World Without Genocide and the International Criminal Court

Introduction. The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an international tribunal in The Hague in the Netherlands. It has a unique jurisdiction: to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression.

The ICC is intended to complement countries’ existing legal systems and is to be used only when a country is either unwilling or unable to prosecute criminals or when the UN or individual countries refer specific cases to its jurisdiction.

The ICC has a long legacy, harkening back to the model of the international Nuremberg trials that followed World War II. For the next fifty years, however, there was no permanent court to address the most egregious crimes on the planet.

To address this gap, the United Nations created ad hoc tribunals to prosecute perpetrators of the genocides in Rwanda, former Yugoslavia, Cambodia, and elsewhere, but these courts had no jurisdiction beyond the specific cases of mass atrocities that were the ad hoc courts’ charges.

The ICC came into being in 1998 with the ratification of the Rome Statute, a document that outlines the court’s foundation and procedures. The Court began functioning in 2002 and addresses cases occurring from 2002 forward.

Currently, there are 123 nations that are parties to the Rome Statute, and therefore members of the ICC. The United States is not one of those nations.

Assembly of State Parties. Every year, representatives of the 123 nations that are members of the ICC participate in a two-week administrative meeting called the Assembly of State Parties (ASP). The ASP is held alternately either in The Hague, Netherlands, where the ICC is located, or at United Nations headquarters in New York.

Attendance at ASP includes not only members of the state parties but also representatives of those countries that are not yet members, such as the US, and also non-governmental organizations (NGOs). It is in that context that World Without Genocide is involved.

For the past four years, we have participated with the AMICC delegation, the American NGO Coalition for the ICC. This year, two of our Ferencz Fellows joined Dr. Ellen Kennedy for the meetings. Sarah Erickson, J.D., served as the delegation’s Deputy Convener. She and Helena Sung, third-year student at Mitchell Hamline School of Law, attended key meetings and prepared reports that will be distributed to NGO leaders throughout the US.

ASP issues included victims’ rights; gender issues in justice; budgetary and procedural decisions; election of new judges; and much more. Our two rapporteurs have written blog posts about issues that were particularly important to them, and we invite you to read their remarks below. Please share comments with us at admin@worldwithoutgenocide.org

Helena Sung, Ellen Kennedy, and Sarah Erickson at the Assembly of State Parties, 2017, held at the United Nations, New York.

Role of Victims in the Fight against Impunity

Helena Sung

Benjamin B. Ferencz Fellow in Human Rights and Law

World Without Genocide

Victims play a central part in the International Criminal Court (ICC). When the Court was formed, the Rome Statute, which specifies the ICC’s procedures, gives victims the right to participate in trials and establishes victims’ rights to seek and receive reparations, which include both monetary compensation and rehabilitation. The first side event during the 16th session of the Assembly State Parties (ASP), titled “Victims’ Reflections on Reparative Justice – the Voice and Role of Victims on the Fight Against Impunity for Core Crimes Under International Law,” highlighted the importance of victims from various perspectives.

A Darfuri victim recounted his experience as a survivor and refugee. Before the attack on his village in Darfur, Mohmed was a volunteer teacher. When the attack happened, Mohmed lost his brother and was forced to leave his family behind to seek safe refuge. ICC proponents often underscore the ICC’s role to provide justice for victims, and Mohamed emphasized this importance in his testimony. He stated that the ICC is the only hope for justice for victims and survivors just like him, and this is why he participates in the ICC proceedings.

Joseph Akwenyu Manoba is a legal victim representative. He, too, emphasized that victims view the ICC as the only credible option for justice. He said that victims aren’t able to trust the local justice system. Mr. Manoba further highlighted that local civil societies and victim advocates have faith in the ICC, and they share this belief with the victims. Legal representatives and victim advocates are often the first contact that a victim has before any ICC proceedings begin. The lerepresentatives and advocates become the bridge between the ICC and the victims. Because of the trust built from these relationships with the victims, the legal representatives and advocates become invaluable partners of the ICC institution.

The ICC was created with the foresight of reparative justice for victims. Although the trauma and damage of the atrocities can never be fully repaired and restored, the ICC works to that end. The panel ended with a reminder by Dr. Yael Danieli that reparative justice is not an endpoint but a process by which victims need to be treated with dignity and respect. A continued commitment for reparative justice is needed to make it a reality for victims.

Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice

Sarah Erickson, J.D.

Benjamin B. Ferencz Fellow in Human Rights and Law

World Without Genocide

Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice is an international organization working to bring justice for women and communities affected by armed conflict. Gender Justice has played an integral role in creating and maintaining an independent and effective International Criminal Court since the Court’s inception. Its Executive Director, Brigid Inder, served as Special Advisor on Gender to Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensounda, helping the Prosecutor implement policies aimed at reaching gender equity at all levels and in all areas of the Court’s functions

Gender Justice staff documents incidents of sexual and gender-based crimes and publishes reports based on the data. The latest publication, The Compendium, is an analysis of the Court’s cases: each of the twenty-five cases that the Court has prosecuted, all cases currently in process, and each of the preliminary examinations. The analysis examines each in turn, notes the status of the case and any gender-based crimes charges, and provides implications of these charges in short descriptions and easy- to-comprehend charts.

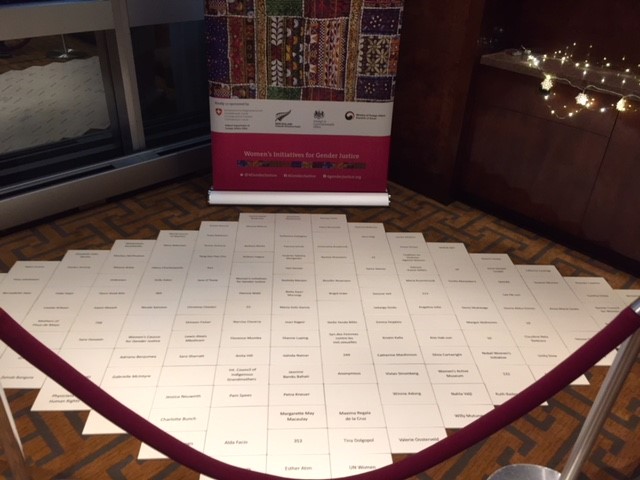

At this year’s Assembly of State Parties, the Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice launched the Legacy Wall, pictured right. This wall is a living memorial made up of individual tiles that create a mosaic commemorating people who have worked and continue to work tirelessly to advance global gender justice. As global justice continues to progress, the wall will grow to include the next generations of human rights leaders. The Legacy Wall will be installed later this year at the ICC’s permanent location in The Hague, Netherlands.

Honorees include human rights giants Angelina Jolie, Navi Pillay, United States Supreme Court Justice Ruther Bader Ginsberg, International Criminal Court Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, and Nuremburg prosecutor and lifelong ICC advocate Benjamin Ferencz. The honorees also include individuals whose names we will never know: courageous men and women who are known only by witness numbers that were assigned to them when they testified against heinous perpetrators of sexual and gender-based crimes.

I am humbled and inspired by these brave people who are standing up to protect those who are the most vulnerable.

Personal Reflection: Making Reparative Justice into Reality

Helena Sung

Benjamin B. Ferencz Fellow in Human Rights and Law

World Without Genocide

I had dreamed of attending the 16th Assembly of State Parties of the International Court. The reason is that the ICC includes victims as part of the international legal framework, which I feel is critical to justice. I wanted to witness and learn firsthand the progress and challenges faced by implementing the reparative justice framework.

The ICC has demonstrated its commitment to victims by the large number of victims participating in trials and the recent development of reparation mandates ordered by the Court. As of September 2017, over 12, 985 victims have participated in proceedings before the Court. The Court also expects that an additional 7,400 victims will apply for participation and reparations in 2018.

Despite the ICC’s encouraging progress with victim involvement, however, there are also continued challenges. One of those challenges is the lack of a clear legal aid system to ensure victims’ choice of legal representation. A second challenge is that the Trust Fund for Victims, tha fund of voluntary contributions for victims’ reparative justice, has decreased sharply. The Fund is supported solely through these voluntary gifts The grave need for an improved victim legal representation infrastructure and the dire need for state parties to increase their donations to the Fund demonstrate the difficulties of making reparative justice a reality. On the other hand, state parties, victims, and victims’ advocates all expressed a dedication to making reparative justice a true reality. One recommendation is to link contributions to reparative justice to the particular country where that justice is most needed, and to have countries support these efforts at greater levels for their own nations.

Although the US is not involved as a state party, we can draw important lessons about reparative justice from the ICC efforts. For example, there are specialty courts across the US based on the concept of restorative justice, a unique effort in our justice system that is almost completely based on retributive justice, or punishment.

Personal Commentary on the Assembly of States Parties, 2017

Sarah Erickson, J.D.

Benjamin B. Ferencz Fellow in Human Rights and Law

World Without Genocide

I have attended the Assembly of States Parties to the International Criminal Court, or ASP, for the past three years on behalf of World Without Genocide. For the first two years, the meeting was held in The Hague, Netherlands at a major conference center called The World Forum. This year the meeting was at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

The difference between the two venues was noticeable. The politics that come in to play during meetings of the UN seemed to carry over into ASP in terms of more formality and fewer opportunities for connecting with people from other countries.

Although the meeting is an ‘assembly of states parties,’ meaning that it is a gathering of representatives of the 123 nations that have ratified the Court’s Rome Statute, members of civil society are allowed and, indeed, encouraged to attend as well. People from NGOs, journalists, aid workers, researchers, and others come from all over the world to share their experiences, with a hope and a belief that the Court will make a difference in seeking justice for targeted people everywhere.

The official ASP delegates negotiated some very important issues this year. They elected new judges, passed the operating budget, and concluded the long-awaited activation of the Court’s jurisdiction over the crime of aggression. However, much of this negotiation happened behind closed doors and without the input of NGOs and other civil society members. I have become very engaged in these issues over the past years, especially the prospect of the Court announcing the activation of the crime of aggression. it was disappointing that I couldn’t attend these important discussions.

This unusual structure had a very positive outcome. Members of NGOs, unable to attend delegates-only meetings, gathered together in the hallways, and conversations occurred between people who might otherwise would not have met. Even if official delegates did not always find mutual ground, their civil society representatives were often able to do so. The previous two years’ ASP meetings may have been easier to navigate, both physically and politically, but this year I saw civil society members from nations with opposing politics state their positions unapologetically and find a way to overcome significant differences.

For the third consecutive year, I came away inspired, re-invigorated to continue advocating for United States participation in the ICC, and proud to be able to advocate for the only court in the world that holds individuals accountable for the gravest of crimes.