual slavery of civilians; pillaging; displacement of civilians; persecution; and other inhumane acts. In addition to the cases in proceedings, the Chief Prosecutor of the ICC, Ms. Fatou Bensouda, maintains a heavy document of investigations. Conflicts in countries or regions under investigation include Mali, Cote D’Ivoire, Libya, Kenya, Central African Republic, Darfur, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Uganda. In June, 2015, Palestine submitted a request for investigation into the war between Hamas and Israel in the summer of 2014.

Jurisdiction and Reach. While the Court has many situations, investigations, and cases within its mandate, the Court’s jurisdiction is limited to three specific crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. A fourth crime, that of aggression, is currently being negotiated and framed for future prosecution. The three pathways to jurisdiction require that: 1) the accused is a national of a State Party or a State that accepts the jurisdiction of the Court; 2) the crime took place on the territory of a State Party or a State accepting the jurisdiction of the Court; or 3) the United Nations Security Council referred a situation to the Chief Prosecutor. The Court’s jurisdiction is also limited by the principle of complementarity, meaning that the Court only takes on a case if the state is unwilling or unable to do so.

US Involvement in the ICC. The United States has not yet ratified the Rome Statute, despite the almost-global support for the Court. The Bush Administration actively opposed the International Criminal Court and “unsigned” the Rome Statute, which had been signed by President Clinton in 2000, the first step towards its ratification. Hilary Clinton, when Secretary of State in 2009, said it is a “great regret” that the US is not a member of the ICC. The United States has since developed a positive relationship with the Court by offering its non-member observer state support.

CEDAW[1] . CEDAW is the acronym for the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women. This Convention was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1979 and provides action steps and guidelines for States to follow in their efforts to end gender-based discrimination. CEDAW defines discrimination against women as “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.”[2] States that have ratified or acceded to CEDAW are required to submit a national report every four years to the CEDAW Committee, composed of twenty-three independent experts from around the world, which provides information about measures taken to meet the treaty’s obligations.

To date (fall 2015) 187 countries have ratified CEDAW. The United States is one of six countries that have not yet done so; the others are Sudan, South Sudan, Tonga, Palau, and Iran. There are currently more than 150 US organizations that support and advocate for US ratification of CEDAW.

The CEDAW Committee in 2015 will review national reports submitted by the Russian Federation, Portugal, Liberia, Slovenia, Lebanon, Uzbekistan, United Arab Emirates, Malawi, Madagascar, Timor-Leste and Slovakia.[3] Additionally, the Committee is examining “synergies between the political framework of UNSCR 1325 (2000) and follow-up resolutions on Women, Peace, and Security and CEDAW General Recommendation No. 30 (2013) on Women in Conflict Prevention, Conflict, and Post-Conflict Situations.”[4] The ongoing focus is on integrating a human rights element in the Women, Peace, and Security agenda of the Security Council and the role that CEDAW can play within that framework.

UN 1325[5]. UN Security Council Resolution 1325 was adopted in 2000 and addresses women’s role in peacemaking and peacekeeping processes. UN1325 emphasizes the importance of involving women as equal participants, in numbers and in function, in preventing and resolving conflict, “peace negotiations, peace-building, peacekeeping, humanitarian response and in post-conflict reconstruction.”[6] Under this resolution, states are also tasked with taking measures to ensure women and girls’ safety and security from gender-based violence, especially during times of armed conflict.

On October 14, 2015, the UN Security Council adopted an updated version of UN 1325 and recommended doubling the number of women involved in all aspects of the peace process. This new and improved version expresses the intention “to dedicate periodic Council consultations on country situations, as necessary, to the topic of women, peace, and security implementation, as well as the intention to ensure that Security Council missions take into account gender considerations and the rights of women.”[7] The 2015 UN1325 also emphasizes the accountability of all actors, especially in the combating of violent extremism. The Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC), located in Teshie, Accra, Ghana, also commemorated the 15th anniversary of UN 1325. The KAIPTC held a four-day workshop that addressed Women, Peace, and Security topics with special training on election observation and dispute resolution, pertinent topics in Africa. The conference was held with the support of the African Union Commission.[8]

Women’s Leadership at the International Criminal Court

Thirteen years after entering into force, the International Criminal Court has elected its first female President, Judge Silvia Alejandra Fernández de Gurmendi from Argentina. What makes this historic event even more remarkable is that the elected First and Second Vice Presidents are also female judges. With Fatou Bensouda presiding as Chief Prosecutor since 2012, all the leading positions of the court are now held by women.

This change in leadership is particularly significant in cases dealing with issues of gender violence and rape. Some of these issues have been brought to the forefront in decisions influenced by women such as Navi Pillay. While she was a judge at the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia, her attention to evidence presented regarding acts of sexual violence against Tutsi women led to the inclusion of rape as an act of genocide[9] in the judgment against Jean-Paul Akayesu[10].

Additionally, this past International Women’s Day, March 8, 2015, the ICC reaffirmed its commitment to end sexual and gender-based crimes[11]. A statement declared, “Our collective voice to speak up for the victims, our will to act, our resolve to end the cycle of violence against women, and our commitment to hold perpetrators accountable through a robust and credible judicial process must remain firm and unabated.”[12] Now the ICC moves forward with women leaders at its helm.

President Judge Silvia Alejandra Fernández de Gurmendi

Judge Silvia Alejandra Fernández de Gurmendi was born 24 October 1954 in Argentina. She studied law at the universities of Córdoba and Limoges and earned her doctorate at

President Judge Silvia Alejandra Fernandez de Gurmendi

the University of Buenos Aires. Her first job was with the Argentinian diplomatic service having completed training as a diplomat.

Judge Fernández de Gurmendi has served as a judge on the ICC since 2010 and in 2015 was elected as its President. For over 20 years she has practiced in the areas of international humanitarian law and in human rights. Judge Fernández de Gurmendi represented Argentina before universal and regional human rights bodies and advised on transitional justice issues related to the prevention of genocide and other international crimes.[13] It was while she was serving as director-general for human rights at the foreign ministry that Judge Fernández de Gurmendi joined the preparatory committee at the United Nations headquarters in New York to work on the draft of a statute for the establishment of the ICC.[14]

[1] http://globalgendercurrent.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/cedawlogo.jpg – Picture Source

[2]Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, UN Women (Dec. 31, 2007), http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/.

[3] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women to meet in Geneva from 26 October to 20 November, United Nations Human Rights (Sept. 22, 2015), http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=16629&LangID=E.

[4] Id.

[5]http://www.unwomen.org/~/media/headquarters/images/sections/news/in%20focus/wps%202015/1325_logo_v_blue.jpg?v=1&d=20151009T214552?la=en – Picture Source

[6] OSAGI, Landmark resolution on Women, Peace and Security (Security Council resolution 1325), Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women, http://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/wps/.

[7]Sushma Swaraj Pitches for Expansion of United Nations Security Council, Press Trust of India, Oct. 15, 2015, http://www.ndtv.com/world-news/unsc-favours-doubling-number-of-women-in-peacekeeping-operations-1232356.

[8] Ghana News Source, UN Security Council Resolution 1325 anniversary marked, GhanaWeb (Oct. 9, 2015), http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/regional/UN-Security-Council-Resolution-1325-anniversary-marked-386646.

[9] http://ilg2.org/2015/03/18/four-women-at-the-top-of-the-international-criminal-court-an-international-first/

[10] http://www.unictr.org/sites/unictr.org/files/case-documents/ictr-96-4/appeals-chamber-judgements/en/010601.pdf

[11] https://www.icc-cpi.int/en_menus/icc/press%20and%20media/press%20releases/Pages/pr1093.aspx

[12] Id.

[13] http://councilandcourt.org/the-laguna-workshop/participants/

[14] http://www.irishtimes.com/news/crime-and-law/international-criminal-court-elects-first-woman-president-1.2164183