A team from World Without Genocide traveled to Burma (Myanmar) in October to explore human rights issues following recent elections. The participants were Jack Rendler, Chair, Board of Directors of World Without Genocide, and two Ferencz Fellows in Human Rights and Law: Jessica Grady and Victoria Dutcher. They prepared the following report.

—————-

We arrived in Yangon on October 18 for two weeks of meetings with representatives of government bodies, non-profit organizations and local human rights advocates. Our goals were twofold: to learn more about the current political, economic, and social climate in Myanmar, and to initiate a relationship between Yangon University School of Law and Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul.

We met with Mr. U Nunt Swe of the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission. The Commission, created by presidential order, is charged with the “promotion and protection of human rights.” The Commission has five divisions: legal, education, promotion, protection, and international relations. The legal division focuses on bringing Myanmar into compliance with international law and making recommendations to the Myanmar government on signing and ratifying human rights treaties. The education department promotes public education about human rights. The promotional division works with local nonprofits to organize events, including a Human Rights Day. Finally, the protection division fields complaints, conducts investigations, and makes findings and recommendations about critical human rights issues.

We received their 2014 annual report and a Burmese-language copy of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Currently, the Commission, recently established in 2011, is emphasizing human rights education in towns and villages outside city centers. Many Burmese people do not understand basic concepts of human rights, and without fundamental education, people are unable to claim their rights or identify and report violations. In 2014, the Commission held 22 human rights talks in various states, drawing 150-350 people for each discussion. The Commission is strengthening its local power, capacity, and institutional identity through this work.

We met with Dr. Khin Mar Yee, Dean of Yangon University Law School, and several professors in the department. The law school offers both a BA and a master’s degree in law and a doctoral program. Within the doctoral program, students can study various areas of law: business, international, maritime, or intellectual property.

The law school has relationships with schools in France, England, Japan, Singapore, and with Columbia University in the US. We discussed an exchange program between students and faculty at Mitchell Hamline and Yangon University. Dr. Yee opined that such a relationship was possible given the recent change in government in Myanmar. With the election of Aung San Suu Kyi, Dr. Yee believes that there has been a decrease in bribery and corruption within the judiciary, and law schools play a significant role in monitoring and promoting ethical legal behavior.

We had informal meetings at Yangon University as well. We spoke to several lecturers in the law department, observed classes, and met with students. Through these conversations we had the opportunity to discuss the differences in earning a law degree in Myanmar versus the United States and learned about areas of law that are specific to southeast Asia.

We spoke to Eh Thaw of the Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG). KHRG focuses on issues that are facing the Karen, an ethnic minority in several countries. KHRG also published a summary of the situation women face in southeastern Myanmar. During ethnic riots and before the ceasefire in 2012, many men fled their villages to seek shelter in neighboring jungles. In their absence, women assumed leadership roles in their villages. Now, with the men returning home and reclaiming their positions of power, women are again relegated to subservience after a period of liberation. The dynamics of these changing roles has caused many problems. KHRG is working on educating and empowering women through workshops in rural villages.

In addition to the many social and political changes occurring in the country, President Obama lifted long-standing economic sanctions against Myanmar. This means that American businesses and individuals can now invest in Myanmar in ways that were previously prohibited. Although this may bring wealth to Myanmar, KHRG fears this will lead to “too much too fast.” In other words, mining and land development companies will likely come into Myanmar and pump money into the economy without examining the social or environmental impact of their actions. Only time will tell if these fears will come true.

We met with Jaime Casanova, an attorney at DFDL Yangon and a member of the American Chamber of Commerce, to talk about economic issues. Mr. Casanova believed that the lifting of economic sanctions represents several great changes in Myanmar. First, Myanmar recently acceded to the New York Convention. This means that foreign arbitration awards must be recognized in Myanmar. In other words, if private parties agree to an arbitration award in another jurisdiction, Myanmar must now recognize and enforce that award even though it was reached in another jurisdiction. This is a promising advancement because international arbitration is increasingly common as a form of alternative dispute resolution. Myanmar can participate in international commercial transactions and be bound by the same regulations as its trade partners. Mr. Casanova hoped that Myanmar would appoint someone within the high courts to monitor implementation in the long run. Second, Myanmar recently passed a new foreign investment law to lessen the challenges to foreign investors. Foreign investors can now carry out business in Myanmar as a wholly foreign-owned business. Previously, foreign investors had to create a joint venture with a Myanmar business. Joint ventures have been daunting to foreign investors because Myanmar still has many bureaucratic roadblocks to registering a joint venture. Therefore, the possibility of investing in Myanmar as a wholly foreign-owned business is more attractive.

Mr. Casanova pointed out several areas where significant change must occur. Myanmar must update the infrastructure, including building roads and expanding electricity and internet capabilities, because those systems are outdated and not capable of supporting an increasingly open and growing economy. As more tourists and businesspeople visit Myanmar, the country must be able to support their pursuits. The country’s intellectual property laws also need to be updated and more comprehensive to attract outside investors. For example, Myanmar intellectual property law does not cover patents, only trademarks and copyrights, and even they are only minimally protected. Without intellectual property law that also covers patents, investors may fear local partners will steal their trade secrets or patent information and then abandon the partnership.

Overall, Mr. Casanova sees opportunities for business growth in the wake of the ending of sanctions; he also predicts significant business growth if appropriate infrastructure and legal development can occur fairly soon.

We attended a meeting of the Rotary Club of Yangon. The Club is made up of mostly of Burmese businesspeople and Thai financiers who regularly commute between Myanmar and Thailand. At the meeting, Mr. Hezi Bilik of the Israeli Water Authority gave a presentation on water conservation. He spoke about the economic benefits of an improved water supply that far outweigh the investment costs. Currently, Myanmar has intense rainy seasons, yet the ability to conserve and purify water is weak. Although most city-dwellers have access to indoor plumbing and sanitary water, those who live in rural areas commonly depend on wells and do not treat their water. Rotarians hope that some of Israel’s programs and educational campaigns regarding water issues can be replicated successfully in Myanmar.

We met with Huibert Oldenhuis at Nonviolent Peace Force (NP). NP is an international nonprofit organization that focuses on monitoring ceasefires set in place following conflict. The Myanmar chapter is unique in that it does not have any employees on the ground. Instead, NP partners with local organizations to coordinate 400 volunteers for on-the-ground monitoring and violations of ceasefire agreements between various ethnic groups and government forces. NP staff also work to raise awareness about ceasefires and to educate about the importance of maintaining peace.

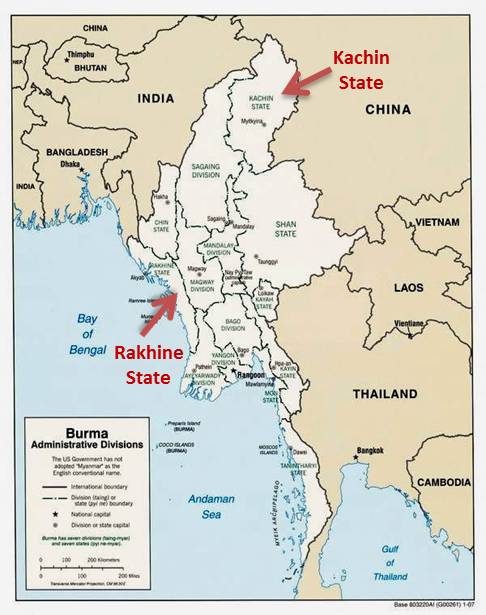

Mr. Oldenhuis talked about the Rohingya, a persecuted Muslim minority located largely in Rakhine state in western Myanmar. NP does not have a presence in Rakhine state; humanitarian aid and access for human rights groups have been cut off. There are conflicting reports about whether the Rohingya have taken up arms in frustration. Mr. Oldenhuis believes the Buddhists within Rakhine state feel targeted because they are wrongly portrayed as the “bad guys.” The international community largely focuses on religious differences between the Muslim Rohingya and the majority Buddhists when there is so much more at play, including unequal resource distribution. Mr. Oldehuis stated that the heightened religious rhetoric only plays into the Buddhist hardliners’ agenda because the Rohingya are reticent to call attention to themselves and to identify collectively as Muslims. Mr. Oldenhuis cautioned against an overly-Westernized interpretation or religion-centric approach to the ethnic conflict that is exploding in Myanmar.

Ryan Casselberry, a political officer at the U.S. Embassy in Yangon, focuses on issues in Rakhine state. He spoke with us about recent contentious events in Rakhine state including recent murders when assailants stole weapons and killed several security officers. Reports immediately blamed the attacks on the Rohingya. Media linked the attack to ISIS, which has poor implications for the perception of the Rohingya in Rakhine state.

Despite the fact that the Rohingya are uniquely disadvantaged, Mr. Casselberry suggested a more balanced approach. He cautions that it is not only the Rohingya who are suffering in Rakhine state. There is no infrastructure, no education, no health care, no financing, and there is major food insecurity throughout the state. Others in Rakhine state feel ignored in light of all the public attention given to the situation of the Rohingya. Many outside of Rakhine state feel equally ignored. For example, humanitarian aid to the Kachin state has been cut off for more than three months, yet this has merited little international attention. Therefore, Mr. Casselberry emphasized that perspective is critical to understanding the political climate in Myanmar. Shrill international voices should not drown out local, moderate ones. Instead, Mr. Casselberry advocated for international actors to ensure they are seeking out and presenting a balanced narrative when discussing the current situation in Myanmar, rather than solely focusing on the plight of the Rohingya to the exclusion of other ethnic groups.

We had an opportunity to meet Robert San Aung, a human rights attorney in Yangon and former political prisoner. He has been jailed six times, and since his most recent release he has worked tirelessly to defend other political prisoners. Although the recent government change is promising, he opined that there is much to be done because many judges are still biased against political dissidents. He would like to see judicial term limits and he would institute judicial monitoring. He also said education will be important under this new government. Echoing the sentiments expressed by Mr. Swe at the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission, he, too, stated that Burmese people do not understand what human rights are and they tend to use the term too broadly, which weakens its power. Finally, he expressed a desire for increased legislative lobbying to change old-fashioned libel laws and to stop the use of torture in national prisons. Being in his presence was both educational and humbling.

We spoke with Naw Ohn Hla, the co-founder of Democracy and Peace Women Network (DPWN), which focuses on education and employment for women and land rights. She works with farmers whose land has been usurped by the military or the government and uses the court system to assert the farmers’ rights over their land. She hopes to bring more attention to the land-grabbing problem, particularly where it overlaps with women’s rights. Although many women own their own land, they are not able to assert property rights solely because they are women. By advocating for women while also advocating for an end to land grabbing, Ms. Hla pushsz for both political and social change.

In conclusion, Myanmar is a country of undergoing significant growth and change, poised to enter the international economic arena. At the same time, many rural Burmese face problems in accessing sanitary water, asserting their basic human rights, and promoting gender equality. The democratic election of Aung San Su Kyi is a promising development, but much needs to change within the government and the judiciary before the vestiges of military rule are truly removed. Myanmar is already a different country than it was when representatives from World Without Genocide visited in January 2016, with positive changes in human rights, economic development, and openness.

Leave a Comment